Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Carcinoma of the Anus

Carcinoma of the Anus

During the past 30 years, there has been remarkable progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. It is now accepted that anal cancer is a sexually transmitted disease, which can be cured using a combination of chemo- and radiotherapy. The biology of anal cancer remains to be elucidated, as do the molecular mechanisms involved in resistance to chemoradiation. The contribution of HIV infection to tumour progression currently represents an area of intensive investigation. Finally, the growing numbers of AIDS patients who experience prolonged survival represent a population at risk. In the future, cytological screening of male homosexuals with an anal Papanicolaou test may help in identifying high-grade dysplasia and preventing anal cancer.

Carcinoma of the Anus

Introduction

Epidemiology

- Sexual transmission / HPV infection

- Immune suppression / HIV infection

Pathogenesis

Clinical features

Staging

Treatment

Anal canal cancer

Anal margin cancer

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)

References

Introduction

Anal cancer has served during the past two decades as a paradigm for the successful application of chemoradiation to solid tumours. To date, it remains one of the few carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract that are curable without the need for definitive surgery. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that sexually transmitted infection with human papillomavirus is responsible for the majority of cases. This type of neoplasm also provides a good model to study the contribution of immunodeficiency to the development of cancers. In this paper, the anatomy of the anal area is reviewed, the aetiological role of viruses is discussed and the clinical management of patients with anal cancer is presented.

Various definitions of the anal area coexist in the medical literature. In the past this has been the source of considerable confusion. Anal cancer may arise from the anal canal or from the anal margin.

Eighty-five percent of the anal cancers occur in the anal canal and 15% in the anal margin. The anal canal is about 3.5 cm long and extends from the upper to the lower border of the anal sphincter. The anal margin corresponds to a 5-cm area of peri-anal skin, measured form the anal verge. The anal verge is a visible landmark, corresponding to the external margin of the anus, which delineates the junction between the skin epithelium and the hairless and non-pigmented epithelium of the anal canal.

Tumours arising within the anal canal are either keratinising or non-keratinising squamous cell carcinomas, depending on their location below or above the dentate line, respectively. Various terms, such as junctional, basaloid or cloacogenic previously used to describe these tumours ave been abandoned due to the confusion surrounding them. Anal canal carcinomas are characterised by aggressive local growth, including extension to the underlying sphincter muscles. By contrast, cancers originating from the peri-anal skin have a more favourable prognosis and tend to behave more like other skin cancers. Thus, the anal verge is an important anatomical landmark, separating two histologically distinct epithelial structures that give rise to two types of cancers with different natural histories, prognoses and treatment.

Epidemiology

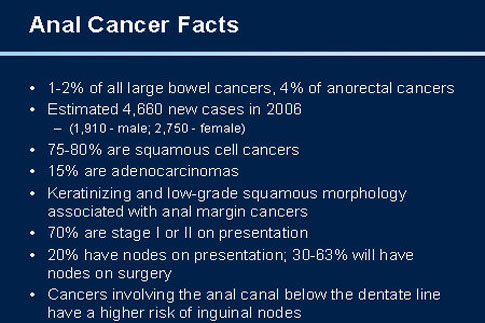

Because of its relatively low incidence, little attention has been paid to squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA) in the past. Carcinomas of the anal canal constitute 1.5% of all digestive system cancers in the United States, with an estimated 3,400 new cases and 500 deaths in 1999 [1, 2].

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

However, the incidence of SCCA (Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus) has markedly increased in younger males during the last three decades. In the San Francisco bay area, the incidence of anal cancer in male homosexuals was 9.9 (95% CI = 4.5-18.7) times higher than expected in 1973-1979 and 10.1 (95% CI = 5.0-18.0) times higher in 1988-1990 [3, 4]. Importantly, this trend was observed even before the AIDS epidemic and some authors consider that the increased risk for SCCA among AIDS patients results from human papillomaviruses (HPV) infection and not from HIV-related immune deficiency [5]. However, the increased incidence of SCAA in renal transplant patients clearly suggests that immunosuppression may play a role in tumour development [6].

Sexual transmission / HPV infection

Population studies from California and Europe have well documented the relation between anal cancer and receptive anal intercourse in individuals of both sexes, irrespective of immunosuppression. A case-control study was conducted in Denmark to compare the contribution of lifestyle to the development of anal vs. rectal cancer [7].

The risk factors associated with anal cancer in women were more than ten sexual partners (RR =2.5), a history of anal warts (RR = 11.7) and anal intercourse before the age of 30 (RR = 3.4). In the same population, HPV DNA was detected by PCR in 88% of the tumours from 394 patients with anal cancer. A cohort study within two large serum banks in Norway and Finland demonstrated an increased risk of developing Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus among subjects seropositive for either HPV 16 (OR = 3.0) or HPV 18 (OR = 4.4) [8]. In addition, there have been numerous reports linking anal cancer and cervical cancer [9]. It appears that the association between cervical cancer and anal cancer is as strong as that between cervical and vulva cancer [10]. Thus, anal cancer is now considered a sexually transmitted disease, which is clinically related to the development of anal warts and infection with HPV oncogenic subtypes 16 and 18.

