Lung Cancer: Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Elderly

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States for both men and women. In the United States, 80% of patients with lung cancer have non-small cell lung cancer, while the remaining 20% have small cell lung cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer is a “catch all” term for a group of cancers originating in the lung that includes adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. All of these diseases are treated in a similar fashion, and are therefore discussed under the general heading of non-small cell lung cancer. The average age at diagnosis of lung cancer is 68 years, which means that more than half of all patients with non-small cell lung cancer are older than 65 years of age and one-third are over 70 years old.

WHAT DOES “ELDERLY” MEAN?

Prior to making treatment recommendations, the oncologist must assess an individual patient’s ability to tolerate the various types of treatment that are available to treat cancer, including surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, used either alone or in combination with each other. Patient age must be considered because some treatments may not be tolerated as well by older patients as by younger individuals. In previous studies, the definition of an “elderly” patient has varied from 65 years of age or older to 75 years of age or older. A more functional definition of “elderly” has been proposed as follows:“when the health status of a patient begins to interfere with oncological (cancer) decision-making guidelines”(1). This definition also takes into account the fact that a patient’s other medical problems could interfere with treatment of the cancer. Age, by itself, does not generally prevent the use of the best available therapy. However, with increasing age comes a higher propensity for chronic illnesses that may impair a patient’s functional ability and alter his or her ability to tolerate aggressive anticancer treatment. Debility caused by the cancer or by other illnesses may change the balance between the potential risks and benefits of a specific treatment.

Another relevant issue is that although lung cancer is very common in elderly patients, most of the available data regarding the optimal treatment of lung cancer comes from clinical trials in which the vast majority of patients are significantly younger than 65 years of age. Few elderly patients are enrolled into clinical trials, perhaps due to the greater chance that they may have other medical problems that exclude them from a trial or due to potential bias on the part of their physicians or the elderly patients themselves against enrollment in trials studying investigational, and potentially more aggressive, therapies. It is only in the past 10 years that trials have been specifically designed to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of treatment in elderly patients, but even in clinical trials designed for patients 70 years of age or older, the average age of treated patients tends to be in the early 70s with few patients over the age of 80 participating in such trials.

CHOOSING TREATMENT

Two of the most important pieces of information needed to decide on the appropriate treatment for patients with non-small lung cancer are the stage of the disease and the performance status of the patient. Cancer staging is a way to describe the extent of the disease. It also helps the oncologist guide treatment decision-making and offer general information to the patient regarding overall prognosis. In non-small cell lung cancer, staging is done by looking at the size of the tumor, involvement of lymph nodes within the chest, and the presence of cancer spread to areas outside of the chest, such as the brain, liver, bones, or adrenal glands. Table 1 presents the most common staging system used by oncologists for patients with non-small cell lung cancer(2).

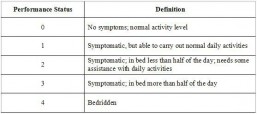

Table 1. International Staging System for Lung Cancer, 1997 Revision The performance status of a patient helps an oncologist define how the lung cancer or other medical problems are affecting the patient’s ability to function. The worse the performance status, the more likely it is that the patient will have significant complications during aggressive treatment. Table 2 presents one performance status scale commonly used by oncologists to gauge an individual patient’s level of daily functioning. Patients with non-small cell lung cancer and a performance status of 3 or 4 are usually not candidates for surgery or chemotherapy. In addition to evaluating general performance status, a careful assessment of heart function, lung function, and other chronic illnesses may be required before treatment recommendations can be made.

Table 1. International Staging System for Lung Cancer, 1997 Revision The performance status of a patient helps an oncologist define how the lung cancer or other medical problems are affecting the patient’s ability to function. The worse the performance status, the more likely it is that the patient will have significant complications during aggressive treatment. Table 2 presents one performance status scale commonly used by oncologists to gauge an individual patient’s level of daily functioning. Patients with non-small cell lung cancer and a performance status of 3 or 4 are usually not candidates for surgery or chemotherapy. In addition to evaluating general performance status, a careful assessment of heart function, lung function, and other chronic illnesses may be required before treatment recommendations can be made.

TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH STAGE I OR STAGE II DISEASE SURGERY

Stage I or II non-small cell lung cancer typically means that the cancer is confined to the lung and there is no or minimal lymph node involvement. The most effective treatment for patients with stage I or II disease is to surgically remove the cancer by cutting out all or part of the involved lung. Studies have shown that elderly patients with good lung and heart function and a good performance status can tolerate lung cancer surgery as well as younger patients with a similar chance for cure (3-7). Older patients may need to undergo a more rigorous evaluation of their heart and lung function prior to surgery to ensure that surgery can be performed safely and with an acceptable risk of long-term complications. For patients with stage I disease, 60-80% can be cured by surgical removal of the cancer. For those with stage II disease, 40-50% of patients can be cured by surgery. For more information on surgery, see the article in CancerNews titled “Lung Cancer: Who is a Candidate for Surgery?”

Table 2. Zubrod or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Scale

Table 2. Zubrod or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Scale

RADIATION THERAPY

Radiation therapy is the treatment of cancer by a beam of high energy x-rays directed at the part of the body affected by the cancer. Like surgery, it is a local treatment that only can kill cancer cells within the area being treated, not throughout the whole body. Some elderly patients may not be able to undergo surgical removal of stage I or II non-small cell lung cancer because of a significant medical problem, such as a recent heart attack or poor lung function due to emphysema. In these situations, radiation therapy targeted to the main lung tumor and to lymph nodes to which the cancer has spread may be the best treatment option for potential cure. However, the chance for cure in patients with stage I disease treated with radiation therapy is only 20-30%, significantly lower than that seen with surgery (8). For patients who can tolerate surgery and undergo complete removal of a stage I or II cancer, radiation therapy is not typically recommended because it has not been shown to improve the chance for cure and can cause potentially serious side-effects in patients with underlying lung disease.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy is a term that pertains to many different drugs, usually given through a vein, used to try to kill cancer cells wherever they might be in a patient’s body. Chemotherapy is not typically used as the sole treatment for stage I or II non-small cell lung cancer because by itself it cannot cure the disease. Sometimes it is used after surgery as adjuvant therapy (meaning “in addition to” the primary treatment, in this case surgery). In several recent clinical trials, chemotherapy has been shown to decrease the chance for cancer recurrence and improve the chance for cure in some patients who have undergone complete surgical removal of stage IB, II, or IIIA non-small cell lung cancer. All of these studies were randomized trials in which half of the enrolled patients received chemotherapy after surgical removal of the tumor and the other half received no further therapy.

The first of these adjuvant trials, called IALT, demonstrated a 5% decrease in cancer recurrence rate and a 4% improvement in survival in patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy compared to those receiving no further therapy after surgical removal of stage IB, II, or III non-small cell lung cancer (9). While the benefit of chemotherapy in this trial may seem small, a recurrence of the cancer is usually incurable, meaning that chemotherapy given after surgery can prevent some people from dying of the cancer. Importantly, patients over 75 years of age were not allowed to participate in this trial and the average age of patients enrolled was only 59 years. Therefore, it is not clear whether the benefit of chemotherapy seen in this trial would also occur in an older population of patients. The second of these trials, called JBR.10, demonstrated a 15% improvement in survival in patients treated with the chemotherapy combination of cisplatin plus vinorelbine compared to those receiving no further therapy after surgical removal of stage IB or II non-small cell lung cancer (10). The third recent adjuvant chemotherapy trial, called CALGB 9633, demonstrated a 12% improvement in survival in patients treated with carboplatin plus paclitaxel compared to those receiving no further therapy after surgical removal of stage IB non-small cell lung cancer (11). Although the JBR.10 and CALGB 9633 trials did not limit the age of potential participants, the average age of patients enrolled in both of these trials was 61 years and few patients were over 75 years of age. The most recent of the adjuvant trials, called the ANITA trial, demonstrated an 8% improvement in survival in patients treated with cisplatin plus vinorelbine compared to those receiving no further therapy after surgical removal of stage IB, II, or IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (11). As in the first trial mentioned above, patients over the age of 75 years were not allowed to participate in the ANITA trial.

Overall, adjuvant chemotherapy is now recommended for patients who have undergone complete removal of stage IB, II, or III non-small cell lung cancer and have recovered from surgery within two months without significant complications. Clearly, the oncologist must carefully evaluate every patient to ensure that the potential benefits of chemotherapy outweigh the risk of serious side-effects of treatment. If adjuvant chemotherapy is given, the chemotherapy should consist of four cycles of cisplatin or carboplatin in combination with another chemotherapy agent, usually vinorelbine, paclitaxel, or etoposide. While age alone should not be a deterrent to receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, the oncologist must keep in mind that very few elderly patients were involved in the clinical trials that determined the benefits of this treatment.