Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Malignant mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors

Malignant mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors

Etiology

Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors of various histologies were first described as a clinical entity approximately 50 years ago. Mediastinal and other extragonadal germ cell tumors were initially thought to represent isolated metastases from an inapparent gonadal primary site. However, there is now abundant clinical evidence to substantiate the extragonadal origin of these tumors. Extragonadal germ cell tumors, particularly those arising in mediastinal and pineal sites, represent a malignant transformation of germinal elements distributed to these sites and can occur in the absence of a primary focus in the gonad. Some investigators suggest that this distribution arises as a consequence of abnormal migration of germ cells during embryogenesis. Others hypothesize a widespread distribution of germ cells to multiple sites during normal embryogenesis, with these cells conveying genetic information or providing regulatory functions at somatic sites.

Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors

Etiology

Epidemiology

Histopathology

Clinical Characteristics

Associated Syndromes

Evaluation and Staging

Treatment of Seminoma

Treatment of Nonseminomatous Tumors

Epidemiology

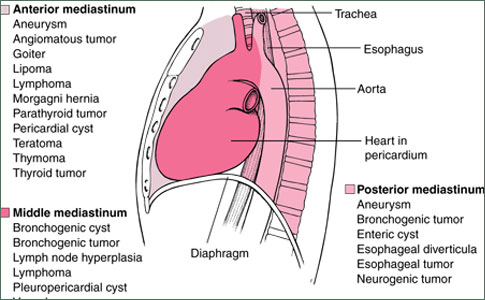

Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum are uncommon, representing only 3 to 10% of tumors originating in the mediastinum. They are much less common than germinal tumors arising in the testes, and account for only 1 to 5% of all germ cell neoplasms. These figures, most of which are derived from retrospective series reported between 1950 and 1975, may underestimate the true occurance of mediastinal germ cell tumors. The histology of these tumors may be similar to that of other malignant mediastinal tumors, including malignant thymoma and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Some patients with "poorly differentiated neoplasm" or "poorly differentiated carcinoma" of the mediastinum have the i(12p) chromosomal abnormality diagnostic of germ cell tumor. Other patients with "poorly differentiated carcinoma" of the mediastinum have clinical characteristics and treatment responses typical of patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Although there is no doubt that mediastinal germ cell tumors are uncommon, increasing familiarity with the tumors by both clinicians and pathologists will probably result in their increased recognition.

The great majority of mediastinal malignant germ cell tumors occur in patients between 20 and 35 years of age. For unknown reasons, most are found in males. In the rare occurrences reported in females, mediastinal malignant germ cell tumors have appeared histologically and biologically identical to those occurring in males. The relative rarity of extragonadal germ cell tumors in women parallels the lower incidence of female gonadal germ cell tumors as compared with their incidence in males. Although the incidence of primary testis tumors is low amongst racial minorities in the United States, the occurrence of extragonadal germ cell tumors is somewhat more common (7% versus 16% of cases, respectively).

Histopathology

In general, mediastinal germ cell tumors appear histologically identical to germ cell tumors arising in the testis, and all histologic subtypes seen in gonadal germ cell neoplasms have also been recognized in the mediastinum. In a recent review of 229 malignant mediastinal germ cell tumors seen between 1960 and 1994 at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, pure seminoma was the most common histology, accounting for 52% of cases. Nonseminomatous histologies included teratocarcinoma (20%), yolk-sac tumor (17%), choriocarcinoma (3.4%), embryonal carcinoma (2.6%), and mixed nonseminomatous tumors (5.2%).

Anal Cancer: Strategies in Management

The management of anal cancer underwent an interesting transformation over the last two decades.

Clinical Characteristics

Unlike benign germ cell tumors of the mediastinum, malignant mediastinal tumors are usually symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Most mediastinal malignant tumors are large and cause symptoms by compressing or invading adjacent structures, including the lungs, pleura, pericardium, and chest wall. Pure seminomas are somewhat slower growing and have less potential for early metastasis than do tumors with nonseminomatous elements; their initial presentation, therefore, varies somewhat. Pure seminomas and tumors with nonseminomatous elements are discussed separately, although a great deal of overlap exists in their clinical characteristics.

