Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Carcinoma of the Mediastinum

Carcinoma of the Mediastinum

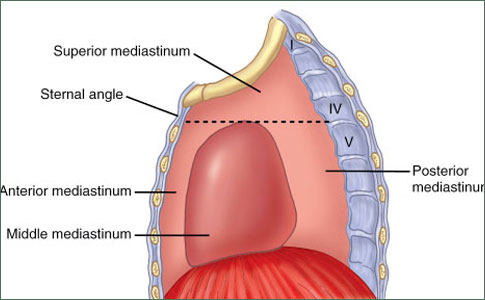

Mediastinal tumors are benign or cancerous growths that form in the area of the chest that separates the lungs. This area, called the mediastinum, is surrounded by the breastbone in front, the spine in back, and the lungs on each side. The mediastinum contains the heart, aorta, esophagus, thymus and trachea.

- The anterior (front)

- The middle

- The posterior (back)

Mediastinum tumors are mostly made of reproductive (germ) cells or develop in thymic, neurogenic (nerve), lymphatic or mesenchymal (soft) tissue.

Carcinoma of the Mediastinum

Introduction

Pathologic Evaluation

Diagnostic Evaluation

Treatment

References

Introduction

Occasionally, the biopsy diagnosis in a patient with a mediastinal tumor is "poorly differentiated carcinoma." This diagnosis poses difficult problems for the clinician, because it indicates a tumor with no histopathologic features specific enough to allow identification of the site of origin. Patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma in the mediastinum are sometimes assumed to have metastatic lung cancer with an undetectable primary lesion and are, therefore, assumed to be unresectable and incurable. In this setting, palliative radiation therapy is often administered. However, this approach is no longer adequate, because further clinical and pathologic evaluation can establish a definitive diagnosis with specific therapeutic implications in some of these patients. In addition, some patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma involving the mediastinum are curable with intensive cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Pathologic Evaluation

Critical pathologic evaluation of mediastinal tumors is essential, because a variety of neoplasms with specific therapeutic implications can arise in this location (eg, mediastinal germ cell tumor, lymphoma, thymoma). In addition, effective therapy also exists for some neoplasms that commonly metastasize to the mediastinum (eg, small-cell lung cancer). Following light microscopic examination of an adequate biopsy specimen, immunoperoxidase staining and electron microscopy are useful in distinguishing between the various neoplasms occurring in the mediastinum. By using these methods, lymphoma and neuroendocrine tumors (including small-cell lung cancer) can be reliably identified, and appropriate therapeutic approaches can be defined. Molecular genetic analysis should also be performed, if possible, because identification of an i(12p) chromosomal abnormality is diagnostic of a germ cell tumor.

Diagnostic Evaluation and staging Work-Up

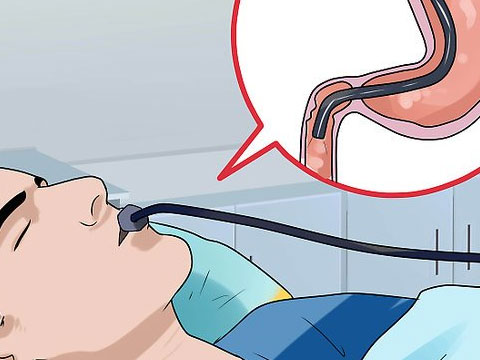

All patients should have CT scans of the chest and abdomen, as well as measurement of serum levels of HCG and α-fetoprotein. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy should be performed if other studies are nondiagnostic. Small-cell lung cancer should be suspected when neuroendocrine features are found in patients with a previous history of cigarette smoking.

Treatment

The diagnostic evaluation defines specific therapy for some patients in this group. Patients with elevated levels of either HCG or α-fetoprotein should be treated for a mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumor, even if this diagnosis is not made by histologic examination. Patients who have an endobronchial lesion found at bronchoscopy probably have lung cancer; those with neuroendocrine features should receive therapy for small-cell lung cancer, while those lacking these features should be treated for non-small-cell lung cancer.

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

Patients with poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma who lack risk factors and clinical features of small-cell lung cancer also have chemotherapy-sensitive tumors, and should be treated with platinum/ etoposide or paclitaxel/platinum/ etoposide regimens.

Primary Germ Cell Tumors of the Thorax

- Etiology

- Epidemiology

- Histopathology

- Clinical Characteristics

- Associated Syndromes

- Evaluation and Staging

- Treatment of Seminoma

- Treatment of Nonseminomatous Tumors

Introduction

Benign Teratomas of the Mediastinum

Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

Poorly Differentiated Carcinoma of the Mediastinum

References

There are several types of mediastinal tumors, with their causes linked to where they form in the mediastinum.

Anterior (front) mediastinum

- Germ cell - The majority of germ cell neoplasms (60 to 70%) are benign and are found in both males and females.

- Lymphoma - Malignant tumors that include both Hodgkin's disease and non Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Thymoma and thymic cyst - The most common cause of a thymic mass, the majority of thymomas are benign lesions that are contained within a fibrous capsule. However, about 30% of these may be more aggressive and become invasive through the fibrous capsule.

