Clinical Examination of the Anorectum

An accurate examination of the anorectum is required in the setting of symptoms referred to that region and should be part of a patient’s routine physical examination (1). Care should be taken to maintain the patient’s dignity and to minimize any embarrassment. The rectal examination is performed with the patient lying in the left lateral decubitus position with knees bent toward the chest. Proper draping is required to expose only the perineum, and good lighting is essential for a careful inspection to exclude obvious abnormalities of the anal and perianal area. Inspection is performed with proper retraction of the buttocks. The buttocks, sacrococcygeal region, vulva or base of the scrotum, and upper thighs should be examined first and then the anal and perianal area.

The next component of the examination involves palpation whereby the gloved and lubricated index finger is used to identify tenderness, mass lesions, and areas of induration and to examine the sacrococcygeal, perineal, and perianal tissues (2).

A fistula tract may be traced and pus may be expressed from the secondary opening. The gloved finger is placed at the anal orifice and gradually inserted into the anal canal where the intersphincteric groove is palpable circumferentially and abscesses or tenderness can be identified. Internal hemorrhoids are often not palpable unless they have formed a thrombosis.

Attention is then focused on the posterior rectal wall above the anorectal ring to identify palpable rectal masses, ulcerated tumors, pedunculated polyps, and abscesses or submucosal rectal masses. Stool in the rectum is deformable but masses are not—they are often fixed, superficially mobile, or tethered. The anorectal ring is prominent in the lateral and posterior region; after the patient is instructed to contract the rectal muscle, the strength of contraction is noted to identify any underlying sphincter injuries.

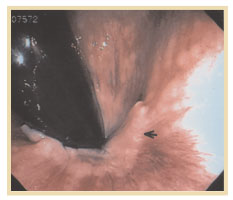

To examine the anal canal or mucosa, anoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is sometimes used. The anoscope is about 7 cm long and 2 cm in diameter with a beveled tip. After insertion into the anal canal, it is withdrawn to the dentate line where the papillae and crypts are inspected and fistula openings and fissures can be identified. The anoscope should not be used as the sole instrument of inspection if there is rectal bleeding. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy performed by a qualified endoscopist can be used to examine the rectum and anorectum on withdrawal and retroflexion (Figure 1).

To examine the anal canal or mucosa, anoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is sometimes used. The anoscope is about 7 cm long and 2 cm in diameter with a beveled tip. After insertion into the anal canal, it is withdrawn to the dentate line where the papillae and crypts are inspected and fistula openings and fissures can be identified. The anoscope should not be used as the sole instrument of inspection if there is rectal bleeding. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy performed by a qualified endoscopist can be used to examine the rectum and anorectum on withdrawal and retroflexion (Figure 1).

—-

Figure 1. The demarcation of “white” squamous cell mucosa and the “pink” columnar mucosa is the dentate line (denoted by the arrow).

—-

Deepak V. Gopal, MD, FRCP (C)

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Gastroenterology

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland VA Medical Center

Portland, Oregon

REFERENCES

1. Schrock TR. Examination and diseases of the anorectum. In: Feldman M, Scharschmidt BF, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.

2. Barnett JL. Anorectal diseases. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, et al, eds. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:2083 - 2107.

3. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation: an epidemiological study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:380 - 386.

4. Breen E, Bleday R. Clinical features of hemorrhoids. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

5. Haas PA, Fox TA, Haas G. The pathogenesis of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:442 - 450.

6. Bleday R, Breen E. Treatment of hemorrhoids. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

7. MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatments: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 1997;40:14 - 17.

8. Reis Neto JA, Quilici FA, Cordeiro F, Reis JA. Open versus semi-open hemorrhoidectomy: a random trial. Int Surg. 1992;77:84 - 90.

9. Khubchandani M. Results of Whitehead operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:730 - 732.

10. Breen E, Bleday R. Anal fissures. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

11. Lund JN, Scholefield JH. Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1335 - 1344.

12. Shub HA, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Conservative treatment of anal fissure: an unselected, retrospective, and continuous study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21: 582 - 583.

13. Brisinda G, Maria G, Bentivoglio AR, et al. A comparison of injections of botulinum toxin and topical nitroglycerin ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:65 - 69.

14. Cook TA, Humphreys MM, McC Mortensen NJ. Oral nifedipine reduces resting anal pressure and heals chronic anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1999;86: 1269 - 1273.

15. Lewis TH, Corman ML, Prager ED, Robertson WG. Long-term results of open and closed sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31: 368 - 371.

16. Breen E, Bleday R. Anal abscesses and fistulas. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

17. Nordgren S, Fasth S, Hulten L. Anal fistulas in Crohn's disease: incidence and outcome of surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:214 - 218.

18. Venkatesh KS, Ramanujam P. Fibrin glue application in the treatment of recurrent anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1136 - 1139.

19. Gopal DV, Young C, Katon RM. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome presenting with rectal prolapse, severe mucorrhea, and eroded polypoid hyperplasia: case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:479 - 483.

20. Mackle EJ, Parks TG. The pathogenesis and patho-physiology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;15: 985 - 1001.

21. Gopal DV, Faigel DO. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound - a review of clinical applications. Endoscopic ultrasonography and therapeutic indications. Series #2. Pract Gastroenterol. 2000;24:24 - 34.

22. Robson K, Lembo AJ. Fecal incontinence. Chopra S, La Mont T, eds. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

23. Nostrant TT. Radiation injury. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, et al, eds. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:2611 - 2612.

24. Swaroop VS, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic treatment of chronic radiation proctopathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:36 - 40.

25. Bonis P, Breen E, Bleday R. Approach to the patient with anal pruritus. [UpToDate Clinical Reference on CD-ROM & Online Web site.] December 2001.

26. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott; 1992:75 - 79.

27. Magdeburg B, Fried M, Meyenberger C. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of anal carcinomas. Endoscopy. 1999;31:359 - 364.