Osteoporosis drug stops growth of breast cancer cells, even in resistant tumors

A drug approved in Europe to treat osteoporosis has now been shown to stop the growth of breast cancer cells, even in cancers that have become resistant to current targeted therapies, according to a Duke Cancer Institute study.

The findings, presented June 15, 2013, at the annual Endocrine Society meeting in San Francisco, indicate that the drug bazedoxifene packs a powerful one-two punch that not only prevents estrogen from fueling breast cancer cell growth, but also flags the estrogen receptor for destruction.

“We found bazedoxifene binds to the estrogen receptor and interferes with its activity, but the surprising thing we then found was that it also degrades the receptor; it gets rid of it,” said senior author Donald McDonnell, PhD, chair of Duke’s Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology.

In animal and cell culture studies, the drug inhibited growth both in estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells and in cells that had developed resistance to the anti-estrogen tamoxifen and/or to the aromatase inhibitors, two of the most widely used types of drugs to prevent and treat estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Currently, if breast cancer cells develop resistance to these therapies, patients are usually treated with toxic chemotherapy agents that have significant side effects.

Bazedoxifene is a pill that, like tamoxifen, belongs to a class of drugs known as specific estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). These drugs are distinguished by their ability to behave like estrogen in some tissues, while significantly blocking estrogen action in other tissues. But unlike tamoxifen, bazedoxifene has some of the properties of a newer group of drugs, known as selective estrogen receptor degraders, or SERDs, which can target the estrogen receptor for destruction.

“Because the drug is removing the estrogen receptor as a target by degradation, it is less likely the cancer cell can develop a resistance mechanism because you are removing the target,” said lead author Suzanne Wardell, PhD, a research scientist working in McDonnell’s lab.

Many investigators had assumed that once breast cancer cells developed resistance to tamoxifen, they would be resistant to all drugs that target the estrogen receptor, McDonnell explained.

Many investigators had assumed that once breast cancer cells developed resistance to tamoxifen, they would be resistant to all drugs that target the estrogen receptor, McDonnell explained.

“We discovered that the estrogen receptor is still a good target, even after it resistance to tamoxifen has developed,” he said.

Breast Cancer Stem Cell Research

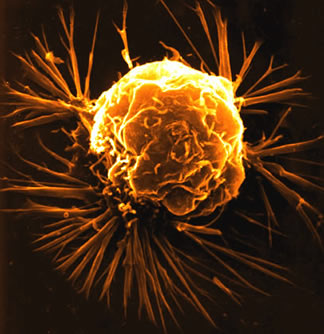

Breast cancer stem cells were discovered in 2003 by scientists at the U-M Comprehensive Cancer Center

In the fight against breast cancer, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that, since 1990, there has been a steady decline in the death rate from breast cancer. Earlier detection and better treatments are bringing hope to people with both early and advanced disease.

The bad news is that more than 40,000 people die from breast cancer every year in the United States alone. It is still the second-leading cause of deaths from cancer in women. The survival rate for those with advanced, metastatic breast cancer has not changed significantly for decades. In spite of more effective therapies, many patients still experience recurrences of breast cancer after treatment.

We believe that conventional therapies for advanced breast cancer are limited because they target the wrong cells. These therapies were designed to shrink cancers by killing all the cells in a tumor. We believe therapies could be more effective, and cause fewer side effects, if they were aimed specifically at a small group of cells within the tumor called cancer stem cells.

Breast cancer stem cells - the first to be identified in a solid tumor - were discovered in 2003 by scientists at the U-M Comprehensive Cancer Center. U-M scientists found that just a few cancer stem cells are responsible for the growth and spread of breast cancer. Unless the cancer stem cells are destroyed, the tumor is likely to come back and spread malignant cells to other parts of the body, a process called metastasis.

Because cancer stem cells are resistant to traditional chemotherapy and radiation, we need new treatments that can be targeted directly at these deadly cells. U-M Cancer Center scientists are studying breast cancer stem cells to learn more about them and to determine the type of therapy most likely to destroy the cells. The world’s first clinical study of a treatment targeted at stem cells in breast cancer was conducted at the U-M Cancer Center and other clinical studies are currently in development.

The investigators tested a variety of breast cancer cell types, including tamoxifen-sensitive cells that are resistant to the drug lapatinib, another targeted therapy that is used to treat patients with advanced breast cancer whose tumors contain the mutant HER2 gene. These cells had previously been shown to reactivate estrogen signaling in order to acquire drug resistance. In this cell type, bazedoxifene also potently inhibited cell growth.

Paradoxically, in bone tissue, bazedoxifene mimics the action of estrogen, helping protect it from destruction. Because bazedoxifene has already undergone safety and efficacy studies as a treatment for osteoporosis, it may be a viable near-term option for patients with advanced breast cancer whose tumors have become resistant to other treatment options, Wardell reported. In clinical trials, the most often reported side effect was hot flashes in the bazedoxifene treatment groups.

Paradoxically, in bone tissue, bazedoxifene mimics the action of estrogen, helping protect it from destruction. Because bazedoxifene has already undergone safety and efficacy studies as a treatment for osteoporosis, it may be a viable near-term option for patients with advanced breast cancer whose tumors have become resistant to other treatment options, Wardell reported. In clinical trials, the most often reported side effect was hot flashes in the bazedoxifene treatment groups.

Do breast cancer stem cells cause metastasis?

There are many factors that trigger metastasis in cancer and scientists don’t yet understand how they all work. But we do know that stem cells are involved in the process. Recent research by U-M Cancer Center scientists found that cells from tumors with a higher percentage of cancer stem cells were more likely to break away and spread.

Advances in mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening for breast cancer have made it possible for doctors to see breast tumors when they are very small. When physicians can diagnose and treat breast cancer early, they often can remove the tumor with surgery and prevent a recurrence.

Once malignant cells leave the primary breast tumor and migrate to other parts of the body, however, treatment is more difficult. Chemotherapy and radiation will kill most malignant cells and shrink the tumor, but the cancer often comes back, because these therapies don’t kill the stem cells. In addition, cancer stem cells drive metastasis - the tendency of malignant cells to spread throughout the body and form new tumors. Metastatic cancer is often what causes the death of women with advanced breast cancer.

To cure metastatic breast cancer, U-M scientists believe you must eliminate the cancer stem cells. Chemotherapy and radiation alone cannot do that.

###

The study was funded by a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, maker of bazedoxifene.

In addition to Wardell and McDonnell, Erik Nelson and Christina Chao of the Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University School of Medicine, contributed to the research.

###

Rachel Harrison

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

919-419-5069

Duke University Medical Center