New Insights Into Obesity and Smoking Stroke Paradoxes

In the control population, although none of the results were statistically significant, the very obese showed a trend toward worse mortality (HR, 1.20; P = .179).

Dr Aparicio reported that there was no interaction between weight groups and stroke severity or stroke subtype (eg, lacunar) among the stroke patients. Further, among the cases and controls, there was no interaction between weight groups and sex or smoking affecting 10-year mortality, he said.

Interaction for Age

However, there was a significant interaction for age. In stroke patients younger than age 70 years, a higher BMI (25 or more) on 10-year mortality was protective (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.34 - 0.80; P = .003 compared with normal weight), but this was not the case for controls (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 0.94 - 2.48; P = .85).

“This was a good exploratory study,” commented Dr Aparicio. “I would like to now focus back on the stroke cases and look at other more subtle differences between the stroke cases in the different weight groups.”

He stressed that further research is needed to understand how weight affects mortality and whether types of fat and fat distribution play a role in the obesity paradox.

“In the Framingham study, we have a lot of biomarkers and a lot of imaging markers. I would be interested to see how lipid hormones and other circulating biomarkers might be cardioprotective,” he said.

Asked about the causes of death in the various weight groups, Dr Aparicio said these data are being collected. At 10 years, causes of death could be “wide ranging both in controls and in patients.”

Following his presentation, Dr Aparicio elaborated on what might be causing the obesity paradox. He said he and his colleagues have already found no difference in terms of cancer prevalence and will be further investigating cardiovascular morbidity. “I think that’s where some of these answers may lie, particularly in the younger participants,” he said.

Today, about 35% of the US population is obese and by the year 2020, it’s estimated that 75% of the population will be overweight or obese, he said.

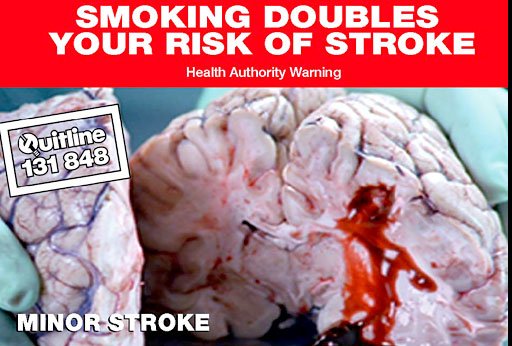

Smoking and Stroke

In a separate presentation, Vishal Jani, MD, interventional neurology fellow, Michigan State University, East Lansing, presented results of a study showing that current or former smokers have a lower adjusted in-hospital mortality from acute ischemic stroke (AIS).

Researchers used information from 2000 to 2011 from a nation-wide inpatient database. They isolated a cohort of patients with AIS using relevant codes, stratified the cohort according to whether they received IV tPA, and then looked at in-hospital mortality among smokers vs nonsmokers.

There were 5,206,102 AIS hospitalizations. Among these, 132,157 (2.6%) patients received tPA.

The in-hospital mortality rate without tPA was 6.36% for nonsmokers compared with 2.83% for smokers (P < .001). The in-hospital mortality rate with tPA was 10.7% for nonsmokers compared with 6.8% for smokers (P < .001).

The in-hospital mortality rate without tPA was 6.36% for nonsmokers compared with 2.83% for smokers (P < .001). The in-hospital mortality rate with tPA was 10.7% for nonsmokers compared with 6.8% for smokers (P < .001).

After adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, primary payer, median household income, hospital region, teaching status, location, and bed size, among other factors, the odds ratio (OR) for the group with IV tPA was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71 - 0.91; P < .001). For the non–IV-tPA group, the adjusted OR was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.60 - 0.64; P < .001).

“It’s interesting that the finding of lower mortality is the same whether they get IV tPA or not,” he commented.

As with obesity, the mechanism of smoking protection is up for debate. Most likely, said Dr Jani, it’s due to the “cumulative effect of reconditioning.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

###

Pauline Anderson

American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 67th Annual Meeting. Abstracts S5.005, S5.006. Presented April 21, 2015.