Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Breast Cancer > Breast Cancer in the elderly

Breast Cancer and Seniors

When detected early, breast cancer is treated successfully 98% of the time. Researchers continue to make impressive gains in the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer. For example, according to the Mayo Clinic, the radical mastectomy, once a standard procedure for women with breast cancer, is now rarely performed.

However, breast cancer in seniors remains a very potent disease that will only be eradicated if women follow the recommended schedule and undergo annual mammograms. Recent statistics suggest that women are skipping annual mammograms, the key procedure to screening.

The National Cancer Institute estimates that 226,870 women will be diagnosed with and 39,510 women will die of cancer of the breast in 2012. The number of new cases has increased every year for the past thirty years, though death from breast cancer has decreased slightly. Breast cancer remains the second leading cause of cancerous death after lung cancer. It is also the second most common cancer among women after non-melanoma skin cancer.

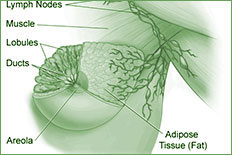

Like all cancers, breast cancer begins with abnormal cell growth. These "bad" cells develop too quickly and spread, or metastasize, throughout the breast, often entering lymph nodes located under the arm or even moving into other parts of the body.

There are several signs of potential breast cancer, including a bloody discharge from or retraction of the nipple; a change in the size or contour of the breast; and a flattening, redness, or pitting of skin over the breast. A lump in the breast remains the most common sign.

If a woman detects a lump, she should see her doctor; however, the Mayo Clinic recommends waiting through one menstrual cycle, as breast shape changes throughout the cycle.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women in the United States, with more than 180,000 reported cases yearly. Despite recent advances, more than 41,000 women per year die of breast cancer in the United States alone. Other than female gender, age is the most important risk factor for the development of breast cancer. In the United States, women aged 65 years or older represent about 13% of the female population but account for nearly 50% of the newly diagnosed breast cancers. More than 60% of breast cancer deaths occur among women over age 65.

Despite the high prevalence of breast cancer among older women and the significant associated morbidity and mortality, researchers have only recently focused on treatment questions in this patient group. Most clinical trials and almost all randomized trials have included few women over age 65. Extrapolation of results of many clinical trials to the geriatric population must be done with caution because of potential differences in tumor biology, host physiology, and problems common among older patients, including comorbidity, impaired functional status, and lack of social support.

This chapter examines the epidemiology, natural history, treatment, and care patterns of breast cancer in the elderly.

Risk Factors

Several primary risk factors are believed to increase the likelihood of breast cancer. However, it's important to keep in mind that most people with one or even several of these risk factors do not get breast cancer.

The Mayo Clinic and National Cancer Institute list these primary risk factors:

- Age

- Chest radiation as a child

- Start of menarche before the age of 12

- Adolescent weight gain

- No pregnancy or late pregnancy (after 30)

- Lengthy use of oral contraceptives

- Post-menopausal weight gain

- Late menopause (after age of 50)

- Increased breast tissue density

Excessive exposure to estrogen, the hormone that promotes the appearance of female secondary sex characteristics, appears to be the leading factor in developing breast cancer. Exposure to a combination of estrogen and progesterone for over a four-year period also increases the risk of breast cancer. This is especially significant due to trends in estrogen therapies to stave off premenopausal syndrome and other maladies. The more recent reduction of hormone replacement therapy has perhaps led to the recent slight decline in breast cancer cases for women over 50. Lehman believes women over 50 should consult their physicians about the apparent risks of hormone replacement therapies, especially if they have a family history of cancer.

Secondary factors, including smoking, obesity, alcohol, family history, diet, and stress, are also significant. As with reducing the risk of all cancers, a healthy lifestyle, including a good diet, frequent exercise, and moderate stress, is recommended.

Genetics may also play a role in breast cancer. Even though less than 10 percent of the breast cancer cases are inherited, women with a family history of the disease have a much greater risk of breast (and ovarian) cancer.

Breast Cancer in Seniors

Eighty percent of all breast cancer occurs in women over 50, and 60 percent are found in women over 65. The chance that a woman will get breast cancer increases from 1-in-233 for a woman in her thirties, to a 1-in-8 chance for a woman in her eighties.

