Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Lung Cancer

Lung Cancer

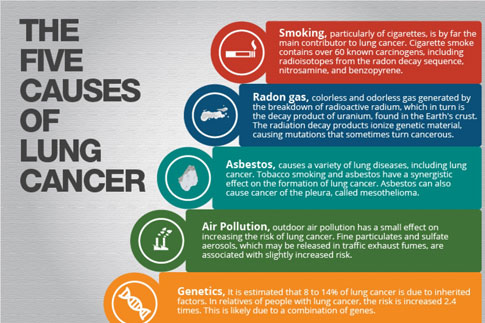

Lung Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors

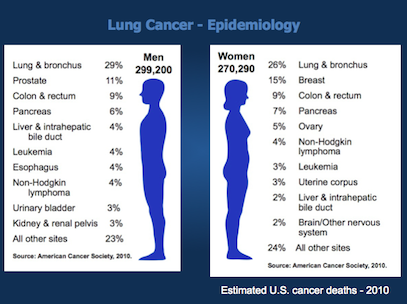

In the United States, the leading cause of cancer death in men is lung cancer, with lung cancer continuing to surpass breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer death in women. In men, the overall incidence of lung cancer currently approximates 80 per 100,000 men; this escalates to nearly 600 per 100,000 for men aged 60 to 79 years. In women, the overall incidence of lung cancer is approximately 50 per 100,000 women; lung cancer incidence rates are approximately 400 per 100,000 women aged 60 to 79. The number of older persons who will develop lung cancer is expected to increase as the smoking exposure time effects on birth cohorts become more apparent (Figure 35.1).

Lung Cancer

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis and Course of Illness

Treatment and Management of Illness

¬ Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

¬ Treatment of Small Cell Lung Cancer

Supportive Care

Conclusions

References

There is a dose-response relationship for smoking and lung cancer, and the risk for lung cancer increases with smoking duration, number of cigarettes smoked, age at onset of smoking, use of unfiltered cigarettes, tar and nicotine content, and degree of inhalation. The pivotal trial by Doll and Hill in 1956 showed that smoking cessation reduces the risk of lung cancer compared to those who continue to smoke. This finding was reproduced by Pathak et al. in 1986 in a case control study of lung cancer in New Mexico, which compared cases and controls less than 65 years of age to those more than 65 years of age and additionally showed that one decline in lung cancer risk that occurs with smoking cessation in the older person is comparable to that of the young. This same study showed that the number of years of smoking is relatively less important than the number of cigarettes smoked per day in determining the risk for lung cancer in those persons 65 and older.

In a reanalysis of the 1986 Adult Use of Tobacco Survey (AUTS), Orleans et al. found that older smokers smoked cigarettes with a slightly higher nicotine content than younger smokers.6 The number of cigarettes smoked per day was similar: 21.3 for smokers aged 21 to 49 and 29.1 for smokers aged 50 to 74. In this reanalysis, it was estimated that 53% of Americans aged 21 to 49 years were ever smokers, including 31% who were current smokers and 22% former smokers. In the 50- to 74- year-old group, 58% were ever smokers, including 23% current smokers and 35% former smokers. Although the older smokers had smoked for more than twice as many years as the younger group (mean, 39 years versus 16 years), the AUTS survey showed very little difference between the older and younger smokers in either smoking habits or quitting history. Even though the older smokers had smoked longer, they did not report an increased number of quitting attempts. The AUTS did suggest that older smokers underestimate both the risk of smoking and the benefits of stopping smoking (Table 35.1).

A recent American Cancer Society study clarified the risk of lung cancer mortality in smokers and former smokers. Halpern et al. examined and compared absolute and relative lung cancer death risk in former smokers as a function of age at cessation.7 In a prospective cohort study with 6 years of follow-up, the absolute risk of lung cancer mortality was compared in individuals who had never smoked and current and former smokers. As expected, there was a lower lung cancer death risk seen for those patients who quit smoking earlier in life, and the risk for those who were former smokers was significantly lower than for those who continued to smoke. However, the influence of age was profound (Figure 35.2A,B). The lung cancer death risk for persons who stopped smoking between the ages of 30 and 49 rose gradually with age at a rate slightly greater than for those persons who had never smoked. If one quit between the ages of 50 and 64, the lung cancer death risk leveled off at the risk attained at the time of quitting until around age 75, when it increased significantly.

For current smokers at age 75, the annual lung cancer mortality is estimated at 1 per 100 for males and 1 per 200 for females. Table 35.2 demonstrates the relative risk reductions as a function of age of smoking cessation. Former smokers had a relative risk of lung cancer death of approximately 0.45 if they had quit in their early sixties, 0.20 if they had stopped smoking in their early fifties, and 0.10 for those who had stopped smoking in their thirties, compared with nonsmokers who had a rela-tive risk of 0.05 or less. Therefore, in terms of reduced risk of lung cancer mortality, stopping smoking at any age is beneficial, but much more beneficial for those quitting at a younger age. The authors showed that even though the absolute lung cancer risk can plateau following smoking cessation, the lung cancer risk for former smokers is still consistently greater than that of those who have never smoked.

Family risk for lung cancer stronger…

Having a first-degree relative with early-onset lung cancer is a greater risk factor for developing lung cancer in blacks than in whites, according to a new…

In their model in Figure 35.2, the authors have shown that there is a rise in lung cancer risk seen after age 75, and this is consistent over several cohorts. This biologic difference in the older patient may reflect decline in cellular DNA repair activity with age, or perhaps the cumulative exposure to smoking and other carcinogens combined with decreased repair mechanisms late in life may have a synergistic effect on lung cancer risk. It is, however, also possible that this late rise is a reflection in the differing smoking characteristics of older and younger smokers, as mentioned earlier.

Although this study demonstrated that a greater reduction in lung cancer risk by smoking cessation at a young age, it also confirmed that stopping smoking is beneficial at any age, even in those patients beyond age 60. Because smokers benefit from quitting smoking and because one in four persons will be age 55 and older by the year 2010, it is important that health care providers counsel all patients on stopping smoking. Specifically, older patients are an important target for smoking cessation because they tend to be long-term, heavier smokers and are more likely to have chronic diseases that can be aggravated by smoking.