Seminoma Seminomas grow relatively slowly and can become very large before causing symptoms. Tumors 20 to 30 cm in diameter can exist with minimal symptomatology. Approximately 20 to 30% of seminomas are detected by routine chest radiography while still asymptomatic. The most common initial symptom is a sensation of pressure or dull retrosternal chest pain. Additional symptoms include exertional dyspnea, cough, dysphagia, and hoarseness. Superior vena caval syndrome develops in approximately 10% of patients. Systemic symptoms related to metastatic lesions are uncommon.

Carcinoma of the Mediastinum

Introduction

Pathologic Evaluation

Diagnostic Evaluation

Treatment

References

At the time of diagnosis, only 30 to 40% of patients with mediastinal seminoma have localized disease; the remainder have one or more sites of distant metastases. The lungs and other intrathoracic structures are the most common metastatic sites. The skeletal system is the most frequently involved extrathoracic metastatic site; the propensity of advanced testicular seminoma to metastasize to bone has also been recognized. The retroperitoneum is an uncommon site of metastasis in patients with mediastinal seminoma.

Pure seminoma appears radiographically as a large, noncalcified anterior mediastinal mass, which can compress or deviate the trachea or bronchi if of sufficient size. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest typically shows a large homogeneous anterior mediastinal mass that obliterates the fat planes surrounding mediastinal vascular structures. The radiographic findings are not specific enough to allow the distinction of mediastinal seminoma from other mediastinal tumors.

Elevated serum levels of HCG are detected in approximately 10% of mediastinal seminomas. This incidence is similar to that reported in advanced testicular seminoma. Levels of HCG exceeding 100 ng/mL are unusual, and suggest the presence of nonseminomatous elements. The serum α-fetoprotein level is always normal in pure mediastinal seminoma, and any elevation of this tumor marker indicates the presence of nonseminomatous elements. Serum lactic dehydrogenase is also elevated in the majority of patients with mediastinal seminoma.

Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumor Very few patients with these rapidly growing neoplasms are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Symptoms caused by compression or invasion of local mediastinal structures are identical to those seen in patients with mediastinal seminoma. However, presenting symptoms caused by metastatic lesions are much more common, because 85 to 95% of these patients have at least one metastatic site at the time of diagnosis. Common metastatic sites include the lungs, pleura, lymph nodes (particularly supraclavicular and retroperitoneal), and liver. Less frequent sites of involvement include the bone, brain, and kidney. High levels of HCG sometimes are associated with gynecomastia. Neoplasms with elements of choriocarcinoma have a marked hemorrhagic tendency; these patients may have catastrophic events related to uncontrolled hemorrhage at a metastatic site (eg, massive hemoptysis, intracranial hemorrhage). Constitutional symptoms, including weight loss, weakness, and fever, are more common in these patients than in those with pure seminoma.

Chest radiographic features of mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are similar to those seen in mediastinal seminomas. The CT scan frequently shows an inhomogeneous mass, with multiple areas of hemorrhage and necrosis, differing from the usually homogeneous appearance of mediastinal seminoma.

The serum tumor markers HCG and α-fetoprotein are usually abnormal in patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. α-Fetoprotein is most frequently abnormal and is elevated either alone or in conjunction with HCG in approximately 80% of patients, whereas elevation of HCG occurs in only 30 to 35% of patients. This pattern of marker elevation differs slightly from that seen in testicular cancer, where elevations of HCG and α-fetoprotein occur with nearly equal frequency and are seen in 50 to 70% of patients with metastatic tumor. As in mediastinal seminoma, elevation of serum lactic dehydrogenase is frequent, occurring in 80 to 90% of patients.

References

- Ringertz N, Lidholm SO. Mediastinal tumors and cysts. J Thorac Surg 1956;31:458-87.

- Wychulis AR, Payne WS, Clagett OT, Woolner LB. Surgical treatment of mediastinal tumors: a 40-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1971;62:379-92.

- LeRoux BT. Mediastinal teratoma. Thorax 1960;15:333-8.

- Lewis BD, Hurt RD, Payne WS, et al. Benign teratomas of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 86:727-31.

- Friedman NB. The comparative morphogenesis of extragenital and gonadal teratoid tumors. Cancer 1951; 4:265-76.

