Developing Food Safety Measures

Over time, as the food supply was transferred more and more from local farm families into the hands of food producers and merchants, more opportunities for accidental or intentional contamination arose. In nineteenth-century England, beer, wine, bread, and other foods were routinely adulterated with cheaper ingredients by their makers. Usually, the intent was merely to substitute a cheaper product so the merchant could make a bigger profit, but some of the substituted ingredients had unhealthy side effects.

Dairy cows that provided milk for the early residents of New York City were fed such a meager diet that their milk took on a bluish color, and it was delivered to local neighborhoods by the same trucks that carted away the cow manure. People began to give more thought to their food purchases and demanded action from public officials to assure the safety and purity of their food.

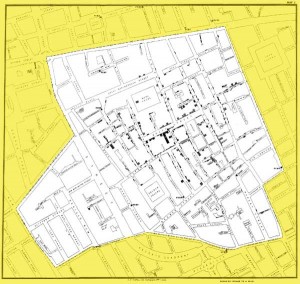

Advances in science during the 1800s and early 1900s awoke people to the fact that many of the illnesses from which they suffered could be traced to their food and drink. John Snow, a London physician, became suspicious when he noted that patients who were suffering from an 1854 cholera outbreak were concentrated in a single neighborhood. He drew up elaborate maps showing exactly where they lived and eventually traced the cause of the outbreak to water from a single contaminated well that supplied all of their houses. Snow’s investigation is regarded as the beginning of epidemiology, the study of the factors that cause illnesses in populations. Years later, scientists working in the new field of microbiology identified the organism that caused cholera, along with causative agents for other waterborne and foodborne illnesses.

From 1902 to 1907, the attention of the American public was riveted on the eating habits of 12 young men who came to be known as the “Poison Squad.” A popular song was even written about them and what they ate. These young men volunteered to eat their meals in the basement of the U.S. government’s Bureau of Chemistry in Washington, D.C. Scientists observed the men for changes in their health and digestion after they dined on meals spiked with various food additives. The experiments were authorized by Congress and duly reported in newspapers and scientific publications of the day. While some might question the scientific value of these early experiments in food safety, there is no question about their impact on the American public. This period also saw the publication of e Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s famous novel that exposed the horrible unsanitary conditions within the Chicago meatpacking industry.

FIGURE 1.4 This map, made in 1854 by Dr. John Snow, highlights deaths from cholera (each one represented by a black dash) and nearby water pumps, which were suspected to be contaminated, in a London neighborhood.

The resulting clamor from the public finally resulted in passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the first major U.S. regulation of the food industry, and a companion act, the Meat Inspection Act.

These acts did much more than impose regulations on food. They also changed the mind-set of the country about the responsibility of government to keep our food safe and set in motion a public interest in the issue that continues to this day.

TYPHOID MARY: AN INNOCENT CARRIER OF DISEASE?

When Irish immigrant Mary Mallon first encountered the public health system of New York City, she greeted a visiting health official with harsh words and a meat fork in her hand. One can only wonder what this hard-working woman understood of the official’s accusations that she had caused the illness of dozens of people. Mallon had immigrated to the United States as a teenager and worked her way up to the desirable position of household cook for several prominent families. By her own account, she had never been sick a day in her life, so the suggestion that she had passed on a serious disease to others must have seemed outlandish to her. Yet the historical facts indicate that she was indeed a silent carrier of the bacteria that cause typhoid, and that the disease was accidentally spread to household members by bacteria passed from her feces and, by way of her hands, into meals that she prepared.