Scientists discover ethnic differences in immune response to TB bacterium

The immune response to the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB) varies between patients of different ethnic origin, raising important implications for the development of tests to diagnose and monitor treatment for the disease, according to new research published today in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The study, led by researchers at Queen Mary, University of London, in collaboration with the Medical Research Council’s National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR),analysed the immune response of 128 newly-diagnosed TB patients in London who were divided by ethnicity into those of African (45), European (27), Asian (55) or mixed European/Asian (1) ancestry.

TB is an infection caused by the TB bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It commonly affects the lungs. While it grew rare in the UK due to BCG vaccination, improvements in living standards and the introduction of effective antibiotic treatment, it has been on the increase since the late 1980s. TB also remains a major global health problem, responsible for nearly nine million new cases and 1.4million deaths in 2011.

By analysing the levels of various inflammatory markers in blood samples taken before treatment, the scientists showed that immune responses of Asians and Europeans were similar to each other, but different from those of Africans. This difference was caused by ethnic variation in the patients’ genetic make-up and was not related to the strain of TB bacterium that the patients were infected with.

Dr Adrian Martineau, Reader in Respiratory Infection and Immunity at the Blizard Institute, part of Queen Mary, who led the research, said: “The TB bacterium has co-evolved with humans following migration to Europe and Asia some 70,000 years ago, and different strains of the TB bacterium disproportionately infect particular ethnic groups. Experiments with white blood cells cultured in the lab have shown that different strains of the TB bacterium elicit different amounts of inflammation. One might therefore expect that TB patients’ immune responses would differ according to the strain of TB bacterium that they are infected with.

“However our study has shown, for the first time, that it is actually ethnic differences in the patient’s genetic make-up that cause most of this variation in immune responses – with little effect of the TB strain they are infected with.”

Tuberculosis facts

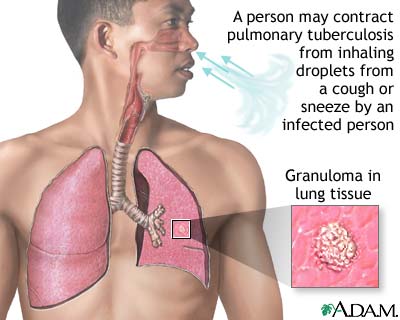

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infection, primarily in the lungs (a pneumonia), caused by bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is spread usually from person to person by breathing infected air during close contact.

TB can remain in an inactive (dormant) state for years without causing symptoms or spreading to other people.

When the immune system of a patient with dormant TB is weakened, the TB can become active (reactivate) and cause infection in the lungs or other parts of the body.

The risk factors for acquiring TB include close-contact situations, alcohol and IV drug abuse, and certain diseases (for example, diabetes, cancer, and HIV) and occupations (for example, health-care workers).

The most common symptoms and signs of TB are fatigue, fever, weight loss, coughing, and night sweats.

The diagnosis of TB involves skin tests, chest X-rays, sputum analysis (smear and culture), and PCR tests to detect the genetic material of the causative bacteria.

Inactive tuberculosis may be treated with an antibiotic, isoniazid (INH), to prevent the TB infection from becoming active.

Active TB is treated, usually successfully, with INH in combination with one or more of several drugs, including rifampin (Rifadin), ethambutol (Myambutol), pyrazinamide, and streptomycin.

Drug-resistant TB is a serious, as yet unsolved, public-health problem, especially in Southeast Asia, the countries of the former Soviet Union, Africa, and in prison populations. Poor patient compliance, lack of detection of resistant strains, and unavailable therapy are key reasons for the development of drug-resistant TB.

The occurrence of HIV has been responsible for an increased frequency of tuberculosis. Control of HIV in the future, however, should substantially decrease the frequency of TB.

By analysing blood samples taken from 85 of the original cohort after an eight-week period of intensive treatment, the researchers found that ethnic variation in immune responses became even more marked. A number of immunological biomarkers, which correlated with either fast or slow clearance of the TB bacteria, were identified and found to differ between Africans and Europeans/Asians.

By analysing blood samples taken from 85 of the original cohort after an eight-week period of intensive treatment, the researchers found that ethnic variation in immune responses became even more marked. A number of immunological biomarkers, which correlated with either fast or slow clearance of the TB bacteria, were identified and found to differ between Africans and Europeans/Asians.

Dr Anna Coussens, who measured immune responses in patient samples at NIMR, said: “These findings have important implications, both for the development of new diagnostic tests, which increasingly rely on analysing the immune response, and also for work to identify candidate biomarkers to measure response to anti-TB treatment. In the future, diagnostic tests and biomarkers will need to be validated in different ethnic populations.”

A key factor in determining the ethnic variation identified in the study appears to be the patients’ genetic type of vitamin D binding protein – a molecule which binds vitamin D in the circulation.

Dr Martineau said: “There are different genetic types of this protein which vary in frequency between ethnic groups, adding to the growing evidence that vitamin D and the way it is carried in the blood is crucial in determining how a patient’s immune system will respond to TB.”

Dr Martineau said: “There are different genetic types of this protein which vary in frequency between ethnic groups, adding to the growing evidence that vitamin D and the way it is carried in the blood is crucial in determining how a patient’s immune system will respond to TB.”

Further studies in other populations are now needed to validate the ethnic difference identified.

This work was funded by the British Lung Foundation and the Medical Research Council (MRC).

Dr John Moore-Gillon, Honorary Medical Adviser at the British Lung Foundation, which co-funded the research, said:

“Targeted therapies have long been talked about as the future of medicine. However, in order to develop such treatments, you first need to understand the ways in which the genetic makeup of different people can affect how a disease develops in, and affects, the body. This new research makes great strides forward in doing this for TB, highlighting for the first time how using different approaches for people of differing ethnic backgrounds can help improve our ability to diagnose the disease and monitor the effectiveness of any subsequent treatment.

“TB is a growing problem in the UK. With TB bacteria being notoriously difficult to identify and eradicate from the body, research such as this, that helps improve diagnosis and treatment of the disease, will be vital if we are to keep on top of the battle against its spread.”

###

Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection. The most common type of TB is in the lungs, known as pulmonary TB. While TB can affect any part of the body, only TB of the lungs or throat is infectious.

Before antibiotics were introduced, TB was a major health problem in the UK. While the condition is much less common now it has gradually increased over the last 20 years, particularly among ethnic minority communities who are originally from places where TB is more common.

In 2011, 8,963 cases of TB were reported in the UK, with more than 6,000 of these cases affecting people who were born outside the UK.

###