- Thyroid mass mediastinal - Usually a benign growth, such as a goiter, these can occasionally be cancerous.

Middle mediastinum

- Bronchogenic cyst - A benign growth with respiratory origins.

- Lymphadenopathy mediastinal - An enlargement of the lymph nodes.

- Pericardial cyst - A benign growth that results from an "out-pouching" of the pericardium (the heart's lining).

- Thyroid mass mediastinal - Usually a benign growth, such as a goiter. These types of tumors can occasionally be cancerous.

- Tracheal tumors - These include tracheal neoplasms and non-euplastic masses, such as tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (benign tumors).

- Vascular abnormalities including aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Posterior (back) mediastinum

- Extramedullary haematopoiesis - A rare cause of masses that form from bone marrow expansion and are associated with severe anemia.

- Lymphadenopathy mediastinal - An enlargement of the lymph nodes.

- Neuroenteric cyst mediastinal - A rare growth, which involves both neural and gastrointestinal elements.

- Neurogenic neoplasm mediastinal - The most common cause of posterior mediastinal tumors, these are classified as nerve sheath neoplasms, ganglion cell neoplasms, and paraganglionic cell neoplasms. Approximately 70% of neurogenic neoplasms are benign. Oesophageal abnormalities including achalasia oesophageal, oesophageal neoplasm and hiatal hernia. Paravertebral abnormalities including infectious, malignant and traumatic abnormalities of the thoracic spine. Thyroid mass mediastinal - Usually a benign growth, such as a goiter, which can occasionally be cancerous.

- Vascular abnormalities - Includes aortic aneurysms.

Symptoms and Signs

Many mediastinal masses are asymptomatic. In general, malignant lesions and masses in children are much more likely to cause symptoms. The most common symptoms are chest pain and weight loss. Lymphomas may manifest with fever and weight loss. In children, mediastinal masses are more likely to cause tracheobronchial compression and stridor or symptoms of recurrent bronchitis or pneumonia.

Symptoms and signs also depend on location. Large anterior mediastinal masses may cause dyspnea when patients are lying supine. Lesions in the middle mediastinum may compress blood vessels or airways, causing the superior vena cava syndrome or airway obstruction. Lesions in the posterior mediastinum may encroach on the esophagus, causing dysphagia or odynophagia.

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Fever

- Chills

- Night sweats

- Coughing up blood

- Hoarseness

- Unexplained weight loss

- Lymphadenopathy (swollen or tender lymph nodes)

- Wheezing

- Stridor (a high-pitched, noisy respiration, which can be a sign of respiratory obstruction, especially in the trachea or larynx)

Diagnosis

- Chest x-ray

- CT

- Sometimes tissue examination

Mediastinal masses are most often incidentally discovered on chest x-ray or other imaging tests during an examination for chest symptoms. Additional diagnostic testing, usually imaging and biopsy, is indicated to determine etiology.

CT with IV contrast is the most valuable imaging technique. With thoracic CT, normal variants and benign tumors, such as fat- and fluid-filled cysts, can be distinguished from other processes.

A definitive diagnosis can be obtained for many mediastinal masses with needle aspiration or needle biopsy. Fine-needle aspiration techniques usually suffice for carcinomatous lesions, but a cutting-needle biopsy should be done whenever lymphoma, thymoma, or a neural mass is suspected. If ectopic thyroid tissue is considered, thyroid-stimulating hormone is measured.

Treatment

Treatment depends on etiology. Some benign lesions, such as pericardial cysts, can be observed. Most malignant tumors should be removed surgically, but some, such as lymphomas, are best treated with chemotherapy. Granulomatous disease should be treated with the appropriate antimicrobial drug.

In a small percentage of patients, no evidence of tumor spread outside the mediastinum is detected. Surgical resection or local radiation therapy should be considered in these patients, usually in conjunction with empiric combination chemotherapy.

When mediastinal tumors are locally unresectable or have metastasized to distant sites, a trial of combination chemotherapy should be given to all patients with adequate performance status. We treated 43 patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma located predominantly in the mediastinum. These patients represented 19% of our entire group of patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma of unknown primary site. The median age was 38 years; 32 patients had other metastatic sites in addition to the mediastinum. Only 5 of 43 patients (12%) had elevated serum levels of HCG or α-fetoprotein. All patients received cisplatin-based chemotherapy; 13 patients (30%) had complete response, and 7 patients (16%) are long-term disease-free survivors. Review of the light microscopic features in these patients failed to reveal any previously unsuspected germ cell tumors or lymphomas.

In summary, patients with mediastinal tumors initially diagnosed as poorly differentiated carcinoma are a heterogeneous group. Some of these patients actually have well-defined tumor types that can be identified with additional pathologic or clinical evaluation. Patients in whom a specific tumor is identified should be treated according to standard guidelines for that tumor type. A trial of platinum/etoposide-based chemotherapy should be given to patients in whom no well-defined tumor type is recognized. Some of these patients have highly responsive neoplasms, and a minority appear to be cured with this treatment.

References