Lung Cancer: Who is a Candidate for Surgery?

Lung Cancer: Who is a Candidate for Surgery?: An Emerging Role for PET Scanning

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States for both men and women and continues to have a five-year survival rate of less than 10%. Currently, complete surgical resection remains the best hope for cure. However, not all patients with lung cancer are candidates for surgical resection. This article describes the process used in selecting patients who are eligible for lung cancer resection. After determining that lung cancer is present, it is important to assess the resectability of the tumor as well as the suitability of the patient for an operation evaluating the histological type of cancer, the degree of invasion, and the patient’s other medical conditions.

TUMOR RESECTABILITY

Resectability of the tumor depends on the type of cancer as well as the degree of invasion which is determined by characteristics of the primary tumor as well as the presence of lymph node or distant metastases.

Type of Cancer

If the lesion is accessible, bronchoscopy, inserting a scope to inspect the airway, can provide tissue to make a diagnosis.

In addition, bronchial washing, brushing, and transbronchial needle aspiration can aid in establishing the diagnosis. In lesions that cannot be seen, bronchoalveolar lavage, washing the airways with saline, can provide cells to be examined by a cytopathologist. An alternative approach, especially for peripheral lesions, is the use of percutaneous computed tomography (CT)-guided needle biopsy.

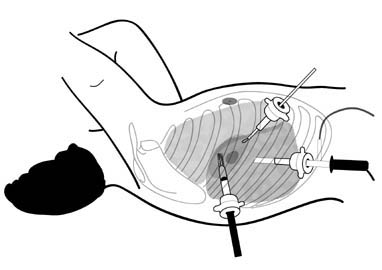

Possible complications include pneumothorax, the leakage of air between the lung and the chest wall, which is treated conservatively in the majority of cases. If present, pleural fluid, surrounding the lung, can be sampled for cancer cells, or a biopsy of the pleura, the lining surrounding the lung, can be performed. When other studies are non-diagnostic, video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS), a minimally invasive surgical technique inserting a scope in the space between the lung and the chest wall, is successful in making the diagnosis in 90% of cases due to the ability to visualize suspicious areas for biopsy (Figure 1) (1).

For small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy and radiation are generally the main treatment modalities since the majority of patients have metastatic disease at the time of presentation. Surgery can be offered for limited T1 or T2 (Table 1) lesions without lymph node involvement (Stage I) followed by chemotherapy although less than 5% of patients present at this stage (2).

Figure 1. Video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection of a lung nodule.

Figure 1. Video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection of a lung nodule.

For small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy and radiation are generally the main treatment modalities since the majority of patients have metastatic disease at the time of presentation. Surgery can be offered for limited T1 or T2 (Table 1) lesions without lymph node involvement (Stage I) followed by chemotherapy although less than 5% of patients present at this stage (2).

Patients with mixed small and non-small cell histology may also benefit from resection after chemotherapy. However, before surgery is considered, patients should undergo complete staging with CT (including the head), positron emission tomography (PET), and mediastinoscopy, placing a scope through a neck incision to examine the lymph nodes between the lungs, if needed. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, bronchoalveolar, and large cell carcinoma, is generally more amenable to resection and is present in 80% of the cases of lung cancer in North America (3).

Patients with mixed small and non-small cell histology may also benefit from resection after chemotherapy. However, before surgery is considered, patients should undergo complete staging with CT (including the head), positron emission tomography (PET), and mediastinoscopy, placing a scope through a neck incision to examine the lymph nodes between the lungs, if needed. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, bronchoalveolar, and large cell carcinoma, is generally more amenable to resection and is present in 80% of the cases of lung cancer in North America (3).

Degree of Invasion

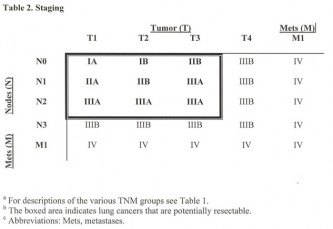

The optimal treatment and prognosis of NSCLC is related to the pathologic stage at presentation which is determined using the TNM system (Table 1) evaluating characteristics of the primary tumor (T), whether there has been invasion of lymph nodes (N), and the presence of distant metastases (M). The true stage of the tumor is not always obvious at the time of diagnosis and is often higher than initially thought. TNM staging of NSCLC allows the clinician to estimate a patient’s overall survival. Staging has become even more important with the increasing use of preoperative chemotherapy and radiation for locoregionally advanced tumors (Stage IIIA).

In general, stage I (confined to the lung without nodal or distant metastases), II (involvement of only lymph nodes within the lung or the hilum, the area where blood vessels enter the lung, on the same side as the tumor), and IIIA (involvement of nodes in the mediastinum, the area between the lungs, on the same side as the tumor) (Table 2) are considered potentially resectable for cure with a survival following complete resection of 76%, 47%, and 26-56% (4). Stage IIIB (involvement of the mediastinal organs, between the lungs, or lymph node metastases on the side opposite from the tumor) and IV (distant metastases) are generally considered surgically incurable although a “gray zone” exists with some advocating resection of limited N2 disease (involvement of mediastinal nodes on the same side as the tumor), stage IIIB without N2 disease or with a squamous cell histology, and stage IV with a solitary brain metastasis. To be curative, all areas invaded by cancer including involved areas of the diaphragm, pericardium, chest wall, and lymph nodes must be resected.

In general, stage I (confined to the lung without nodal or distant metastases), II (involvement of only lymph nodes within the lung or the hilum, the area where blood vessels enter the lung, on the same side as the tumor), and IIIA (involvement of nodes in the mediastinum, the area between the lungs, on the same side as the tumor) (Table 2) are considered potentially resectable for cure with a survival following complete resection of 76%, 47%, and 26-56% (4). Stage IIIB (involvement of the mediastinal organs, between the lungs, or lymph node metastases on the side opposite from the tumor) and IV (distant metastases) are generally considered surgically incurable although a “gray zone” exists with some advocating resection of limited N2 disease (involvement of mediastinal nodes on the same side as the tumor), stage IIIB without N2 disease or with a squamous cell histology, and stage IV with a solitary brain metastasis. To be curative, all areas invaded by cancer including involved areas of the diaphragm, pericardium, chest wall, and lymph nodes must be resected.

A number of complementary approaches are useful in staging lung cancer including CT, PET, bronchoscopy, and mediastinoscopy. The selection and interpretation of imaging studies and procedures is important in determining the optimal treatment. The goal of staging studies is to identify patients who might be potential surgical candidates since early stage lung cancer is potentially curable by surgical resection. Surgery can also be used to provide local control in advanced disease.

All patients, except those with small peripheral tumors less than 2 cm and no evidence of N2 nodal disease on CT or PET, should undergo mediastinoscopy. Patients with suspected lung cancer should undergo CT of the chest and abdomen and if available, an FDG-PET (fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography) to evaluate for distant metastases which occur in 50% of patients with NSCLC. Suspicious lesions are biopsied to avoid false positive results. Patients with neurological symptoms should undergo a head CT or MRI to evaluate for metastases. A bone scan may also be useful if metastases are suspected after a thorough history and physical examination and evaluation of laboratory studies such as alkaline phosphatase and calcium. If the clinical evaluation is negative, the likelihood of finding metastases appears to be low.