- Schlumberger HG. Teratoma of anterior mediastinum in group of military age: study of 16 cases and review of theories of genesis. Arch Pathol 1946;41:398-444.

- Azzopardi JG, Mostofi FK, Theiss EA. Lesions of testes observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. Am J Pathol 1961;38:207-25.

- Rather LJ, Gardiner WR, Frericks JB. Regression and maturation of primary testicular tumors with progressive growth of metastases: report of six new cases and review of literature. Stanford Med Bull 1954;12:12-25.

- Johnson DE, Laneri JP, Mountain CF, Luna M. Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Surgery 1973;73:85-90.

- Luna MA, Valenzuela-Tamariz J. Germ-cell tumors of the mediastinum, postmortem findings. Am J Clin Pathol 1976;65:450-4.

- Luna MA, Johnson DE. Postmortem findings in testicular tumors. In: Johnson DE, editor. Testicular tumors. New York: Medical Examination Publishing; 1975. p. 78-92.

- Willis RA. Borderland of embryology and pathology, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Butterworth; 1962. p. 442.

- Freidman NB. The function of the primordial germ cell in extragonadal tissues. Int J Androl 1987;10:43-9.

- Boyd DP, Midell AI. Mediastinal cysts and tumors: an analysis of 96 cases. Surg Clin North Am 1968;48:493-505.

- Hodge J, Aponte G, McLaughlin E. Primary mediastinal tumors. J Thorac Surg 1959;37:730-44.

- Collins DH, Pugh RCB. Classification and frequency of testicular tumors. Br J Urol 1984;36:1-11.

- Einhorn LH, Williams SD. Management of disseminated testicular cancer. In: Einhorn LH, editor. Testicular tumors: management and treatment. New York: Mason; 1980. p. 117-51.

- Motzer RJ, Rodriguez E, Reuter VE, et al. Molecular and cytogenetic studies in the diagnosis of patients with midline carcinomas of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:274-82.

- Motzer RJ, Rodriguez E, Reuter VE, et al. Genetic analysis as an aid in diagnosis for patients with poorly differentiated carcinomas of uncertain histologies. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:341-6.

- Greco FA, Vaughn WK, Hainsworth JD. Advanced poorly differentiated carcinoma of unknown primary site: recognition of a treatable syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:547-53.

- Fox RM, Woods RL, Tattersall MHN. Undifferentiated carcinoma in young men: the atypical teratoma syndrome. Lancet 1979;1:1316-8.

- Richardson RL, Schoumacher RA, Fer MF, et al. The unrecognized extragonadal germ cell cancer syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1981;94:181-6.

- Aliotta PJ, Castilla J, Englander LS, et al. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Histologic patterns of treatment failure at autopsy. Cancer 1988;62:982-4.

- Vugrin D, Martini N, Whitmore WF, Goldberg RB. VAB-3 combination chemotherapy in primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer Treat Rep 1982;66:1405-7.

- Einhorn L, Williams S, Loehrer P, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin dose intensity in advanced germ cell tumors. A Southeastern and Southwest Oncology Group protocol. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1990;9:132.

- Moran CA, Suster S. Primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum - I. Analysis of 322 cases with special emphasis on teratomatous lesions and a proposal for histopathologic classification and clinical staging. Cancer 1997:80:681-90.

- Polansky SM, Barwick KW, Ravin CE. Primary mediastinal seminoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1979;132:17-21.

- Jain KK, Bosl GJ, Bains MS, et al. The treatment of extra-gonadal seminoma. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:820-7.

- Knapp RH, Hurt RD, Payne WS, et al. Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985;89:82-9.

- Bagshaw MA, McLaughlin WT, Earle JD. Definitive radiotherapy of primary mediastinal seminoma. Am J Radiol Radiother Biophys 1969;105:86-94.

- Levitt RG, Husband JE, Glazer HS. CT of primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:73-8.

- Hainsworth JD, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, et al. Advanced extragonadal germ cell tumors. Successful treatment with combination chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med 1982;97:7-11.

- Israel A, Bosl GJ, Golbey RB, et al. The results of chemotherapy for extragonadal germ cell tumors in the cisplatin era: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience (1975 to 1982). J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1073-8.

- Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Selig DE, et al. Chemotherapy of extragonadal germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:316-25.

- Sickles EA, Belliveau RF, Wiernik PH. Primary mediastinal choriocarcinoma in the male. Cancer 1974;33:1196-203.

- Kay PH, Wells FC, Goldstraw P. A multidisciplinary approach to primary nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg 1987; 44:578-82.

- Nichols CR, Saxman S, Williams SD, et al. Primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors - a modern single institution experience. Cancer 1990;65:1641-6.

- Scheike D, Visfeldt J, Petersen B. Male breast cancer. 3. Breast carcinoma in association with the Klinefelter syndrome. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1973; 81:352-8.

- Curry WA, McKay CE, Richardson RL, Greco FA. Klinefelter's syndrome and mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Urol 1981;125:127-9.

- Turner AR, MacDonald RN. Mediastinal germ cell cancers in Klinefelter's syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1981;94:279.

- Nichols CR, Heerema NA, Palmer C, et al. Klinefelter's syndrome associated with mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:1290-4.

- Carroll PR, Whitmore WF Jr, Richardson M, et al. Testicular failure in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Cancer 1987;60:108-13.

- Hartmann JT, Fossa SD, Nichols CR, et al. Incidence of metachronous testicular cancer in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1733-8.

- Nichols CR, Hoffman R, Einhorn LH, et al. Hematologic malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Ann Intern Med 1985;102:603-9.

- DeMent SH, Eggleston JC, Spivak JL. Association between mediastinal germ cell tumors and hematologic malignancies: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1985;9:23-30.

- Hoekman K, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Egbers-Bogaards MA, et al. Acute leukemia following therapy for teratoma. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1984;20:501-2.

- Landanyi M, Roy I. Mediastinal germ cell tumor and histiocytosis. Hum Pathol 1988;19:586-90.

- Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, et al. Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1425-9.

- Sales LM, Vontz FK. Teratoma and di Guglielmo syndrome. South Med J 1970;63:448-50.

- Larsen M, Evans WK, Shepherd FA, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: possible origin from a mediastinal germ cell tumor. Cancer 1984;53:441-4.

- Orazi A, Neiman RS, Ulbright TM, et al. Hematopoietic precursor cells within the yolk sac tumor component are the source of secondary hematopoietic malignancies in patients with mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer 1993;71:3873-81.

- Chaganti RS, Landanyi M, Samaniego F. Leukemic differentiation of a mediastinal germ cell tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1989;1:83-7.

- Landanyi M, Samaniego F, Reuter VE, et al. Cytogenetic and immunohistochemical evidence for the germ cell origin of a subset of acute leukemias associated with mediastinal germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990;82:221-7.

- Hartmann JT, Nichols CR, Droz JP, et al. Hematologic disorders associated with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:54-61.

- Garnick MB, Griffin JD. Idiopathic thrombocytopenia in association with extragonadal germ cell cancer. Ann Intern Med 1983;98:926-7.

- Helman LJ, Ozols RF, Longo DL. Thrombocytopenia and extragonadal germ cell neoplasm. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:280.

- Lattes R. Thymoma and other tumors of thymus: analysis of 107 cases. Cancer 1962;15:1224-60.

- Martini N, Golbey RB, Hajdu SI, et al. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer 1974;33:763-9.

- Schantz A, Sewall W, Castleman B. Mediastinal germinoma. A study of 21 cases with an excellent prognosis. Cancer 1972;30:1189-94.

- Dulmet EM, Macchiarini P, Suc B, Verley JM. Germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: a 30-year experience. Cancer 1993;72:1894-901.

- Hurt RD, Bruckman JE, Farrow GM, et al. Primary anterior mediastinal seminoma. Cancer 1982;49:1658-63.

- Bush SE, Martinez A, Bagshaw MA. Primary mediastinal seminoma. Cancer 1981;48:1877-92.

- Loehrer PJ, Birch R, Williams SD, et al. Chemotherapy of metastatic seminoma. The Southeastern Cancer Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:1212-20.

- Bukowski RM, Wolf M, Kulander BG, et al. Alternating combination chemotherapy in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Cancer 1993;71:2631-8.

