AML Score That Combines Genetic and Epigenetic Changes Might Help Guide Therapy

Currently, doctors use chromosome markers and gene mutations to determine the best treatment for a patient with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). But a new study suggests that a score based on seven mutated genes and the epigenetic changes that the researchers discovered were present might help guide treatment by identifying novel subsets of patients.

The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, come from a study led by researchers at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC - James).

The epigenetic change used in the study is DNA methylation. It involves the addition of methyl groups to DNA, which can reduce or silence a gene’s activity, or expression. Abnormal DNA methylation alters normal gene expression and often plays an important role in cancer development.

Overall, the findings suggest that patients with a low score - indicating that one or none of the seven genes is overexpressed in AML cells - had the best outcomes, and that patients with high scores - that is, with six or seven genes highly expressed - had the poorest outcomes.

“To date, disease classification and prognostication for AML patients have been based largely on chromosomal and genetic markers,” says principal investigator Clara D. Bloomfield, MD, Distinguished University Professor, Ohio State University Cancer Scholar and Senior Adviser.

Statistics About Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Some people use statistics to try to figure out their chances of getting leukemia. Or they use them to try to figure out their chance of being cured or how long they will survive. However, statistics only show what happens to large groups of people. Because no two people are alike, you can’t use statistics to predict what might happen to you.

These statistics about leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are from the American Cancer Society:

About 47,150 people will be told they have leukemia in 2012.

About 13,780 people will be diagnosed with AML this year. Most of those people will be adults.

The average age of a person with AML is about 67.

AML is a little more common in men than in women.

About 10,200 people will die of AML in 2012. Almost all will be adults.

“Epigenetic changes that affect gene expression have not been considered. Here we show that epigenetic changes in previously recognized and prognostically important mutated genes can identify novel patient subgroups, which might better help guide therapy,” says Bloomfield, who is also the William Greenville Pace III Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at Ohio State.

“Epigenetic changes that affect gene expression have not been considered. Here we show that epigenetic changes in previously recognized and prognostically important mutated genes can identify novel patient subgroups, which might better help guide therapy,” says Bloomfield, who is also the William Greenville Pace III Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at Ohio State.

Currently, treatments for adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are determined mainly using the chromosome changes and gene mutations present in AML cells.

In this study, researchers developed a seven-gene scoring system for AML cells that is based on gene mutations and a second type of gene modification called an epigenetic change.

The findings suggest that this scoring system can help doctors determine the best treatment for AML patients.

The seven-gene panel was identified in 134 patients aged 60 and older with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (CN-AML) who had been treated on Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)/Alliance clinical trials.

The researchers computed a score based on the number of genes in the panel that were highly expressed in patients’ AML cells, and retrospectively tested the score in two groups of older patients (age 60 and up) and two groups of younger patients (age 59 and under).

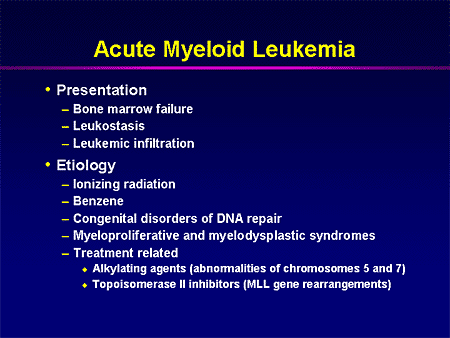

What Is Acute Myeloid Leukemia?

Acute myeloid leukemia starts in the bone marrow. This is the soft inner parts of bones. With acute types of leukemia such as AML, bone marrow cells don’t mature the way they’re supposed to. These immature cells, often called blast cells, just keep building up.

You may hear other names for acute myeloid leukemia. Doctors may call it:

Acute myelocytic leukemia

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Acute granulocytic leukemia

Acute non-lymphocytic leukemia

Without treatment, AML can quickly be fatal. Because it’s “acute,” this type of leukemia can spread quickly to the blood and to other parts of the body such as the following organs:

Lymph nodes

Liver

Spleen

Brain and spinal cord

Testicles

The expected outcome for acute myeloid leukemia depends on certain factors. And of course prognosis is better if your leukemia responds well to treatment. Your outlook is better if:

You are younger than age 60.

You do not have a history of blood disorders or cancers.

You do not have certain gene mutations or chromosome changes.

