Acute respiratory distress syndrome: Study IDs surgical patients at risk

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a leading cause of respiratory failure after surgery. Patients who develop the lung disorder postoperatively are at higher risk of dying in the hospital, and those who survive the syndrome may still bear its physical effects years later. A Mayo Clinic-led study is helping physicians better identify patients most at risk, the first step toward preventing this dangerous and costly surgical complication. They found nine independent risk factors, including sepsis, high-risk aortic vascular surgery, high-risk cardiac surgery, emergency surgery, cirrhosis of the liver, and admission to the hospital from a location other than home, such as a nursing home.

The findings are published in the journal Anesthesiology.

“This is a very common reason for needing an extended course of breathing support after surgery, and approximately 20 to 25 percent of patients who develop the syndrome will die from it,” says first author Daryl Kor, M.D., a Mayo Clinic anesthesiologist. “It’s well-documented that those who develop this syndrome stay in intensive care longer and in the hospital longer, and the impact of the syndrome can persist for many years.”

Prevention of acute respiratory distress syndrome has become a priority for the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the researchers noted.

To help prevent the condition, physicians first must identify who is most at risk, and that has proved difficult to do with individual patients, the researchers say. They studied 1,562 surgical patients considered at high risk of developing the syndrome, and found:

Acute respiratory distress syndrome developed in 117, or 7.5 percent.

Nine independent factors are predictors of the syndrome: sepsis; high-risk aortic vascular surgery; high-risk cardiac surgery; emergency surgery; cirrhosis; admission to the hospital unit from a location other than home, such as a nursing home or another hospital; increased respiratory rate; and two measurements that indicate hypoxemia, a lower-than-normal oxygen level in the blood.

Identifying those nine risk factors for surgical patients allowed researchers to refine previous risk prediction models; the new model can be used to identify high-risk patients before surgery for possible participation in acute respiratory distress syndrome prevention studies.

The findings may alter the way patients at high risk of the syndrome are cared for in the operating room, Dr. Kor says.

The findings may alter the way patients at high risk of the syndrome are cared for in the operating room, Dr. Kor says.

“For example, we may be a bit more conservative in the way we transfuse blood products. We may also ventilate their lungs in a little different way than we might if their risk score was low,” Dr. Kor says. “We also hope that by identifying these high-risk patients, we might be able to better select a study population for future studies that look at specific prevention strategies. Before, such studies really weren’t feasible because we couldn’t identify high-risk groups with any degree of accuracy.”

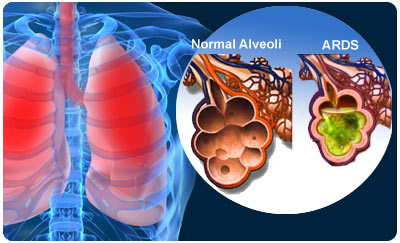

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the sudden failure of the respiratory (breathing) system. It can develop in anyone over the age of 1 who is critically ill. A person with ARDS has rapid breathing, difficulty getting enough air into the lungs and low blood oxygen levels.

ARDS usually develops in people who are already very ill with another disease or who have major injuries. They are usually already in the hospital when they develop the ARDS.

ARDS can be life-threatening because your body’s organs need oxygen-rich blood to function well. The good news is that because of improved treatment in recent years, more people are surviving ARDS.

If you have ARDS your lung function is likely to return to normal or near normal within several months. But some people with ARDS have lasting damage to their lungs or to areas outside the lungs.

Future research may include studying the specific role that anesthetic care plays and whether aspects of care in the operating room should be modified in patients at high risk of developing the syndrome, Dr. Kor says.

Multiple risk factors exist for ARDS. Approximately 20% of patients with ARDS have no identified risk factor. ARDS risk factors include direct lung injury (most commonly, aspiration of gastric contents), systemic illnesses, and injuries. The most common risk factor for ARDS is sepsis.

Given the number of adult studies, major risk factors associated with the development of ARDS include the following:

Bacteremia

Sepsis

Trauma, with or without pulmonary contusion

Fractures, particularly multiple fractures and long bone fractures

Burns

Massive transfusion

Pneumonia

Aspiration

Drug overdose

Near drowning

Postperfusion injury after cardiopulmonary bypass

Pancreatitis

Fat embolism

General risk factors for ARDS have not been prospectively studied using the 1994 EACC criteria. However, several factors appear to increase the risk of ARDS after an inciting event, including advanced age, female sex (noted only in trauma cases), cigarette smoking, and alcohol use. For any underlying cause, increasingly severe illness as predicted by a severity scoring system such as the Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) increases the risk of development of ARDS.

Genetic factors

A study by Glavan et al examined the association between genetic variations in the FAS gene and ALI susceptibility. The study identified associations between four single nucleotide polymorphisms and increased ALI susceptibility. Further studies are needed to examine the role of FAS in ALI.

###

Study co-authors included physicians and researchers from Mayo Clinic in Rochester and Jacksonville, Fla., and from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Duke University Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, University of Michigan School of Medicine and St. Joseph Mercy Hospital. The NIH-funded United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group collaborated on the study.

The study was supported by a career development grant from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research in Rochester; by National Institutes of Health grants U01-HL108712-01, UL1 TR000135 and KL2 TR000136; and by the Mayo Clinic Critical Care Research Committee.

About Mayo Clinic

Recognizing 150 years of serving humanity in 2014, Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit worldwide leader in medical care, research and education for people from all walks of life.

###

Sharon Theimer

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

507-284-5005

Mayo Clinic