Poverty, parenting linked to child brain development

Children who grow up in poor families may have smaller brains than their more well-off peers, says a new study. But good parenting may help overcome that disadvantage.

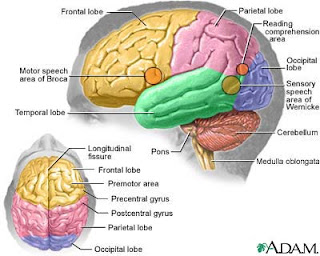

Researchers found that kids who grew up poor tended to have smaller hippocampus and amygdala volumes. Those areas of the brain are partly responsible for regulating memory and emotions.

“Generally speaking, larger brains within a certain range of normal are healthier brains,” Dr. Joan Luby, the study’s lead author, said.

“Having a smaller brain within a certain range of normal is generally not healthy. It’s associated with poorer outcomes,” Luby told Reuters Health. She is a professor of child psychiatry at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Prior studies looking at poverty and brain size found similar patterns. But Luby and her colleagues also wanted to look at what may bring about brain changes.

They found kids tended to have smaller brains when they had experienced stressful life events or when their parents were hostile or unsupportive.

The new findings give parents and researchers a “very specific and changeable” target, Luby said.

The new findings give parents and researchers a “very specific and changeable” target, Luby said.

For their report, published in JAMA Pediatrics, she and her colleagues used data from an existing study of 145 children from in and around St. Louis.

The children were between the ages of six and 12 at the time their brains were imaged. They had been followed since preschool with annual screenings.

The screenings included tests for stress and whether or not the children had entered puberty. At one session, parents and their children were observed together and the researchers assessed parenting styles.

They found children from poor families tended to have smaller brains. But stressful life events and a lack of parental support in family interactions explained some of that link.

The study can’t prove poverty or parenting caused the changes in brain size. But the findings suggest the chance that poor children will have smaller brains may be reduced with supportive parenting, Luby said.

The study can’t prove poverty or parenting caused the changes in brain size. But the findings suggest the chance that poor children will have smaller brains may be reduced with supportive parenting, Luby said.

She added that kids would do best with parents who are sensitive, nurturing, attentive and emotionally available.

“It’s not as if those affluent families are protected from these same (parenting) issues,” Charles Nelson, who wrote an editorial accompanying the new study, said.

“The reason it’s probably more common in poorer families is that they’re lacking in resources and trying to make ends meet.”

“There is a level of background stress … that may keep them from being the parent they want to be,” Nelson told Reuters Health. He is a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital.

Nelson said the findings are limited by the fact that many children in the study were depressed or at high risk of depression. That may influence the results. But he said the new study adds to what is already known about poverty and childhood brain development.

Luby said it will be important to find out what interventions - such as early preschool programs, for instance - may encourage a healthy environment for the developing brain.

“Biology is very much influenced by the environment,” she said. “The question is what period might be the time when the brain is most sensitive to influence.”

SOURCE: JAMA Pediatrics, online October 28, 2013.