Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Esophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer

Demographics & Epidemiology

Esophageal cancer is a gastrointestinal malignancy with an insidious onset and a poor prognosis. The disease predominantly affects older age groups with a peak incidence between 60 and 70 years of age; it is rarely seen in children or young adults. There is also a predilection toward men with a ratio of at least 4:1. By far, the most common esophageal cancer worldwide is squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma accounts for less then 15% of all esophageal cancers. Other malignant tumors of the esophagus, such as sarcomas, lymphoma, primary malignant melanoma, and small cell carcinoma, are very rare (Table 18-1). Although considered relatively uncommon, esophageal cancer is the seventh most common cause of cancer-related deaths in men in the United States and has ranked among the top 10 causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

Esophageal cancer

Demographics & Epidemiology

Etiology

Natural History

¬ Clinical Presentation

¬ Complications

¬ Prognostic Factors

Diagnosis

Staging Techniques

Differential Diagnosis

Treatment

Surgery

¬ General Considerations

¬ Surgical Approach

Palliation Therapy

¬ Radiation Therapy

¬ Chemotherapy

¬ ¬ Single agent

¬ ¬ Combination chemotherapy

¬ ¬ Combined-modality therapy

¬ Endoscopic Therapy

¬ ¬ Dilation

¬ ¬ Ablation

¬ ¬ Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

¬ ¬ Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

¬ ¬ Esophageal prostheses

Prognosis

The incidence of esophageal cancer also differs significantly by geographic region and race. The rates can vary between regions in a given country, demonstrating an important role for environmental and possibly dietary/nutritional factors. Worldwide, the highest incidence of esophageal cancer is observed in Linxian, China, with an annual rate of more than 130 per 100,000 population. Other regions with high incidences of esophageal cancer include areas of Iran, Russia, Colombia, and South Africa. In the Western Hemisphere, the incidence is approximately 5-10 per 100,000 population. In the United States, the estimated number of new cases of esophageal cancer for the year 2000 was 12,300, with estimated deaths of 12,100.

Over the past two decades, the patterns of esophageal cancer have changed dramatically in the United States. Parallel changes are also seen in other Western countries. The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has risen sharply, especially among white males, whereas the rates of squamous cell carcinoma have remained essentially unchanged or have declined slowly. By the early 1990s, adenocarcinoma surpassed squamous cell carcinoma to become the most common type of esophageal cancer among white males, accounting for nearly 60% of all esophageal cancers, although squamous cell carcinoma remains the predominant cell type among African Americans. This change in the epidemiology of esophageal cancer is most likely multifactorial, involving a combination of factors and is not simply explained by the reclassification of gastric cardia carcinoma as esophageal adenocarcinoma or accounted for by the rising rate of Barrett's esophagus.

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

Etiology

Benign Esophageal Tumors

Benign esophageal tumors

General Considerations

Clinical Findings

¬ Symptoms and Signs

¬ Imaging

Treatment

References

Numerous studies have demonstrated that in developed countries cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption are the most important predisposing factors for esophageal cancer (Table 18-2). The carcinogenic effects of alcohol and tobacco are far more pronounced for squamous cell carcinoma than for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Although the mechanisms remain unclear, it is postulated that alcohol may act at several steps in the multiphase process of carcinogenesis, whereas the many tobacco-derived chemicals, such as nitrosamines, may affect the initiation of esophageal carcinoma or act as promotional agents.

It was previously thought that the total lifetime consumption of alcohol and amount smoked correlated with the risk of esophageal cancer. However, recent studies have shown the contrary; alcohol consumption and tobacco use do not affect the risk of esophageal cancer in the same way. For alcohol consumption, it is the mean intake (>200 g/week) rather than the duration, and for tobacco smoking, it is the duration (>15 years) rather than the mean intake that is more closely associated with the risk of esophageal cancer. In other words, a high intake of alcohol during a short period of time carries a higher risk than a moderate intake for a long time; a moderate consumption of tobacco for a long period carries a higher risk than a high intake for a short period. The risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma can be significantly reduced once patients achieve long-term smoking cessation (>10 years); however, the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma may remain elevated for up to 30 years from the time of smoking cessation