Pathogenesis

Because of the difference in natural history, survival, and type of treatment, primary bronchogenic carcinomas are commonly divided into two groups, non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. Histologically, non- small cell lung cancer can be subdivided into squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma, with bronchoalveolar cell being a subtype of adenocarcinoma. Non-small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 75% to 80% of all lung cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma was once the most common type of non- small cell lung cancer in this country; however, there has been an increase in adenocarcinoma, now accounting for approximately 40% of all lung cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma are highly associated with smoking, although cigarette smoking has been linked with all histologic subtypes. Although there are some differences in the clinical behavior of subtypes of non-small cell lung cancer, they are generally grouped together because of their similar natural history and response to treatment and because histology and cytology often overlap between these subtypes.

Small cell lung cancer can generally be distinguished from non-small cell lung cancer by histology or cytology alone in 95% of cases. Small cell lung cancer also tends to be detected at a more advanced stage because it grows rapidly and metastasizes early, with very few cases being surgically resectable. Non-small cell lung cancers, in contrast, tend to grow more slowly and are often detected at a stage where surgery may be curative.

The relative proportion of squamous cell cancer increases with increasing age and is particularly prevalent in older males. Squamous cell carcinoma was also found to be the subtype most likely to be detected at an early stage and with the best 5-year survival rate in the National Cancer Institute Early Lung Cancer Detection Program. Large cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are intermediate in their growth rate between squamous cell and small cell lung cancer. Adenocarcinoma is particularly prominent in females and is increasing in incidence. Importantly, adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma, like squamous cell carcinoma, may also present at a localized stage at which surgery is an option.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients with lung cancer are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Unfortunately, their symptoms are often associated with locally advanced or distant disease, which may render them inoperable (Table 35.3).

Specific signs and symptoms depend on the location of the tumor, its locoregional spread, and the presence of metastatic disease. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes occur more frequently in lung cancer than in any other tumor. Also, some patients are totally asymptomatic and for unrelated reasons undergo incidental chest x-ray and are found to have an asymptomatic lesion. Unfortunately, many of the symptoms of lung cancer are nonspecific and in the elderly may be attributed to comorbid illness. This may result in a delay in diagnosis, which may have profound effects on the treatment options available for the patient (Table 35.4).

A study by DeMaria and Cohen showed that patients at all ages had a similar prevalence of cough, hoarseness, dysphasia, and weight loss, but patients older than 70 years of age presented more frequently with dyspnea but less frequently with chest pain than did younger patients.

Although mass screening for lung cancer has not been recommended, high-risk patients over age 65 might benefit from screening to detect earlier-stage squamous cell carcinomas with favorable prognosis. It would seem logical that patients presenting with early-stage lung cancer are far more likely to be cured than those patients with advanced disease. However, over the past 30 years, the percentage of localized disease and resectability rates has remained unchanged at approximately 20%, indicating that screening and early detection programs have been unsuccessful.

Several prospective randomized studies using serial chest x-rays and sputum cytologies to complement each other in early lung cancer diagnosis did not result in detection of lung cancers at a curable stage or demonstrate that intensive screening led to a lower death rate from lung cancer. However, a study conducted by O'Rourke et al. suggested that lung cancer may present at a less advanced stage with increasing age. Information from the centralized cancer patient data system with a total of 22,874 cases showed that the percentage of lung cancer patients with local stage disease increased from 15.3% for patients aged 54 years or younger to 25.4% of those 75 years or older. An additional 6,332 patients who underwent surgical staging were analyzed and showed a greater likelihood of presenting with local disease with an increase in age. Therefore, in addition to having a higher age-specific incidence, older cancer patients may have a higher likelihood of local stage lung cancer. Thus, the older high-risk patient, smoker or former smoker, should be followed carefully for the development of lung cancer. In the absence of an official recommendation for routine screening, the physician should have a low threshold for obtaining a chest x-ray in these patients as symptoms develop.

The case for screening for lung cancer has recently resurfaced with the results of the Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP) group, who examined the usefulness of annual helical low-dose computed tomography (CT) scanning compared to chest x-ray in heavy smokers over the age of 60. Cancers were detected in 2.7% of patients by CT scan compared to 0.7% by chest x-ray; 85% of the CT-detected tumors were stage I and all but one were resectable. The overall rate of detection by CT scanning was six times higher than by chest x-ray. To prevent a large number of questionable biopsies, recommendations were made by the ELCAP investigators to initially biopsy only nodules with nonsmooth edges or noncalcified nodules 10 mm or larger. For smaller nodules, documented growth by high-resolution CT was recommended before biopsy. Biopsies were done on 28 of 233 patients with noncalcified lesions, with 27 having malignant disease and 1 having a benign nodule.

Despite these encouraging results, a number of problems still remain. First, the 27 cancers detected by CT scanning represented only one-quarter of all nodules found on CT scans, potentially necessitating a large number of follow-up scans. The need for biopsies, however, was maintained at a reasonable level, possibly because of recommendations offered by the investigators. Issues regarding cost also remain unclear although the investigators claim that the CT scan costs are only slightly higher than that of a chest x-ray and that only 20 s of CT time are required to obtain the images. Finally, the ability of annual screening CT scans to improve overall survival in smokers remains to be determined.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Once a patient is suspected of having lung cancer, a diagnosis should be confirmed by obtaining adequate specimens for pathologic analysis. Diagnosis is most commonly made from sputum cytology, bronchoscopy with bronchial washings, and biopsy or transthoracic needle aspiration. It has been shown that elderly patients tolerate such diagnostic procedures well, unless they have significant comorbid pulmonary conditions.

Figure 35.3 outlines a strategy based on location of the lung mass. Approximately two-thirds of neoplastic lesions can be seen through the fiber optic bronchoscope. In addition, those lesions that cause extrinsic narrowing of a bronchus can be biopsied transbronchially. The complications of bronchoscopy are minimal in experienced hands. The sensitivity for diagnosis when a lesion is visible is approximately 90%, and the specificity is excellent, with false positives occurring less than 1% of the time.