Carcinoma of the Anus Management

Introduction

Epidemiology

- HIV Infection

- Human Papillomavirus

- Other Causes

Prognostic factors

- Tumor Location and Size

- Lymph Node Involvement

Staging

Disease presentation

Radiation treatment

Combined modality treatment

Optimum chemotherapy regimen

Optimum radiation regimen

Treatment-related toxicities

Follow-Up

Conclusions

References

Immune suppression / HIV infection

Since 1994, numerous epidemiological studies from the United States have demonstrated a high incidence of anal cancer among AIDS individuals [3, 11]. HIV-positive male homosexuals are at increased risk of developing anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) [12, 13]. AIN being a precursor of invasive SCCA (similar to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] and cervical cancer), screening programs using anal Papanicolaou smears in HIV-positive homosexual have been developed and might be cost-effective [14].

Pathogenesis

At the molecular level, the best characterised factor in the development of anal cancer is the integration of HPV DNA into anal canal cell chromosomes [15]. Of note, experimental studies have demonstrated that the presence of high-risk HPV by itself is not sufficient to induce transformation and tumour progression [16]. In immunocompetent individuals, most cases of anogenital HPV infection undergo spontaneous regression. In the case of male homosexuals, it has been possible to investigate the effects of HIV-mediated immune suppression on HPV infection, as dual infection with both viruses is relatively common in this population [17, 18].

HIV positive patients are more likely to have persistent HPV infection, a higher viral load and anal intra-epithelial neoplasia (AIN) than HIV negative patients [19]. Thus, the current consensus is that HIV-related immunosuppression is responsible for an enhanced expression of HPV infection in the anal canal, which may lead to HPV-induced epithelial abnormality [20]. In the emerging model of SCCA progression, two additional factors are implicated in the malignant conversion of HPV-infected epithelial cells of the anal canal, a) the ability to escape cell-mediated immune response and b) the induction of chromosomal instability, reflected by loss of heterozygosity (LOH).

Molecular biology

Studies on squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix have demonstrated that in addition to HPV integration, the neoplastic process requires the loss of tumour suppressor gene (TSG) function, and specific chromosomal aberrations have been detected in cervical and anal squamous carcinomas [21]. Unfortunately, only a few reports on the cytogenetics of SCAA are currently available, and a common underlying theory of pathogenesis has not been established. Most reports include small numbers of patients, and none of them focused on two clinically relevant issues; response to treatment and the role of HIV infection in tumour genesis.

Muleris and colleagues have identified recurrent losses of chromosomes 3p and 11q in a series of 8 tumours [22]. Using comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH), Heselmeyer et al. identified consistent losses mapped to chromosomes arms 4p, 11q, 13q and 17q [23]. It still remains unknown whether these alterations contribute to resistance to current chemoradiation protocols. In addition, the overexpression of P53 protein detected by immunohistochemistry seems to correlate with an inferior outcome in patients who received CRT for SCCA [24, 25]. However, the authors did not correlate the molecular alterations with the HIV status. In another small study, LOH on chromosomes 5p and 18q was detected, demonstrating for the first time mutations of the APC and SMAD4/DCC tumour suppressor genes in SCCA [26]. In summary, the molecular biology of SCCA is far from being elucidated, and thus warrants further investigation. This type of malignancy indeed represents an excellent model in which to study 1) the impact of HIV infection on tumour progression and 2) the role of LOH on response to chemoradiation.

Clinical features

Tumours from the anal area typically present as a mass associated with bleeding and pain (Figure 2). Even small lesions can produce significant local symptomatology, a "blessing in disguise" if it facilitates early detection [27]. Unfortunately, these symptoms are often erroneously attributed to "haemorrhoids", with subsequent delay in the diagnosis and treatment. It is important for the clinician to remember that haemorrhoids rarely cause pain (unless thrombosed), thus patients presenting with anal pain should be carefully evaluated, if possible under anaesthesia, and biopsies should be obtained. Untreated anal cancer spreads by local extension to adjacent tissues and organs of the pelvic floor, including sphincter muscles, vagina or prostate. When present, tenesmus, a painful urgency to defecate, suggests that the tumour has spread through the sphincter muscles [28]. A history of anorectal warts is present in 50% of homosexual men with anal cancer, but is found in only 20% of heterosexual individuals with SCCA [29].

Anal margin and anal canal tumours have different patterns of lymphatic drainage. Cancers arising from the more proximal anal canal (above the dentate line) drain predominantly into the peri-rectal and iliac lymph nodes, while tumours within the distal canal and the anal margin drain exclusively into inguinal lymph nodes. At presentation, approximately 50-60% of patients will have a superficial (T1 or T2) lesion, and 25% of patients will have involvement of regional lymph nodes.

10% of patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis [30].