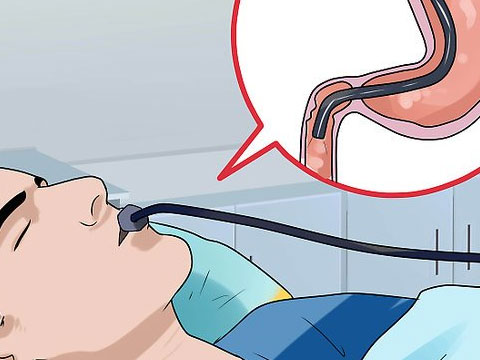

Whereas alcohol consumption and tobacco use are the most significant risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Barrett's esophagus is the most important risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett's esophagus, a known premalignant lesion, is a consequence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in which the squamous epithelium of the distal esophagus is replaced by intestinal-type columnar epithelium. Patients with GERD who develop Barrett's esophagus may have a certain degree of esophageal dysmotility. This usually results in a hypotensive or inappropriately relaxed lower esophageal sphincter (LES) allowing reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and ineffective peristalsis prolonging contact of refluxate with esophageal mucosa, thus causing esophageal epithelial damage. It is postulated that esophageal cancer evolves through a simliar temporal sequence of alterations seen in the dysplasia-to-carcinoma sequence in colonic neoplasm: metaplasia to low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia to adenocarcinoma. Barrett's esophagus is found in 10-15% of patients who undergo endoscopic evaluation for GERD. It is believed that this number probably underestimates the disease prevalence as many patients with Barrett's esophagus remain asymptomatic. The lifetime risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus is estimated to be 5%. In addition to its role in the pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus, GERD is an independent risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

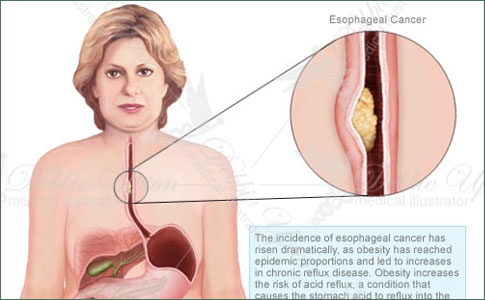

Recent epidemiologic studies have found that obesity (measured as body mass index) is another strong risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. The elevated risk is mainly associated with excessive weight per se and is not related to weight changes over time. Although the mechanism by which obesity contributes to the increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma is unclear, it has been speculated that obesity promotes gastroesophageal reflux disease by increasing intraabdominal pressure, which in turn predisposes to developing a chronic GERD state and Barrett's esophagus. Other factors that may affect the cancer risk associated with obesity include body fat distribution, dietary practices, medications, and other conditions that may affect the severity of GERD.

Several esophageal motility disorders have been implicated in the development of esophageal cancer. Long-standing achalasia has been associated with increased risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. On the other hand, scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) increases the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, perhaps through the development of Barrett's esophagus as the collagen deposits in the distal esophagus cause LES dysfunction. Other abnormalities or inflammatory lesions of the esophagus known to contribute to the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma include chronic esophagitis and strictures, tylosis, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, and lye ingestion.

In certain regions of the world, exceedingly high rates of esophageal cancer have been attributed to other environmental and dietary/nutritional factors. These include ingestion of hot foods and beverages, nitrate-containing preserved food, deficiencies in essential nutrients (carotene, riboflavin, vitamins C and E) and minerals (zinc and selenium), as well as infrequent consumption of fruits and vegetables. Human papillomavirus has also been implicated as a potential cause of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Interestingly, colon cancer and breast cancer are found to be associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer. More specifically, colon cancer is associated with adenocarcinoma, whereas breast cancer is associated with both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. The increased risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in breast cancer is greater in those who have received radiation therapy as part of their treatment. Radiation may damage the genetic repair mechanisms or cause chronic esophagitis and strictures, both of which predispose to the development of squamous cell carcinoma.

Natural History

Approximately 15% of esophageal cancers arise in the upper one-third of the esophagus, 50% in the middle third, and 35% in the lower third and at the gastroesophageal junction. The presenting symptoms tend to correlate with the location of the tumor. Unfortunately, many of the symptoms experienced by patients with esophageal cancer occur late in the course of the disease, at which time the disease is already at an advanced stage, resulting in a very poor prognosis.

The most common presentation of esophageal cancer leading to its diagnosis is progressive dysphagia (Table 18-3). The esophagus is capable of accommodating to the partial obstruction initially because it lacks a serosal layer so that the smooth muscle can stretch. As a result, a patient may not manifest dysphagia until the lumen is more than 50-60% obstructed by the tumor mass. The narrowed esophageal lumen leads to solid food dysphagia first and later to liquid dysphagia with further disease progression and obstruction. Regurgitation may also occur as the enlarging tumor narrows the esophageal lumen.

Odynophagia is the second most common presenting symptom of esophageal cancer. It may be due to an ulcerated area in the tumor or involvement of mediastinal structures, although mediastinal invasion would more typically present as constant pain in the midback or midchest. Anorexia and weight loss often ensue with decreased nutritional intake. Hoarseness or voice change appears when the tumor invades the recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing vocal cord paralysis. Severe cough and aspiration are usually the result of tumor invasion into the airway or development of a fistula between the esophagus and the tracheobronchial tree.

Overt gastrointestinal bleeding as manifested by hematemesis or melena is rarely encountered. However, anemia is relatively common at presentation. Chronic subclinical bleeding is a major contributing factor for anemia. Massive hemorrhage can rarely occur and may require emergent surgical treatment if endoscopic therapy fails.