Bronchoscopy has essentially replaced the once common repeated samples of sputum for cytology because of the greater sensitivity of bronchoscopy. Washing and brushings are routinely obtained during bronchoscopy, and occasionally the cytology is diagnostic although the biopsy specimen is nondiagnostic. For more peripheral lung lesions or when the diagnosis cannot be made by bronchoscopy, transthoracic fine-needle aspiration (TTNA) and biopsy can be performed under fluoroscopic or CT guidance. This procedure, however, carries a much higher complication rate than bronchoscopy, with pneumothorax occurring in approximately 27% of patients and hemoptysis in 2% to 5%. It is, however, an alternative to more invasive procedures. TTNA may also be useful in aspiration of mediastinal structures, with no higher complication rate in the mediastinum than in a peripheral lung lesion. The incidence of false negatives with transthoracic needle aspiration and biopsy ranges from 11% to 69%. This rate can be improved by the presence of a pathologist at the time of the procedure to assure that an adequate sample has been obtained, and often a diagnosis can be made immediately in this setting.

The differential diagnosis for patients who present with abnormalities on chest x-ray includes lung cancer, as well as other nonmalignant conditions. These conditions include infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis or bacterial pneumonias, or inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis that can result in mediastinal lymphadenopathy and sometimes mimic locally advanced lung cancers. Patients with widely metastatic disease to the lungs are rarely mistaken to have other illnesses, and usually the major problem is confirming the primary source of malignancy.

Prognosis and Course of Illness

Once a tissue diagnosis has been made, staging becomes an important factor in the treatment of patients with lung cancer. Appropriate staging is critical to the prognosis and optional for treatment, as well as to compare results from different clinical treatment series and experimental clinical trials and to develop multimodality treatment regimens.

Mediastinoscopy, mediastinotomy, thoracotomy, and, more recently, video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) have been incorporated into the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Although video-assisted thoracoscopy remains an investigative tool, prospective studies are currently ongoing. It has proven to be useful in biopsing or excising peripheral nodules and sampling mediastinal nodes and is less invasive than standard thoracotomy (see Figure 35.3). All these techniques are useful adjuncts in staging lung cancer in appropriate patients. However, many patients present with signs of distant disease, such as distant lymph nodes, skin lesions, liver, adrenal, or bone involvement. Needle-directed biopsies in these patients can often confirm both the cell type and metastatic spread of the cancer and limit further need for evaluation.

Several studies have suggested that lung cancer presents at a less advanced stage in the elderly patient. Ershler et al., in a review of 157 lung cases in Vermont, showed that the percent of cases with metastatic disease decreased from 80% at age 40 to 40% at age 70. In a review of a centralized cancer patient data system, Crawford et al. analyzed 20,000 lung cancer cases registered between 1977 and 1982. There was an increase in the percent with local stage from 15.3% at age 54 and younger to 25.4% of those 75 or older. In those with distant disease, there was a decrease from 48.7% age 54 or younger to 36.7% age 75 or older.

In 1985, a new international staging system for lung cancer was adopted. The TNM classification groups patients according to the size and extent of their tumor (T), the lymph node involvement (N), and the presence or absence of metastatic disease (M). A patient's clinical stage is the best estimate of TNM before surgery, with the surgical stage of TNM determined after surgery and with pathologic review of surgical specimens (Table 35.5).

The TNM classifications can then be grouped into four stages of non-small cell lung cancer, with a significant difference in the 5-year survival depending on the stage at which the disease is diagnosed. Stages I and II represent surgically resectable disease, with stage III representing regionally advanced disease and stage IV distant metastatic disease (Table 35.6).

The TNM staging classification can be used in small cell lung cancer, but because of the more advanced stage at presentation, small cell carcinoma is generally classified as limited or extensive disease, similar to stage III or IV disease. In small cell lung cancer, limited disease is confined to one hemithorax and capable of being encompassed in a single radiation therapy port; this allows for mediastinal or supraclavicular nodal involvement and does not make a distinction between local and regional disease. Extensive disease is defined as metastatic spread beyond the limits of one hemithorax. Extensive disease occurs in two-thirds of small cell lung cancer cases. In small cell lung cancer, the distinction between limited and extensive disease is important in determining combined modality approaches with curative intent versus palliative chemotherapy. In addition, occasional patients present with a peripheral stage I small cell lung cancer and may undergo surgery.

It is important to stage all lung cancer patients before treatment and after therapy. A comprehensive history and physical examination are important to obtain symptoms suggesting regional spread, such as chest pain, hoarseness to suggest recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, or evidence of obstruction. In addition, symptoms such as bone pain, weight loss, or neurologic symptoms can suggest metastatic disease. Examination of the head and neck for lymphadenopathy may reveal lymphagitic spread.

The chest x-ray remains probably the most valuable tool in diagnosing lung cancer. However, CT plays an important role in staging of lung cancer, often detecting abnormalities that cannot be adequately evaluated on chest x-ray. The mediastinal structures, chest wall, and vertebrae can be evaluated with small pleural nodules or small pleural effusions often not seen on plain films shown on CT scans. In addition, the CT scan can detect metastatic disease to the liver or adrenals. It is important in staging a patient with lung cancer to include the upper abdomen to the level of the kidneys to evaluate for liver or adrenal gland abnormalities.

A CT scan can be helpful in selecting patients who should undergo mediastinoscopy. If the CT reveals mediastinal nodes greater than 1.5 cm in diameter, it should not be assumed that this indicates metastatic node involvement with tumor; histologic proof by thoracotomy or mediastinoscopy is indicated. This information is criti-cal for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) being considered for surgery. Developed some 30 years ago to facilitate staging of superior mediastinal lymph nodes, mediastinoscopy remains the most accurate lymph node staging technique to assess superior mediastinal lymph nodes that are frequently involved with disease. In a large study by Luke et al., the mortality rate of mediastinoscopy was zero with major morbidity rate less than 1%. In this study, it was reported that patients who were mediastinoscopy negative but found to have mediastinal lymph node involvement at thoracotomy had better 5-year survivals, compared with patients who were found at mediastinoscopy to have positive lymph nodes, who had much poorer survival.