Staging

Once the diagnosis of anal cancer has been established by biopsy, it is important to assess the regional extension of the tumour, and to further characterise its stage. Prognosis for anal cancer is related to tumour size, but it is unclear whether the independent variable is the actual tumour size or the depth of invasion. Neither the histology type, nor the degree of differentiation have major prognostic significance, and therefore have not been included in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/International Union Against Cancer (UICC) staging system (table 1) [31]. Tumours larger than 5 cm in greatest diameter (T3) and lesions with metastases in regional lymph nodes (N1-3) have an increased risk for tumour recurrence after chemoradiation (CRT) [32].

It should be noted that staging for most solid tumours is established according to the pathological examination of the surgical specimen. Staging systems for SCCA were validated at the time when abdomino-perineal resection (APR) was the first line therapy. Since most cases of anal cancer are now treated without surgery, a revised staging method for these cancers has yet to be developed.

Endoanal ultrasound currently represents the most promising modality to accurately determine the depth of penetration of anal cancer into the sphincter complex [33, 34]. A modification of the TNM classification for transanal ultrasound has been proposed by Bartram & Burnett in order to stage SCCA prior to chemoradiation (table 2) [35].

However, ultrasound-based staging systems are notoriously operator-dependent, and have so far failed to be validated in large series. Thus, surprisingly, there is currently no staging in routine use for SCCA either before chemoradiation or after APR [36].

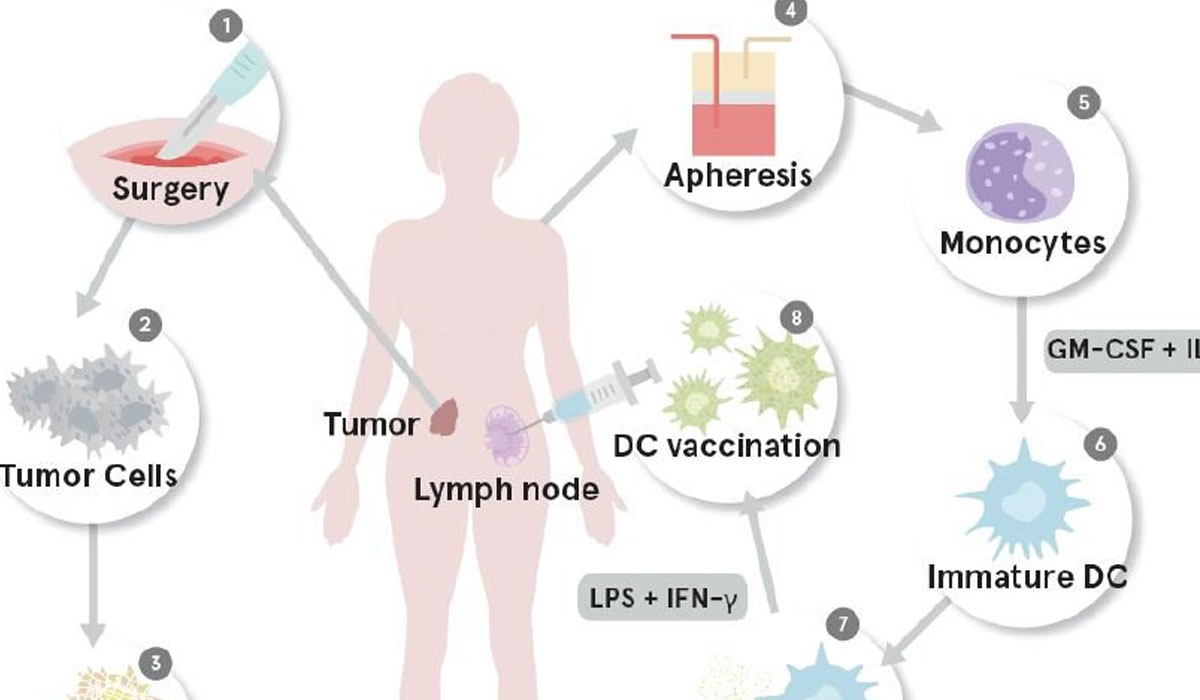

Treatment

In 1974, Nigro et al published their initial experience with preoperative radiation and chemotherapy followed by abdomino-perineal resection in three patients with SCCA. Unexpectedly, no residual tumour was found in the resected specimen. The same authors eventually confirmed these findings in a larger series [37]. Since then, it is commonly admitted that 1) SCCA is a radiosensitive carcinoma, 2) most anal cancers can be cured with chemoradiotherapy (CRT), and 3) APR is unnecessary in the majority of cases. However, despite good results with CRT as the primary means of management, approximately 30% of patients will develop a local recurrence [38]. Most patients with residual disease are ultimately candidates for an APR with definitive colostomy. Relatively good results can be achieved with salvage APR for recurrent SCCA with 5-year survival rates reported up to 50% in patients who had evidence of residual disease after CRT [39, 40]. The management algorithm for SCCA is summarized in figure 3.

Pascal Gervaz, MD

Clinique de Chirurgie Viscerale

Hopital Cantonal Universitaire de Geneve

Rue Micheli-du-Crest 24

CH-1211 Geneve

E-Mail: pascal.gervaz@hcuge.ch

References