LASIK for Older Adults

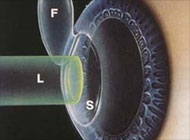

A new University of Illinois at Chicago study appearing in the online edition of the journal Ophthalmology reports on the safety, efficacy and predictability of laser eye surgery (laser in situ keratomileusis or LASIK) in patients 40-69 years old.

“We are seeing an increasing demand for LASIK surgery for older adults, who present special challenges,” said study co-author Dr. Dimitri Azar, Field chair of ophthalmologic research at UIC.

In LASIK surgery, adjustments in correction are routinely made to compensate for the cornea’s strong healing responses in younger patients, Azar said. Increased age has been previously associated with poorer final clarity of vision, as measured on an eye chart (visual acuity).

“We were able to show that fine adjustments in the correction to the cornea in our older patients that compensate for differences in age-related healing resulted in reliable predictability of correction,” said Azar, who is also professor and head of the UIC department of ophthalmology and visual sciences.

The researchers examined the case histories of 710 consecutive laser eye surgeries on 424 patients between 40-69 years old. The LASIK surgeries were performed to correct myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness) and astigmatism. All surgeries were performed by Azar between January 1999 and September 2005.

The cases were divided into three groups based on age: group one, 40-49 years old (359 eyes); group two, 50-59 years old (293 eyes); and group three, 60-63 years old (58 eyes).

Outcomes of the laser surgery corrections were analyzed for near-sightedness with or without astigmatism (511 eyes) and far-sightedness with or without astigmatism (199 eyes). Patients’ outcomes included a follow-up of at least six months and, where possible, 12 months. The study found no difference in safety between the groups.

At the final follow-up of the nearsighted-corrected patients, 86 percent of eyes in group one, 85 percent of group two, and 100 percent of group three had 20/30 or better visual acuity without glasses. In all groups, there was 20/40 or better visual acuity for 91 to 100 percent of patients.

For farsighted patients, 80 to 84 percent of all groups had 20/30 or better visual acuity at final follow-up, with 91 to 97 percent of all groups achieving 20/40 or better uncorrected vision. There was no statistical significant difference in final visual acuity between the different age groups.

Another challenge for older patients is difficulty with near vision after LASIK due to the loss of the ability to accommodate (presbyopia), Azar said. “As we age, we lose some elasticity of the lens of the eyes, making it impossible to maintain a clear image as objects are moved closer,” he said.

Many patients in the study opted for monovision, a strategy that compensates for presbyopia by correcting one eye for distance and the other eye for near vision.

“Patients who understand that monovision is a compromise that does not restore accommodation, but rather compensates for its loss, are most likely to adapt well to monovision,” Azar said.

“Although LASIK presents different challenges in the presbyopic age group, our study showed that for this age group, 40-69 years old, LASIK correction for near-sightedness and far-sightedness has reasonable safety, efficacy and predictability,” he concluded.

Ramon Ghanem and Jose de la Cruz Napoli, UIC ophthalmology and visual sciences, and Faisal Tobaigy and Leonard Ang, Harvard Medical School, also contributed to the study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award (Dr. Azar).

UIC ranks among the nation’s top 50 universities in federal research funding and is Chicago’s largest university with 25,000 students, 12,000 faculty and staff, 15 colleges and the state’s major public medical center. A hallmark of the campus is the Great Cities Commitment, through which UIC faculty, students and staff engage with community, corporate, foundation and government partners in hundreds of programs to improve the quality of life in metropolitan areas around the world.

Audio is available by contacting the source.

Source: University of Illinois at Chicago