In patients with small cell lung cancer, staging is important to determine if a patient has limited versus extensive stage disease. In addition to differences in prognosis, those patients with limited disease may also receive chest radiation and possibly prophylactic cranial irradiation. Thus, patients with small cell lung cancer should undergo brain CT or MRI to evaluate the presence or absence of CNS metastases. A CT scan including the upper abdomen to evaluate the liver and the adrenals as well as a bone scan are also important. Pretreatment staging will detect metastatic disease to the bone in approximately 38% of patients, metastases to the liver in 34% of patients, and CNS disease in 14% of patients. If these studies reveal no evidence of metastatic disease, bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be done because approximately 5% of patients have bone marrow involvement as the only site of metastatic disease.

Treatment and Management of Illness

Once the patient has a tissue diagnosis and has been accurately staged, the treatment plan can be determined. The patient's ability to tolerate treatment is of utmost importance, whether the planned therapy is surgery, ra-diation therapy, chemotherapy, or multimodality therapy. A patient's performance status has consistently been the single most prognostic factor for treatment planning. Patients who are asymptomatic with a Karnofsky performance status of 100% or symptomatic but normally active with a performance status of 80% to 90% generally tolerate therapy better and live longer than patients who have decreased performance status (Table 35.7). In addition, weight loss is also an important prognostic variable, with weight loss greater than 5% of body weight being an adverse predictor of survival.

Cancer is no less devastating to an elderly person than to a younger person. Older patients have the same right as younger patients to take part in the decision-making process about their treatment. Quality of life is equally important to older patients, and often they will prefer improved quality over quantity of life, with less interest in a trade-off of months or years of life in exchange for the side effects of treatment. Even though cancer is a disease of the elderly, older patients are often treated less aggressively; this can be explained somewhat by the presence of comorbid conditions that often exist in the elderly.

It may be that many physicians are uncertain about subjecting older patients to aggressive chemotherapy. Studies of the psychosocial impact of cancer treatments upon the elderly have shown that older patients are able to cope with the impact of chemotherapy as well if not better than younger patients. Older patients report no greater frequency of toxic side effects and often experience lower levels of emotional distress and life disruption than younger patients.

Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

The treatment of non-small cell lung cancer is highly dependent on accurate staging regimens, as already discussed. The following discussion delineates treatment plans based on accurate clinical staging.

Stages I and II

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for those patients with non-small cell lung cancer presenting with surgically resectable disease, that is, stages I, II, and possibly IIIa. Five-year survival for stage I is 60% to 80% and for stage II, 40%. In the elderly, extensive preoperative planning is necessary to determine the best surgical procedure for a complete resection of tumor with preservation of as much normal lung tissue as possible. If a pneumonectomy is being considered, the patient's pulmonary status must be adequately evaluated before surgery.

In the past, many physicians have viewed age greater than 70 as an independent risk factor for thoracotomy. However, because surgical resection remains the only potentially curative form for treatment for lung cancer and the life expectancy of patients age 70 is approximately 15 years, surgery should never be denied solely on the basis of a patient's age.

Massard et al. reviewed 1616 patients who underwent thoracotomy for lung cancer from January 1983 to December 1992, with 233 patients aged 70 years or more, at the University Hospital in Strasbourgh, France. Of these patients, 29% had no medical history, 26% had a history of cardiovascular disease, and 19% had a previous history of malignancy that was in complete remission; 48% of patients were stage I, 17% stage II, and 30% stage III. Of these, 210 patients were able to undergo resection, with 60 receiving pneumonectomies and 150 lobectomies. A total of 16 patients died postoperatively: 7.2% for the whole series, 10% after pneumonectomy, and 6.6% after lobectomy. The mortality was similar below and above 75 years of age. The 5-year survival for stage I was 45%, 36.3% for stage II, and 13.8% for stage III, with an overall 5-year survival of 39.9%. Survival was not influenced by age.

Patients who have complete resections are sometimes considered for adjuvant therapy with either chemotherapy or radiation therapy. These strategies attempt to reduce the risk of recurrence by treating presumed remaining tumor cells, either still in the chest (radiation) or disseminated to other sites (chemotherapy). Pre- and postoperative radiation therapy has not been shown to benefit survival in two large randomized trials. In addition, a recent meta-analysis also failed to demonstrate improvement in overall survival in completely resected patients who then went on to receive radiation therapy.

Despite advances in the treatment of breast and colon carcinomas with adjuvant chemotherapy, there continues to be no strong proof of survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in lung cancer, despite occasional trials that suggest a benefit. However, clinical trials involving newer agents are ongoing in the adjuvant setting and should be considered if available. In one study, patients with stage IB non-small cell lung cancers are being randomized to either observation alone or four cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Another large intergroup study is randomizing patients with completely resected stage II or stage III disease to either observation alone or four cycles of cisplatin and vinorelbine chemotherapy. Results from these studies are not expected to be available for a number of years, so until then, no firm recommendation of adjuvant chemotherapy can be given.

Operable Stage III

Surgery alone for stage III disease is associated with 5-year survival of less than 10%. In an attempt to improve long-term outcome of patients with this stage of disease, investigators have added chemotherapy preoperatively before a curative resection is attempted. In one study by Rosell et al., patients with IIIA disease (N2-ipsilateral node involvement) disease had improved survival after three courses of preoperative chemotherapy with mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin. Another study by Roth et al. demonstrated a 3-year survival of 56% for patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy compared with 15% for patients treated with surgery alone. Although these studies were not designed specifically for the geriatric population, nonetheless elderly patients were not excluded (in fact, the Rosell study had a patient aged 78 years in the combined treatment arm). The applicability of these studies to elderly patients remains questionable; however, elderly patients with good performance status and absence of other significant comorbidities should be considered for this treatment.

