Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Esophageal cancer Diagnosis

Esophageal cancer Diagnosis

Diagnosis

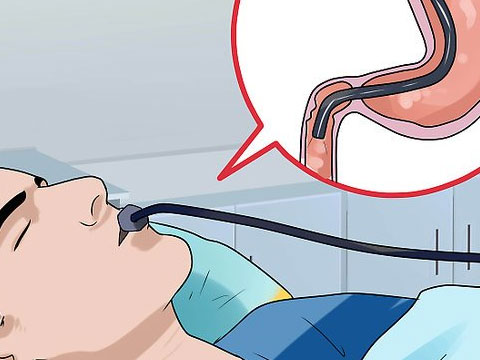

The initial diagnostic imaging test for most patients with dysphagia should be a barium esophagram (Figure 18-1). The study readily demonstrates narrowing of the esophageal lumen at the tumor site and dilatation proximally. Typical features of malignant obstruction on the barium esophagram include irregular mass lesions, irregular mucosal relief, and abrupt angulation of the esophageal contour (so-called tumor shelf). Benign lesions of the esophagus are typically associated with a smooth outline of the mucosa and symmetric narrowing without angulation or extrinsic compression.

Esophageal cancer

Demographics & Epidemiology

Etiology

Natural History

¬ Clinical Presentation

¬ Complications

¬ Prognostic Factors

Diagnosis

Staging Techniques

Differential Diagnosis

Treatment

Surgery

¬ General Considerations

¬ Surgical Approach

Palliation Therapy

¬ Radiation Therapy

¬ Chemotherapy

¬ ¬ Single agent

¬ ¬ Combination chemotherapy

¬ ¬ Combined-modality therapy

¬ Endoscopic Therapy

¬ ¬ Dilation

¬ ¬ Ablation

¬ ¬ Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

¬ ¬ Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

¬ ¬ Esophageal prostheses

Prognosis

Routine chest x-ray may reveal an esophageal air-fluid level above the site of obstruction or a pulmonary infiltrate from aspiration. A pleural effusion or mediastinal mass may suggest mediastinal tumor extension. Electrocardiogram changes are unusual except in cases of advanced pericardial invasion in which the normal conduction pathways may be impaired.

Figure 18-1. Barium esophagram showing mid-esophageal stricture. The abrupt change in caliber, irregular mucosa, and near circumferential narrowing are highly suggestive of an esophageal cancer.

Staging Techniques

Once the diagnosis is made, defining the stage of the esophageal cancer is the next essential step for further patient management. Previously, a significant number of patients with esophageal cancer went for exploratory surgery to attempt curative resection and/or for final staging. Unfortunately, this approach was disappointing as the majority of these patients were found to be inoperable due to extensive tumor invasion. At present, with advances in imaging techniques, the task of tumor staging is best accomplished by a combination of multiple imaging modalities, including EUS and CT or MRI. The current TNM classification for esophageal cancer was revised to reflect the improved preoperative staging available through these imaging studies.

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

Additional imaging for staging is necessary as contrast x-ray studies and endoscopy alone are often inaccurate for staging esophageal cancer because the extent of local invasion and presence of regional nodal and distant metastases cannot be determined. CT imaging has provided a nonoperative way to stage esophageal cancer. The standard CT imaging protocol for esophageal cancer involves the use of oral and intravenous contrast with examination from the upper chest to the upper abdomen, including the entire liver. The overall accuracy of CT for staging esophageal cancer is excellent for advanced disease. Liver metastases and findings consistent with adjacent organ invasion can be reliably noted on CT scan as well as by MRI. The sensitivity and specificity for detecting bronchotracheal and pericardial invasion exceed 90-95% in most series. However, CT imaging does not reliably detect local and regional lymph node metastases and "early" (T1-T2) tumors.

The advent of EUS offers the most significant advance in the preoperative staging of esophageal cancer. EUS is performed using a modified upper endoscope with an ultrasound transducer housed within the tip. At frequencies ranging from 7.5 to 12 MHz, EUS depicts five layers of the esophageal wall corresponding to its distinct histologic layers (Figure 18-2). Malignant tumors are identified as hypoechoic masses with irregular margins that disrupt the normal esophageal architecture. The depth of tumor invasion is defined by the outermost margin of the hypoechoic mass (Figure 18-3). Suspicious appearing lymph nodes are identified as hypoechoic rounded structures within the mediastinum and near the esophagus (Figure 18-4). Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of lymph nodes can be obtained through some EUS scopes for definitive diagnosis of malignant involvement (Figure 18-5). EUS can accurately diagnose early cancers, that is, those classified as T1-T2 (Figures 18-6 and 18-7). The overall accuracy of EUS for predicting the extent of esophageal cancers approaches 80-90% for T and 70-80% for N classification.

