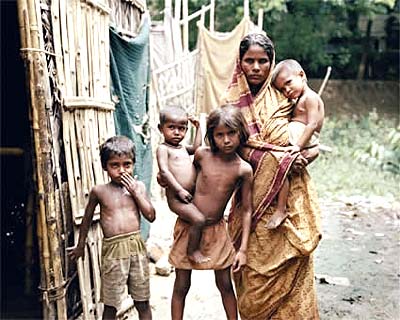

In rural India, children receive wrong treatments for deadly ailments

Few health care providers in rural India know the correct treatments for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia - two leading killers of young children worldwide. But even when they do, they rarely prescribe them properly, according to a new Duke University study.

Medical practitioners typically fail to prescribe lifesaving treatments such as oral rehydration salts (ORS). Instead, they typically prescribe unnecessary antibiotics or other potentially harmful drugs, said Manoj Mohanan, a professor in Duke’s Sanford School of Public Policy, and lead author of the study.

Diarrhea and pneumonia accounted for 24 percent of deaths among children 1 to 4 years old, totaling approximately 2 million deaths worldwide in 2011. Bihar, India - where the study was conducted - has an infant mortality rate of 55 per 1000 live births, the highest in the country.

“The Know-Do Gap in Quality of Health Care for Childhood Diarrhea and Pneumonia in Rural India” will be published online Feb. 16, 2015, by JAMA Pediatrics.

“We know from previous studies that providers in rural settings have little medical training and their knowledge of how to treat these two common and deadly ailments is low,” Mohanan said.

“Eighty percent in our study had no medical degree. But much of India’s rural population receives care from such untrained providers, and very few studies have been able to rigorously measure the gap between what providers know and what they do in practice.”

The study involved 340 health care providers. Researchers conducted “vignette” interviews with providers to assess how they would diagnose and treat a hypothetical case. Later, standardized patients - individuals who portrayed patients presenting the same symptoms as in the interviews - made unannounced visits. This strategy enabled researchers to measure the gap between what providers know and what they actually do - the “know-do” gap.

The study involved 340 health care providers. Researchers conducted “vignette” interviews with providers to assess how they would diagnose and treat a hypothetical case. Later, standardized patients - individuals who portrayed patients presenting the same symptoms as in the interviews - made unannounced visits. This strategy enabled researchers to measure the gap between what providers know and what they actually do - the “know-do” gap.

Providers exhibited low levels of knowledge about both diarrhea and pneumonia during the interviews and performed even worse in practice.

For example, for diarrhea, 72 percent of providers reported they would prescribe oral rehydration salts- a life-saving, low-cost and readily available intervention - but only 17 percent actually did so. Those who did prescribe ORS also added other unnecessary or harmful drugs.

In practice, none of the providers gave the correct treatment: only ORS, with or without zinc, and no other potentially harmful drugs. Instead, almost 72 percent of providers gave antibiotics or potentially harmful treatments without ORS.

“Massive over-prescription of antibiotics is a major contributor to rising antibiotic resistance worldwide,” Mohanan said. “Our ongoing studies aim to understand why providers who know they shouldn’t be prescribing antibiotics for conditions like simple diarrhea continue to do so.

“Massive over-prescription of antibiotics is a major contributor to rising antibiotic resistance worldwide,” Mohanan said. “Our ongoing studies aim to understand why providers who know they shouldn’t be prescribing antibiotics for conditions like simple diarrhea continue to do so.

“It clearly is not demand from patients alone, which is a common explanation, since none of our standardized patients asked for antibiotics but almost all of them got them,” he said.

Providers with formal medical training still had large gaps between what they knew and did, but were significantly less likely to prescribe harmful medical treatments.

“Our results show that in order to reduce child mortality, we need new strategies to improve diagnosis and treatment of these key childhood illnesses,” Mohanan said. “Our evidence on the gap between knowledge and practice suggests that training alone will be insufficient. We need to understand what incentives cause providers to diverge from proper diagnosis and treatment.”

###

Mohanan also holds appointments with the Duke Global Health Institute and the Department of Economics. His co-authors are Marcos Vera-Hernandez and Soledad Giardili of University College London; Veena Das of Johns Hopkins University; Jeremy D. Goldhaber-Fiebert of Stanford University School of Medicine; Tracy L. Rabin and Jeremy I. Schwartz of Yale School of Medicine; Sunil S. Raj of the Indian Institute of Public Health; and Aparna Seth of Sambodhi Research and Communications.

Funding for the study was provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as part of the Bihar Evaluation of Social Franchising and Telemedicine (BEST) project.

CITATION: “The Know-Do Gap in Quality of Health Care for Childhood Diarrhea and Pneumonia in Rural India.” Manoj Mohanan, Marcos Vera-Hernandez, Veena Das, Soledad Giardili, Jeremy D. Goldhaber-Fiebert, Tracy L. Rabin, Sunil S. Raj, Jeremy I. Schwartz, and Aparna Seth. JAMA Pediatrics. Feb. 16, 2015. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3445

###

Karen Kemp

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

919-613-7394

###

Duke University

Journal

JAMA Pediatrics