Inoperable Stage III

Radiation therapy has been the most common treatment in inoperable regional non-small cell lung cancer. It has also been considered an alternative treatment for those patients with underlying medical problems who cannot undergo surgery or those patients who decline surgical resection. The median survival for patients undergoing primary radiation therapy for unresectable disease is less than 1 year. Five-year survival data, however, show approximately 6% of patients alive and well with radiation therapy alone. This finding should not be compared with surgical results, because patients who are selected for radiation alone are usually patients with decreased performance status or other less favorable prognostic factors. Radiation therapy can be very useful in the palliation of symptoms resulting from thoracic tumor growth, such as intractable cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and chest pain. The major toxicity encountered is esophagitis, which is usually easily managed with patients who received radiation therapy without chemotherapy. Pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis are also important toxicities and, although rare, can result in significant morbidity in a patient population that already has preexisting pulmonary compromise.

Lung cancer may be one of the most common tumors treated with primary radiation therapy in the over-65 age group. There are several advantages to radiation therapy. There is no appreciable acute mortality associated with the treatment, and underlying comorbid conditions other than severe pulmonary disease do not often preclude radiation treatments. The normal healthy lung parenchyma can be preserved while relief of endobronchial obstruction is achieved, and the risk of a second malignancy is of less concern than in a younger patient. Relative disadvantages of radiation include the length of time involved in the course of treatment (often 4 to 6 weeks or more) and the side effects associated with radiation treatment, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, and lowered blood counts.

Because of the poor survival rates with radiation alone in stage III NSCLC and the frequent development of metastatic disease at distant sites, the role of chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy has been evaluated. In one study in which vinblastine and cisplatin chemotherapy plus radiation therapy was given, survival rates in years 1 to 7 were 54%, 26%, 24%, 19%, 17%, 13%, and 13%, respectively, in chemotherapy- and radiation-treated patients compared with 40%, 13%, 10%, 7%, 6%, and 6% for patients treated with radiation alone. The benefit of chemotherapy before radiation treatment has been confirmed by other studies as well. Another pivotal trial demonstrated that the concomitant treatment of inoperable NSCLC with cisplatin and radiation leads to improved local control of tumor as well as survival benefit. Thus, for good performance status patients with minimal weight loss, the combination of chemotherapy with radiation therapy should be strongly considered. What remains to be determined are the optimal chemotherapy agents used, as well as how they should be combined with radiation therapy.

Stage IV Metastatic Disease

Unlike small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy in advanced (stage IV) non-small cell lung cancer has shown marginal benefit. With the introduction of platinum-based chemotherapy, a modest survival benefit has been seen in patients. However, these benefits are usually brief and have been accompanied by a relatively high incidence of treatment-related toxicity. Best supportive care over chemotherapy remains a frequent choice, although there have been several studies that have shown a statistically significant survival advantage for combination chemotherapy over best supportive care. Much of the debate relates to the lack of quality of life studies in this setting to assess whether the modest improvement in survival is associated with improved quality of life as well.

Recent studies have actually suggested that elderly patients with NSCLC may have a better prognosis with treatment. Albain et al. analyzed 2531 patients with advanced-stage (IIIB/IV) NSCLC in the Southwest Oncology Group from 1974 to 1988 to assess the interactions of host- or tumor-related prognostic factors in therapy to determine whether each independently predicts outcome and define prognostic subsets with different survival potentials. It was found that a good performance status, female sex, and age greater than 70 years were significant independent predictors. Giovanazzi-Bannon et al., in an analysis from the Illinois Cancer Center, determined that there were no major differences between patients 65 years of age or more and patients less than 65 years of age when treated on phase II clinical trials. It was concluded that elderly patients should not be denied access to cancer clinical trials because of age alone. In this review, the older patients received slightly more courses of therapy with no significant difference between the two groups for treatment interruptions, days of delay, or number of dose reductions. When best response to therapy was analyzed, the elderly patients had more stable disease and less progressive disease than the younger patients. Older patients experienced only slightly more grade III or greater hematologic toxicities with no significant differences in other severe toxicities.

These results support the concept that at least some elderly patients can receive chemotherapy with similar benefit and side effects, if carefully selected based on good performance status and lack of comorbid disease, which are eligibility-applied to most clinical trials. However, application of these regimens to more dependent elderly populations requires further study, and very intensive regimens must be used with caution even in the well elderly. The importance of performance status as a predictor for the ability to tolerate polychemotherapy was most recently demonstrated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Patients with performance status two suffered more toxicity and had inferior survival compared with patients with better performance status.

More recently, the choice of chemotherapy agents useful for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer has increased; these include the cisplatin analogue carboplatin, the taxanes paclitaxel and docetaxel, the vinca alkaloid vinorelbine, the campthotecin irinotecan, and gemcitabine. In addition to being more effective compared with prior drugs, these compounds are also better tolerated and more easily delivered to patients. Furthermore, formal testing of these agents in elderly patients has now been undertaken.

The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group (ELVIS) investigators designed and executed a study to compare best supportive care in elderly patients with good performance status to single-agent chemotherapy with vinorelbine. Patients aged 70 years or older who had good performance status (defined as spending no more than 50% of the waking day in bed) were enrolled in the study. All patients had biopsy-proven non-small cell lung carcinoma, either stage IV or stage IIIB (malignant pleural effusions or metastatic disease to the supraclavicular lymph nodes). Treatment consisted of either best supportive care or vinorelbine 30 mg/m2 given on days 1 and 8. The chemotherapy was repeated every 3 weeks for a maximum of six cycles. Supportive care treatments were at the discretion of the physicians, and radiotherapy was allowed. No crossover was allowed. The major endpoints of the study included toxicity and response evaluations, a quality of life assessment, and overall survival. Baseline characteristics of the patients were well balanced in both arms. The median age was 74 years, with the majority of patients being men and having stage IV disease. Patients treated with vinorelbine demonstrated a clear survival benefit, with median survival increasing from 21 to 28 weeks; 1-year survival was extended from 14% in the best supportive care arm to 32% in the arm of patients receiving chemotherapy with vinorelbine. The overall response rate (complete and partial responses) was 19.7%. Results of the quality of life assessments were complicated by missing data (resulting from patient death and noncompliance) but nonetheless demonstrated a benefit of chemotherapy. Notable findings include benefits of vinorelbine in dyspnea, pain, and pain medicine consumption. Negative effects of chemotherapy included constipation, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, and peripheral neuropathy. However, only five patients discontinued therapy because of serious side effects, four due to severe constipation and one due to atrial arrhythmia.