Patients with a low score - indicating that one or none of the seven genes is overexpressed - had the best outcomes. Patients with high scores - that is, with six or seven genes highly expressed - had the poorest outcomes.

Patients with a low score - indicating that one or none of the seven genes is overexpressed - had the best outcomes. Patients with high scores - that is, with six or seven genes highly expressed - had the poorest outcomes.

“For this seven-gene panel, the fewer highly expressed genes, the better the outcome,” says first author Guido Marcucci, MD, professor of medicine and the associate director for translational research at the OSUCCC – James. “In both younger and older patients, those who had no highly expressed genes, or had one highly expressed gene had the best outcomes.”

Most adults with AML are not cured by current therapies. Only about 40 percent of patients younger than age 60 and about 10 percent of patients 60 and older are alive after three years, so new strategies for treating the disease and for matching the right patient with the right treatment are needed, Bloomfield says.

For this study, Bloomfield, Marcucci and their colleagues used next-generation sequencing to analyze regions of methylated DNA associated with prognostically important gene mutations in CN-AML cells from 134 patients aged 60 and older.

The seven genes identified by the researchers were CD34, RHOC, SCRN1, F2RL1, FAM92A1, MIR155HG and VWA8. For each of these genes, lower expression and higher DNA methylation were associated with better outcome. A summary score was developed based on the number of genes in the panel showing high expression. The researchers validated the score in four sets of patients: older and younger patients with primary AML, and older and younger patients with CN-AML (355 patients total).

When Bloomfield, Marcucci and their collaborators applied the unweighted score to the initial training set of 134 older patients, those with one or no highly expressed genes had a 96 percent complete-remission rate, 32 percent three-year disease-free survival rate and 39 percent three-year overall survival.

Patients with six-to-seven highly expressed genes, on the other hand, had a 25 percent complete-remission rate, a 0 percent three-year disease-free survival rate and 4 percent three-year overall survival.

For younger adult patients, those under age 60, those with one or no highly expressed genes had a 91-100 percent complete-remission rate, a 60-65 percent three-year disease-free survival rate, and a 76-82 percent three-year overall survival. Patients with six-to-seven highly expressed genes, on the other hand, had a 53-71 percent complete-remission rate, a 13-17 percent three-year disease-free survival rate and a 7-24 percent three-year overall survival.

“Overall, our findings suggest that the unweighted-summary score is a better model compared with all other prognostic markers and previously reported gene-expression profiles,” Bloomfield says.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (grants CA101140, CA114725, CA31946, CA33601, CA16058, CA77658, CA129657, CA140158); The Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation; the Deutsche Krebshilfe-Dr. Mildred Scheel Cancer Foundation; the Pelotonia Fellowship Program; and the Conquer Cancer Foundation supported this research.

Other researchers involved in this study were Pearlly Yan, David Frankhouser, Klaus H. Metzeler, Krzysztof Mrózek, Yue-Zhong Wu, Donna Bucci, John P. Curfman, Susan P. Whitman, Ann-Kathrin Eisfeld, Jason H. Mendler, Sebastian Schwind, Heiko Becker, John C. Byrd, Ramiro Garzon, Michael A. Caligiuri, Stefano Volinia and Ralf Bundschuh, The Ohio State University; Kati Maharry, Deedra Nicolet and Jessica Kohlschmidt, Ohio State University and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Statistics and Data Center; Constance Bär and Christoph Plass, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany; Andrew J. Carroll, University of Alabama; Maria R. Baer, University of Maryland; Meir Wetzler, Roswell Park Cancer Institute; Thomas H. Carter, University of Iowa; Bayard L. Powell, Wake Forest University; Jonathan E. Kolitz, Monter Cancer Center; and Richard M. Stone, Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute strives to create a cancer-free world by integrating scientific research with excellence in education and patient-centered care, a strategy that leads to better methods of prevention, detection and treatment. Ohio State is one of only 41 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers and one of only four centers funded by the NCI to conduct both phase I and phase II clinical trials. The NCI recently rated Ohio State’s cancer program as “exceptional,” the highest rating given by NCI survey teams. As the cancer program’s 228-bed adult patient-care component, The James is a “Top Hospital” as named by the Leapfrog Group and one of the top cancer hospitals in the nation as ranked by U.S.News & World Report.

###

Clara D. Bloomfield, MD

Guido Marcucci, MD

The Ohio State University