There are several limitations of EUS for staging esophageal cancer that need to be recognized. Overstaging of a T2 lesion can sometimes happen when there is significant peritumoral inflammation, whereas understaging sometimes occurs largely due to microscopic invasion beyond the muscularis propria. EUS is also very reliable in diagnosing adjacent organ invasion (ie, invasion to pleura or aorta) (Figures 18-8 and 18-9); however, limited depth of penetration of EUS results in incomplete assessment for distant metastases. In addition, about 30% of esophageal cancers produce severe esophageal obstruction and cannot be traversed with the regular ultrasound endoscope at the time of presentation. Generally, these tumors can be accurately staged with EUS after dilation of the stricture; and when this occurs, they are almost always advanced tumors, that is, T3 or greater (Figure 18-10). Recently, the development of through-the-scope miniprobes and wire-guided small-diameter blind ultrasound probes has overcome the problems with tumor strictures in most cases. In addition, as these small caliber ultrasound probes utilize higher scanning frequencies (12-20 MHz), the detection and accuracy of staging for T2 tumors has improved significantly.

Benign Esophageal Tumors

Benign esophageal tumors

General Considerations

Clinical Findings

¬ Symptoms and Signs

¬ Imaging

Treatment

References

A large number of studies have looked into the staging accuracy of EUS and CT scan. It has been demonstrated that EUS is more accurate than CT scan for locoregional staging (both T and N classification). EUS appears to be superior in defining abdominal lymph node metastases (especially celiac axis nodes), although CT scan is still the better imaging study to detect distant organ metastases. Nonetheless, CT scan should be considered as complementary to EUS and should be combined with EUS to determine the extent of extraesophageal invasion into the mediastinum and distant metastases. The ideal algorithm for managing these patients should include a CT scan of chest and abdomen, and, if negative for metastasis, an EUS should be done to rule out locally advanced disease.

A few other diagnostic tools have also been employed to assist in the staging of esophageal cancer. Bronchoscopy is widely used for assessment of bronchial invasion, primarily in mid-esophageal tumors. Although bronchial invasion is common, invasion into the bronchial lumen is rare. Therefore, bronchoscopy generally provides only indirect evidence of bronchial invasion, such as luminal indentation or narrowing. Diagnostic laparoscopy has been utilized in the assessment of peritoneal metastases. It offers the advantage of tissue biopsy under direct vision and an access for laparoscopic ultrasound. Thoracoscopy has also been used to better assess mediastinal and pulmonary metastases.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of patients with dysphagia or odynophagia includes esophageal mucosal diseases, motility disorders, and benign and malignant obstructing lesions. The insidious onset of progressive dysphagia to solids and then to liquids with associated weight loss in patients over 40-50 years of age almost invariably points to esophageal cancer. Patients with benign obstructing lesions of the esophagus, such as benign peptic strictures, webs and rings, and achalasia, may present with features resembling esophageal cancer. Barium esophagram offers indirect evidence for benign versus malignant processes; however, endoscopy with biopsies should still be employed to distinguish benign from malignant disease.

Achalasia is a motility disorder with impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and aperistalsis of the esophageal body. The classic radiographic appearance on the barium esophagram is a smooth, tapered distal esophagus referred to as a "bird's beak" appearance. Tumors at the gastroesophageal junction may at times mimic the signs, symptoms, and manometric findings of achalasia. Hence, endoscopy is required in all patients with suspected achalasia to exclude undiagnosed malignancy ("pseudoachalasia").

Malignant tumors of the esophagus other than squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are exceedingly rare. These tumors usually cannot be distinguished based on clinical grounds and require histologic confirmation. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma and cystic adenoid carcinoma of the esophagus are rare yet extremely aggressive and can be missed on endoscopic biopsy due to their primarily submucosal growth pattern.