This trial is of great importance as it is the first randomized trial of chemotherapy versus best supportive care in the elderly patient population. The results of this trial, as well as others, will make it difficult if not impossible for future trials to include a best supportive care arm. It is important to point out that the survival benefit of chemotherapy was not at the expense of high levels of toxicity and poor quality of life. The safety of this regimen is further suggested by a low level of hematologic toxicities and no treatment-related episodes of neutropenic fever or sepsis.

Vinorelbine has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and was the first of the "modern" chemotherapy drugs approved for lung cancer in the United States in more than 20 years. The combination of vinorelbine with cisplatin has been shown to be superior to single-agent vinorelbine, with single-agent vinorelbine chemotherapy producing a 1-year survival of 30% and a median survival of 31 weeks, whereas the combination led to a 35% 1-year survival rate with median survival time increasing to 40 weeks.

The effect and tolerability of monotherapy with gemcitabine has recently been examined in a series of patients over the age of 70 years who had good performance status. Patients received gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 given every week for 3 weeks, followed by a 1-week rest period; the cycle was then repeated every 4 weeks for a maximum of six cycles. Dose reductions and delays were made for hematologic toxicities. Forty-six patients were treated on the study, with the majority of patients being men with stage IV disease. The overall response rate including partial and complete responses was 22.2%. Ten patients who had symptoms demonstrated an improvement in their performance status on therapy. No WHO grade IV toxicities were demonstrated, there were no episodes of neutropenic fever, and no patients died due to complications of therapy. Two patients required discontinuation of therapy due to skin rash. Although this study does not demonstrate a meaningful benefit of single-agent gemcitabine on overall survival, it does suggest that the drug has activity, can improve the performance status of some patients receiving therapy, and has minimal toxicity. Furthermore, gemcitabine may be able to replace cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the elderly, given results of recent trials that demonstrate similar efficacy and better toxicity than the older standard regimen of cisplatin and etoposide.

Preliminary evidence also suggests that paclitaxel given weekly to elderly patients has efficacy and is well tolerated. One study treated patients over 70 years of age with paclitaxel and found a near 30% response rate coupled with symptom relief and minimal or absent side effects. Future studies will be needed to determine if a survival benefit exists similar to that seen in the ELVIS trial.

It is hoped that these new agents will lead to more substantial gains in both quality of life and survival for patients with advanced NSCLC.

Treatment of Small Cell Lung Cancer

Surgery is rarely thought to be an option in small cell lung cancer. However, approximately 3% of small cell lung cancer patients present with a solitary peripheral nodule. Surgical resection of the tumor in these patients has been associated with a 5-year survival rate greater than 30%. In those patients presenting with a stage I small cell lung cancer, surgery should be considered as primary treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without radia-tion therapy postresection. Chemotherapy is the most important component of small cell lung cancer treatment because of the sensitivity of small cell lung cancer to chemotherapy and the systemic nature of the disease. Patients with limited-stage disease treated with combination chemotherapy have a median survival of approxi-mately 14 to 15 months and 9 months for extensive-stage disease. There is a 2-year disease-free survival of approxi-mately 13% in patients with limited-stage disease, with only 2% long-term survival in patients with extensive-stage disease. The development of tumor resistance to chemotherapy appears to be a major factor contributing to relapse. Small cell lung cancer cells are quite sensitive to radiation therapy, and therefore radiotherapy is best used early in treatment in combination with chemotherapy in patients with limited-stage disease and good performance status, with the potential to increase the curability of this disease. In the elderly, however, the benefits of combined modality therapy must be balanced against the increased toxicities, particularly myelosuppression, pulmonary toxicity, fatigue, and anorexia. Thus, supportive care is critical in the success of combined modality approaches in this population.

The management of limited-stage small cell lung cancer continues to consist of a treatment plan combining chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A meta-analysis of trials comparing chemotherapy with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy demonstrated a small, albeit significant, improvement in overall survival in patients who received a combined approach. However, questions still remain on the best way to combine chemotherapy with radiotherapy, especially given the increased toxicity with the combination. One recent study has suggested that twice-daily radiotherapy improved survival in patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer. Patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer were treated with four cycles of cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy given every 21 days. Patients were randomized to receive a standard dose of 45 Gy of concurrent radiation given either twice daily over a 3-week period or once daily over a 5-week period. The median age of the patient population was 62 years, with patients aged over 65 years comprising 31% and 40% of the two arms. At 5 years, 26% of patients receiving twice-daily radiotherapy were alive compared with 16% of patients receiving once-daily radiotherapy. The improvement in survival was at the expense of increased esophageal toxicity in the twice-daily treated group, but no differences in hospitalization or esophageal perforation, and no strictures, were noted. Whether the results of this trial can be generalized to the geriatric population remains to be determined.