- Delgado FG, Tjulandin SA, Gavin AM. Long-term results of treatment in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors. Eur J Cancer 1993;29A:1002-5.

- Goss PE, Schwertfeger L, Blackstein ME, et al. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: a 14-year Toronto experience. Cancer 1994;73:1971-9.

- Mencel PJ, Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, et al. Advanced seminoma: treatment results, survival, and prognostic factors in 142 patients. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:120-6.

- Gerl A, Clemm C, Lamerz R, Wilmanns W. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy of primary extragonadal germ cell tumors: a single institution experience. Cancer 1996;77:526-32.

- Bokemeyer C, Droz JP, Horwich A, et al. Extragonadal seminoma: an international multicenter analysis of prognostic factors and long-term treatment outcome. Cancer 2001;91:1394-401.

- Peckham MJ, Horwich A, Hendry WF. Advanced seminoma: treatment with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy or carboplatin. Br J Cancer 1985;52:7-13.

- Schultz SM, Einhorn LH, Conces DJ, et al. Management of postchemotherapy residual mass in patients with advanced seminoma: Indiana University experience. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1497-503.

- Puc HS, Heelan R, Mazumdar M, et al. Management of residual mass in advanced seminoma: results and recommendations from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:454-60.

- Motzer R, Bosl G, Heclan R, et al. Residual mass: an indication for further therapy in patients with advanced seminoma following systemic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:1064-70.

- Williams SD, Birch R, Einhorn LH, et al. Treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1435-40.

- Cox JD. Primary malignant germinal tumors of the mediastinum. A study of 24 cases. Cancer 1975;36:1162-8.

- Funes HC, Mendez M, Alonso E, et al. Mediastinal germ cell tumors treated with cisplatin, bleomycin and vinblastine (PVB) [abstract]. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 1981;22:474.

- Fizazi K, Culine S, Droz JP, et al. Primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: results of modern therapy including cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:725-32.

- Einhorn LH. Testicular cancer as a model for a curable neoplasm. The Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award Lecture. Cancer Res 1981;41:3275-80.

- Toner GC, Geller NL, Lin S-Y, Bosl GJ. Extragonadal and poor risk nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: survival and prognostic features. Cancer 1991;67:2049-57.

- Kuzur ME, Cobleigh MA, Greco FA, et al. Endodermal sinus tumor of the mediastinum. Cancer 1982; 50:766-74.

- Chong CD, Logothetis CJ, von Eschenbach AC, et al. Successful treatment of pure endodermal sinus tumors in adult men. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:303-7.

- Loehrer PJ, Laner R, Roth BJ, et al. Salvage therapy in recurrent germ cell cancer: ifosfamide and cisplatin plus either vinblastine or etoposide. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:540-6.

- Saxman SB, Nichols CR, Einhorn LH. Salvage chemotherapy in patients with extragonadal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: the Indiana University experience. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:1390-3.

- Hartmann JT, Einhorn L, Nichols CR, et al. Second-line chemotherapy in patients with relapsed extragonadal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: results of an international multicenter analysis. J Clin Oncol 2001:19:1641-8.

- Ganjoo KN, Rieger KM, Kesler KA, et al. Results of modern therapy for patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Cancer 2000;88:1051-6.

- Fox EP, Weathers TD, Williams SD, et al. Outcome analysis for patients with persistent nonteratomatous germ cell tumor in post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissections. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1294-9.

- Motzer RJ, Gulati S, Crown JP, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow rescue for patients with refractory germ cell tumors: early intervention is better tolerated. Cancer 1992;69:550-6.

- Einhorn LH, Stender MJ, Williams SD. Phase II trial of gemcitabine in refractory germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:509-11.

- Motzer RJ, Bajorin DF, Schwartz LH, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel shows antitumor activity in patients with previously treated germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:2277-83.

- Hainsworth JD, Johnson DH, Greco FA. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy in the treatment of poorly differentiated carcinoma and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site: results of a twelve-year experience at a single institution. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:912-22.

- Hainsworth JD, Johnson DH, Greco FA. Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary site: a newly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:364-71.

- McKay CE, Hainsworth JD, Burris HA, et al. Treatment of metastatic poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with paclitaxel/carboplatin/etoposide (PCE): a Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network phase II trial [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2002;21:158a.