Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian Cancer

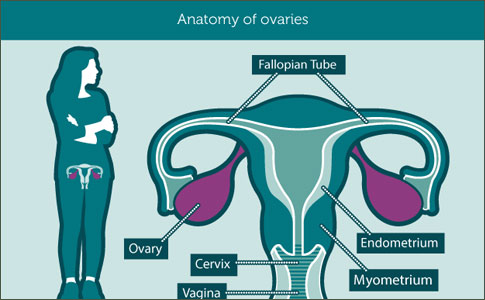

The ovaries are part of the female reproductive system. They produce a woman's eggs and female hormones. Each ovary is about the size and shape of an almond.

Cancer of the ovary is not common, but it causes more deaths than other female reproductive cancers. The sooner ovarian cancer is found and treated, the better your chance for recovery. But ovarian cancer is hard to detect early. Women with ovarian cancer may have no symptoms or just mild symptoms until the disease is in an advanced stage. Then it is hard to treat. Symptoms may include

- A heavy feeling in the pelvis

- Pain in the lower abdomen

- Bleeding from the vagina

- Weight gain or loss

- Abnormal periods

- Unexplained back pain that gets worse

- Gas, nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite

To diagnose ovarian cancer, doctors do one or more tests. They include a physical exam, a pelvic exam, lab tests, ultrasound, or a biopsy. Treatment is usually surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death among gynecologic malignancies. In 1999, there were 25,200 new ovarian cancers diagnosed and 14,000 deaths from this disease. Women have a 1 in 70 lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer, and 1 in 100 will die of this disease. More than 48% of ovarian cancers occur in women over the age of 65. Age-adjusted incidence rates increase as age advances. For women under 40, the incidence is 1.4 per 100,000 women; the incidence is between 40 and 50 per 100,000 for women over age 60, and peaks at 57.0 per 100,000 for women 70 to 74 years old (Figure 37.3). Most ovarian cancers are diagnosed at advanced stage, with extensive intraabdominal spread present at the time of initial diagnosis.

Many risk factors have been identified for ovarian cancer. The best documented of these is the relationship between the number of lifetime ovulatory cycles and ovarian cancer risk. Events or conditions that suppress ovulation protect women against this malignancy. Thus, multiparity, oral contraceptive use, and a history of breastfeeding are protective. Conversely, women who are nulliparous or who undergo a late menopause are at increased risk. Women who have undergone ovulation induction therapy for infertility may have a higher risk, but this has not yet been firmly established. High dietary fat consumption, use of talc in perineal regions, and mumps infections before menarche have also been implicated as factors that elevate ovarian cancer risk.

Sex cord/stromal tumors arise from mesenchymal tissues and account for about 5% of ovarian cancers. These tumors may occur at any age; subtypes consist of granulosa cell, thecoma, fibroma, and Sertoli-Leydig histologies. Germ cell tumors make up another category. They typically afflict children and adolescents and are relatively rare in postmenopausal women. These tumors account for approximately 15% to 20% of ovarian cancers. Ovarian metastases may arise from other primary cancers such as breast, endometrial, lymphoma, colon, and stomach and may present with signs and symptoms similar to de novo ovarian cancer. Because the majority of ovarian cancers in the geriatric population are of epithelial origin, our discussion focuses on this category. Other issues specifically related to the care of elderly ovarian cancer patients are addressed next.

Ovarian cancer often has an insidious onset with nonspecific symptoms, which often results in a delay in diagnosis. Gastrointestinal symptoms are common including dyspepsia, nausea, early satiety, altered bowel habits, eructation, abdominal discomfort, pain, and distension. Patients are often initially misdiagnosed with stress, depression, irritable bowel syndrome, or gastritis. The correct diagnosis of ovarian cancer requires a high index of suspicion.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is one of the most treatable solid tumors, as the majority will respond temporarily to surgery and cytotoxic agents.

Ovarian Cancer Risk Factors

Ovarian Cancer can be extremely difficult to detect through a routine pelvic exam, and especially difficult during its early stages. This is why keeping an eye out for any potential risk factors is currently the most effective way we have of combatting ovarian cancer and treating it early.

While we cannot accurately predict whether or not an individual will develop ovarian cancer, there are several major risk factors that increase a woman's chance of being diagnosed at some point in her lifetime.

PERSONAL HISTORY:

Those previously diagnosed with breast, colon and/or rectal cancer before the age of 40 are at a higher risk of contracting ovarian cancer.

OVER 55:

Women over the age of 55 are at a higher risk for ovarian cancer.

NEVER PREGNANT:

Women who have never been pregnant and are over the age of 55 are also at a higher risk for ovarian cancer.

HORMONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY:

Studies have suggested that women who have taken estrogen for 10+ years without an accompanying progesterone treatment are also at risk.