One controversial area in the management of small cell lung carcinoma concerns the use of prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) for patients with complete responses to chemotherapy. Advances in radiotherapy techniques have reduced the rate of recurrent disease in the chest; however, these patients continue to be at high risk for the development of systemic metastasis, mainly to liver, bone, adrenal glands, and brain. At diagnosis, only 10% to 20% of patients have brain metastasis, while at 2 years post- diagnosis nearly 50% of patients developed brain metastasis. Because of the blood-brain barrier inhibiting chemotherapy effects, the brain has been believed to be a sanctuary site for subclinical metastasis. Investigators over the years have thought that giving radiotherapy to the whole brain may prevent the development of brain metastasis and positively impact on quality of life and overall survival. Randomized trials have demonstrated a clear reduction in the development of brain metastasis; however, an impact on survival was unclear given the low numbers of patients randomized. Coupled with this enthusiasm, however, came the worry about a deleterious effect on neuropsychologic functioning. Subsequently, studies have demonstrated that a high proportion of patients with limited-stage SCLC had preexisting cognitive dysfunction before receiving PCI, which might have influenced previous studies. To get a better idea of whether PCI can impact patient survival, a meta-analysis was performed on individual data from studies that randomized patients demonstrating a complete response to chemoradiotherapy, to PCI, or to no PCI. PCI decreased the cumulative incidence of brain metastasis by nearly 50%, which translated to a 5% increase in the rate of survival at 3 years. The median age of patients in this trial was 59 years, with a range up to 80 years. Again, whether this trial can be generalized to elderly patients remains in question. Subgroup analysis, despite its known limitations, did not demonstrate any difference in benefit as a function of age.

Controversy continues over the benefit of treating elderly patients with chemotherapy, given commonly held views that they are less tolerant compared with younger patients. Elderly patients may be at increased risk of myelosuppression because of less marrow cellularity, as well as impaired renal and hepatic function that alters drug metabolism and excretion. Comorbid disease, often the result of years of smoking, also limits the enthusiasm of oncologists to treat elderly patients. Indeed, in elderly small cell lung carcinoma patients, nearly three-quarters had comorbid disease, including coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and second malignancies. Biases against the treatment of small cell lung cancer in the elderly may not be justified. For example, Shepherd et al. found that elderly patients can tolerate chemotherapy and derive a survival benefit. The delivery of chemotherapy was impaired, however, with most patients requiring dose reductions, and less than half of the patients completed six cycles of chemotherapy. These and other studies that have demonstrated similar response rates and overall survival in young and old SCLC patients have made the oncology community reevaluate its view of treating elderly patients with SCLC. Even single-agent chemotherapy, such as with etoposide, can result in high response rates and improvements in survival. Finally, the addition of colony-stimulating factors such as G-CSF and erythropoietin may allow for more aggressive treatment of these patients. We believe that all elderly patients with small cell lung cancer should receive oncology consultation and those that are medically fit and interested in the palliation and survival benefits offered by chemotherapy should receive treatment.

Supportive Care

Just as elderly patients are often not treated aggressively for lung cancer, the associated side effects of their diseases or treatment may not sufficiently be addressed. Elderly patients with cancer require substantial supportive care. The goal of all supportive therapy should be to maximize the ability of the patient to tolerate both the disease and its treatment.

Patients may present to their physician complaining of unexplained weight loss and loss of appetite and may subsequently be diagnosed with cancer. Cancer cachexia is common in patients with advanced metastatic disease but may also occur in patients with localized disease. Anorexia with abnormalities in taste perception, such as intolerance for sweets, sour, or salty flavors, as well as an aversion for meats, may exist before initiation of treatment and subsequently be exacerbated by the initiation of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Substantial weight loss, which is progressive, and a malnourished state often prevent a patient from being treated. Treatment should include counseling of the patient and family members as to why the symptoms are present, consultation with a dietician to discuss meal planning and preparation, and often treatment with medications such as megestrol acetate or prednisone that may stimulate the appetite.

Improvements in antiemetics with the use of serotonin antagnoists, as well as the use of colony-stimulating factors to ameliorate neutropenia and its complications when appropriate, have had a major impact on the supportive care of the cancer patient receiving chemotherapy. These agents may particularly be useful in the elderly and assist the physician in the decision to use chemotherapy in the elderly lung cancer patient. Recently, the benefit of recombinant erythropoietin on quality of life was described in patients receiving chemotherapy for nonmyeloid malignancies. In this study, patients were treated with erythropoetin-alpha 10,000 units three times weekly, which could be increased to 20,000 units three times weekly depending on the hematologic response. This therapy was associated with improvements in quality of life scores that were well correlated with levels of hemoglobin. A large number of patients had cancer of the lung and were being treated with modern chemotherapy regimens, including carboplatin/paclitaxel, carboplatin/etoposide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin/etoposide. The mean increase in hemoglobin was approximately 2 g/dL with nearly two-thirds of patients responding to erythropoetin-alpha. Tumor type, tumor response to chemotherapy, performance status, chemotherapy regimen, baseline hemoglobin, and baseline erythropoietin levels were not found to correlate with quality of life responses. Although not specifically targeting the elderly population, nonetheless the median age of lung cancer patients was 65 years.

Of increasing importance in patients with lung cancer is the coexistence of depression, which can serve as a predictor of quality of life. Recently, the rates of depression were reported in patients with both small and non-small cell lung cancer. Depression existed in one-third of patients before the initiation of treatment and persisted in more than 50% of patients. Multivariate analysis revealed that functional impairment was the most important risk factor for the development of depression, along with physical symptom burden and fatigue. Age was not a risk factor for the development of depression; rather, there was a nonsignificant trend toward lower rates of depression in older patients.

Conclusions

The epidemic of lung cancer continues in the United States, and the elderly remain the major target. Despite a decline in smoking by men in the United States, antismoking campaigns have not been successful in preventing teenage smoking or in decreasing the percent of women who smoke, so the epidemic will continue.

Despite the high mortality of lung cancer, however, long-term survival is now possible, not only for surgically resected patients but also for some patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer or limited-stage small cell lung cancer. Even in advanced disease, significant improvement have been made by the use of chemotherapy and supportive care in appropriate patients. Elderly patients with lung cancer deserve careful evaluation of treatment options in a multidisciplinary setting.

References

1. Ginsberg RJ, Vokes EE, Rosenzweig K. Cancer of the lung. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology, 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:925-983.

2. Yancik R, Reis LA. Cancer in older persons - magnitude of the problem. How do we apply what we know? Cancer. 1994;74(suppl1):1995-2003.

3. Doll R, Hill AB. Lung cancer and other causes of death related to smoking: a second report on the mortality of British doctors. Br Med J. 1956;2:1071-1081.

4. Pathak DR, Samet JM, Humble CG, et al. Determinants of lung cancer risk in cigarette smokers in New Mexico. JNCI. 1994;76:597-604.