"The average age of diagnosis is 62," says Dr. Julie Gralow, associate professor of medical oncology at the University of Washington School of Medicine and medical oncologist at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. "So the majority of women getting breast cancer are over the age of 50."

Adjuvant endocrine therapies may be offered to patients with endocrine-responsive disease, regardless of age, axillary node involvement, or tumor size. Tamoxifen has historically been one of the most commonly used endocrine therapies, with data supporting a 1- to 5-year course of treatment in elderly patients. Recent results from trials comparing tamoxifen with aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane), given at different time points, reported superior results of the latter over tamoxifen in terms of disease-free survival (DFS). In one of these trials, this also translated into a modest improvement in overall survival (OS), while in another trial longer OS was seen only in node-positive patients and in patients with both estrogen receptor (ER)- and progesterone receptor (PgR)-positive tumors. According to the St. Gallen Consensus Conference, tamoxifen can still be considered an adequate treatment for selected low-risk patients, while for the majority of patients, the introduction of an aromatase inhibitor, either upfront or sequentially after tamoxifen treatment, should be considered.

Adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival for women with early breast cancer. Women aged 50 - 69 years with breast cancer achieve a 20% proportional reduction in the risk for recurrence and an 11% proportional reduction in the risk for death with adjuvant chemotherapy. However, limited data exist on the benefit of chemotherapy in women aged 70 years or older. Very few patients in the oldest age groups have been included in clinical trials to date for several reasons: exclusion criteria for age in some clinical trials; physician (or even patient) bias based on the notion that older patients will not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, will not tolerate it as well as younger patients, or both. In the Early Breast Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) 2005 meta-analysis, as few as 1,529 patients aged >70 years were included, compared with >31,000 patients <70 years, thus failing to show a statistically significant benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in terms of disease recurrence and survival after the age of 70 years. The meta-analysis found a nonstatistically significant 13% reduction in all-cause mortality among women aged 70 years and older who received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Moreover, the small sample size precluded subgroup analysis by hormone receptor status. Despite the small number of patients >70 years old included in the Oxford Overview, the benefits of chemotherapy appear to decline with increasing age. This could also possibly be explained by a shorter life expectancy, a reduction in dose intensity, pathogenetic pathways resulting in reduced chemosensitivity, and the reduced benefit of chemotherapy in endocrine-responsive tumors .

Gralow is especially concerned about the lack of women over 70 years of age in clinical trials.

"There are several situations unique to our older patients. We find it difficult to determine the toxicity levels of chemotherapy," she explains, "because we simply don't have enough information. This is significant because older women tend to have more tumors and thus be more sensitive to estrogen receptor positivity; or they might avoid chemotherapy altogether."

Lack of information is just one of several issues surrounding breast cancer in seniors. An obligation as routine as visiting the doctor can prove challenging if the patient cannot drive or does not have anyone to take her to the appointment. This is quite significant with cancer treatment, as the patient must make six-to-eight weeks of daily trips to the hospital for radiation therapies.

In the U.S., cancer is a disease of aging. The average 65-year-old patient has an anticipated life expectancy of 20 years, and clinicians should take this into account when making breast cancer management decisions. However, older breast cancer patients can present with wide variations in health status, and treatment in older patients should therefore include a careful evaluation of comorbidities, physical function, polypharmacy, and other issues that could potentially impact a patient's ability to undergo chemotherapy without excessive risk.

Evaluation tools are under development, including potential molecular markers, to identify which older patients are the best candidates for chemotherapy, as well as those more susceptible to actually developing cancer. Standard chemotherapy regimens are just as effective in older patients as they are in the younger population, and can substantially prolong life expectancy when used in the right patients. This article discusses breast cancer in seniors, including the epidemiology of breast cancer in these patients, the potential impact of comorbidities, and effective adjuvant therapy in selected older patients.

"Nausea and other side effects are often much more severe with older patients," explains Gralow. "And insurance of oral medicine can be spotty, especially if the patient depends upon Medicare."

Gralow also notes the possible tensions between family involvement and doctor-patient discretion.

"I need to know what the patient wants shared because we need to respect patient privacy while keeping the family informed. So, as with all medicine, we try to bring the patient and her family together for a meeting at the start of the treatment."