B. Complications

Esophageal cancer readily extends through the thin esophageal wall due to the absence of a serosa to invade adjacent structures. The vital mediastinal structures adjacent to the esophagus include the trachea, the right and left bronchi, the aortic arch and descending aorta, the pericardium, the pleura, and the spine. Tumor infiltration into these structures accounts for the most serious and, sometimes, life-threatening complications of esophageal cancer.

Most complications due to esophageal cancer are attributed to luminal obstruction and local tumor invasion. Patients often subconsciously adjust their diets to soft or liquid foods to avoid solid food dysphagia. The progressive inability to swallow solids leads to weight loss and nutritional deficiencies. Solid food impaction can result when there is severe stenosis, requiring endoscopic intervention for disimpaction. Regurgitation of food or oral secretions may also occur in the setting of significant luminal obstruction. Halitosis may be present due to food stasis and regurgitation.

Pulmonary complications from aspiration include pneumonia and pulmonary abscess. The tumor mass may cause compression and obstruction of the tracheobronchial tree, leading to dyspnea, chronic cough, and at times postobstructive pneumonia. Esophagoairway fistula may develop with tumor invasion of the trachea or bronchus. Airway fistulas are severely debilitating and are associated with significant mortality owing to the high risk of pulmonary complications such as pneumonia and abscess.

Although the aortic arch and descending aorta lie adjacent to the esophagus, extension into these structures is less frequent than airway invasion. Erosion through the aortic wall can result in severe hemorrhage and is often fatal. Tumor ingrowth of the pericardium has been reported as an infrequent cause of arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities. Pleural effusions are usually small, but may signify pleural invasion when large effusions are present.

C. Prognostic Factors

1. Radiographic and endoscopic - Radiographic tests have been utilized to delineate the location and extent of esophageal involvement, as well as to stage the depth of tumor invasion, the presence of nodal involvement, and the presence of distant metastases. The length of esophageal involvement can be readily seen on barium esophagram and has been found to be a useful predictor of extraesophageal extension. Tumors measuring 5 cm are often confined to the esophageal wall whereas only 10% of those measuring >5 cm are localized. Computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest and abdomen are particularly useful in identifying distant metastases (most commonly to the liver and lung). The presence of metastases is a poor prognostic sign and is a contraindication to surgery.

For better evaluation of locoregional lymph node involvement and definition of depth of tumor penetration, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as the tool with the greatest accuracy (>80-90%). The primary advantage of EUS is as a staging modality. EUS is useful for identifying locally advanced disease after CT has ruled out metastatic disease. The presence of transmural invasion into adjacent organs such as the pericardium or trachea is associated with a poor prognosis. Evidence of lymph node involvement is also associated with a poor overall 5-year survival (20%).

2. Pathologic - Typically, the clinical prognosis of any malignant neoplasm depends on the histologic type and grade and the clinical stage. Esophageal cancer is no exception. The vast majority of esophageal tumors are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas. The former usually arise in the middle and the lower third of the esophagus whereas the latter are typically seen in the lower third. When compared stage to stage, there seems to be very little difference in the prognosis between the two. Rare esophageal malignancies associated with a poorer prognosis are small cell carcinoma and primary malignant melanoma. The overall prognosis of a poorly differentiated tumor is worse than that of a well-differentiated tumor.

3. Clinical stage - The revised tumor, nodes, metastasis (TNM) classification of 1997 is currently recommended for staging of esophageal cancer. The older classification system in which tumors were staged based on size, circumferential involvement, and extent of obstruction was abandoned. The new system recognizes five major prognostic stages (stage 0 to IV) of tumor extent and clearly defines the cancer stage based on local invasion of the tumor, nodal involvement, and presence of metastases (Table 18-4). According to the current classification, a T1 tumor is limited to the mucosa or submucosa. In stage T2, tumor invasion extends into but not through the muscularis propria. In stage T3, adventitia invasion is present. In stage T4, there is evidence of tumor invasion into adjacent structures such as the trachea, pericardium, or aorta. The 5-year survival rates associated with the depth of tumor invasion (T1 to T4) are approximately 80%, 45%, 25%, and 20%, respectively.

In the present TNM system, all local lymph node involvement is classified as N1, whereas nodal metastases outside the regional nodes (eg, cervical or celiac) and distant organ metastases are classified as M1. Distant nodal involvement is less serious than the blood-borne metastases to distant organs such as liver or lung, although the higher the number of nodes involved the worse the prognosis.

The disadvantage of the current TNM system is the lack of reference to the presence of lymphatic or blood vessel invasion adjacent to the tumor mass. These are important independent adverse prognostic factors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Blood vessel and lymphatic invasion should correlate with an advanced stage and presence of distant metastases.