5. Crawford J, O'Rourke MA, Cohen HJ. Age factors in the management of lung cancer. In: Yancik R, Yates JW, eds. Cancer in the Elderly. New York: Springer; 1989:177-203.

6. Orleans TC, Jepson C, Resch N, et al. Quitting motives and barriers among older smokers; the 1987 Adult Use of Tobacco Survey revisited. Cancer (Suppl). 1994;74:2055- 2061.

7. Halpern M, Gillespie B, Warner K. Patters of absolute risk of lung cancer: mortality in former smokers. JNCI. 1993;85:457-464.

8. Rimer BK, Orleans TC. Tailoring smoking cessation for older adults. Cancer (Suppl). 1994;74:2051-2054.

9. DeMaria LC, Cohen HJ. Characteristics of lung cancer in the elderly patients. J Gerontol. 1987;42:540-545.

10. O'Rourke MA, Feussner JR, Ferge P, et al. Age trends of lung cancer at diagnosis. JAMA. 1987;258:921-926.

11. Rimer BK, Heman D, Crawford J, et al. Lung cancer in North Carolina. NC Med J. 1993;54:334-341.

12. Henschke C, McCauley D, Yankelevitz D, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354:99-105.

13. Vaporciyan AA, Nesbitt JC, Lee JS, et al. Cancer of the Lung. In: Bast RC, Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, Holland JF, Frie E, eds. Cancer Medicine, 5th ed. Ontario: BC Decker, Inc. 2000:1227-1292.

14. Ershler EB, Socinski MA, Greene CJ. Bronchogenic cancer, metastases and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;31:673-676.

15. Luke WP, Pearson FG, Todd TFJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of medianstinoscopy for assessment of carcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;91:53-56.

16. McKenna RJ. Clinical aspects cancer in the elderly. Treatment decisions, treatment choices, and follow up. Cancer. 1994;74:2107-2117.

17. Walsh SJ, Begg CB, Carbone PP. Cancer chemotherapy in the elderly. Semin Oncol. 1989;16:66-75.

18. Massard G, Moog R, Wihlm JM, et al. Bronchogenic cancer in the elderly: operative risk and long-term prognosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;44:40-45.

19. PORT Meta-analysis Trialists Group. Postoperative radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: systemic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from nine randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 1998;352:257-263.

20. Rosell R, Gomez-Codina J, Cmaps C, et al. A randomized trial comparing preoperative chemotherapy plus surgery with surgery alone in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:153-158.

21. Roth J, Rossella F, Komaki R, et al. A randomized trial comparing perioperative chemotherapy and surgery with surgery alone in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. JNCI. 1994;86:673-680.

22. Crocker I, Prosnitz L. Radiation therapy of the elderly. In: Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, vol III. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1987:473-478.

23. Dillman RO, Seagren SL, Propert KJ, et al. A randomized trial of induction chemotherapy plus high dose radiation versus radiation alone in stage III non small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:989-990.

24. Dillman R, Herndon J, Seagren S, Eaton W, Green M. Improved survival in Stage III non-small cell lung cancer: seven-year follow-up of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 8433 Trial. JNCI. 1996;88:1210-1215.

25. Schaake-Koning C, van den Bogert W, Dalesio O, et al. Effects of concomitant cisplatin and radiotherapy on inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:524-530.

26. Souquet PJ, Chauvin F, Boissel R, et al. Polychemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a metaanalysis. Lancet. 1993;342:19-21.

27. Grilli R, Oxman A, Julian JJ. Chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: how much benefit is enough? J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1966-1972.

28. Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, et al. Survival determinants in extensive stage non-small cell lung cancer: The Southwest Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1618-1626.

29. Giovanazzi-Bannon S, Rademake A, Lai G, et al. Treatment tolerance of elderly cancer patients entered onto Phase II clinical trials: an Illinois cancer center study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2447-2452.

30. Johnson DH, Zhu J, Schiller J, et al. E1494: a randomized phase III trial in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) - outcome of performance status 2 patients: an Eastern Cooperative Group Trial (ECOG). Proceedings American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;18:461a [abstract 1779].

31. The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group. Effects of vinorelbine on quality of life and survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JNCI. 1999;91:66-72.

32. LeChevalier T, Brisgand D, Douillard J-Y, et al. Randomized study of vinorelbine and cisplatin alone in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results of a European multicenter trial including 612 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:360- 367.

33. Shepherd FA, Abratt RP, Anderson H, et al. Gemcitabine in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(2):S7-S50.

34. Fidias P, Supko J, Martins R, et al. A phase II clinical and pharmacokinetic study of weekly paclitaxel in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2000;29(1):57 [abstract 184].

35. Turrisi A, Kim K, Blum R, et al. Twice-daily compared with once-daily thoracic radiotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer treated concurrently with cisplatin and etoposide. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:265-271.

36. Komaki R, Meyers C, Shin D, et al. Evaluation of cognitive function in patients with limited small cell lung cancer prior to and shortly following prophylactic cranial irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:179-182.

37. Lishner M, Feld R, Payne D, et al. Late neurological complications after prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with small-cell lung cancer: the Toronto Experience. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:215-221.

38. Auperin A, Arriagada R, Pignon J, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. N Engl J Med. 1999;314:476-484.

39. Shepherd FA, Amdemicheal E, Evans WK. Treatment of small cell lung cancer in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:64-70.

40. Foley KM. Supportive care and the quality of life in the cancer patient. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology, 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1993:2417-2448.

41. Daly JM, Torosian MH. Nutritional support. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology, 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott;1993: 2480-2501.

42. Demetri G, Kris M, Wade J, Degos L, Cella D, for the Procrit Study Group. Quality-of-life benefit in chemotherapy patients treated with Epoetin Alfa is independent of disease response or tumor type: results from a prospective community oncology study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3412-3425.

43. Hopwood P, Stephens RJ, Fletche I, Lee A. The impact of depression on quality of life and survival in patients with inoperable lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2000;29(1):272 [abstract 931].