FAMILY HISTORY OF CANCER:

If your mother, daughter or sister has been diagnosed with either ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer, then you are at a significantly higher risk of being diagnosed as well. This also includes a history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch II), those with male relatives who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and a family history of mutation in the BRCA gene (a gene responsible for suppressing tumors).

FAMILY OVARIAN CANCER REGISTRY:

Because of this strong correlation between family history and ovarian cancer, the Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry was established. This national computer tracking system stores data compiled from women and their family members nationwide who have a family history of ovarian cancer. With this information, researchers hope to identify new genes associated with ovarian cancer in order to improve genetic and psychosocial counseling for these patients and also evaluate lifestyle choices that may reduce ovarian cancer risk among this population.

Women over the age of 18 with a family history of ovarian cancer are encouraged to join the registry.

The ovaries are part of the female reproductive system. They produce a woman's eggs and female hormones. Each ovary is about the size and shape of an almond.

Cancer of the ovary is not common, but it causes more deaths than other female reproductive cancers. The sooner ovarian cancer is found and treated, the better your chance for recovery. But ovarian cancer is hard to detect early. Women with ovarian cancer may have no symptoms or just mild symptoms until the disease is in an advanced stage. Then it is hard to treat. Symptoms may include

- A heavy feeling in the pelvis

- Pain in the lower abdomen

- Bleeding from the vagina

- Weight gain or loss

- Abnormal periods

- Unexplained back pain that gets worse

- Gas, nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite

To diagnose ovarian cancer, doctors do one or more tests. They include a physical exam, a pelvic exam, lab tests, ultrasound, or a biopsy. Treatment is usually surgery followed by chemotherapy.

A carefully detailed history and physical examination are essential. Symptoms, family history, and risk factors should be assessed. Physical examination should include meticulous abdominal, pelvic, and lymph node examinations. Omission of the pelvic exam at the first visit is an important factor associated with delay of diagnosis. Examination frequently reveals a significant abdominopelvic mass accompanied by ascites. Radiographic studies are sometimes useful in securing the diagnosis and triaging patients for appropriate treatment. Ultrasound can help differentiate benign from malignant lesions. Benign tumors often appear as simple cysts under 10 cm in diameter with septations less than 3 mm thick. Malignant lesions often are complex with solid and cystic components or are completely solid. Other malignant features include bilaterality, multiple septations greater than 3 mm, papillations, mural nodules, excrescences, and ascites. Doppler flow studies of malignant tumors show increased vascularity, enhanced blood flow, and decreased blood flow resistance. Computed tomography (CT) scans may be helpful, especially in the evaluation of retroperitoneal structures and the upper abdomen. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is expensive and thus far unproven in the evaluation of the adnexa. Barium enema is useful in cases where gastrointestinal symptoms suggestive of a colonic neoplasia are present. Abdominal plain films are beneficial for demonstrating small bowel obstruction in symptomatic patients. In cases of undiagnosed abdominopelvic masses, radiographic studies cannot replace surgical exploration for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Standard laboratory studies include complete blood count, electrolyte screen, and BUN-creatinine. Liver function analysis and coagulation panels are not usually informative in the absence of symptoms. The tumor marker CA 125 may be useful in the diagnosis and therapy of ovarian cancer. If serum CA 125 is elevated in postmenopausal women with a pelvic mass, cancer should be strongly suspected. However, there are many other causes of elevated CA 125,and this test should not be considered a definitive verification of the presence or absence of cancer. CA 125 is most helpful for monitoring disease status (tumor burden) during therapy. Paracentesis for analysis of ascitic fluid for diagnosis should be avoided. Risks of this procedure are (1) rupture of a cyst, which could release cancer cells or viscous mucoid material; (2) seeding of the needle tract with tumor; and (3) false reassurance may be acquired if cytology studies prove to be falsely negative. However, if the patient is experiencing intolerable symptoms, such as dyspnea due to ascites, a therapeutic paracentesis may be indicated.

What is ovarian cancer?

The term "ovarian cancer" includes several different types of cancer that all arise from cells of the ovary. Most commonly, tumors arise from the epithelium, or lining cells, of the ovary. These include epithelial ovarian (from the cells on the surface of the ovary), fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal (the lining inside the abdomen that coats many abdominal structures) cancer. These are all considered to be one disease process. There is also an entity called borderline ovarian tumors that have the microscopic appearance of a cancer, but tend not to spread much.

However, there are also less common forms of ovarian cancer that come from within the ovary itself, including germ cell tumors and sex cord-stromal tumors. All of these diseases will be discussed, as well as their treatment.

Epithelial ovarian cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for a majority of all ovarian cancers. It is generally thought of as one of three types of cancer that include ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer that all behave, and are treated the same way, depending on the type of cell that causes the cancer. The four most common cell types of epithelial ovarian cancer are serous, mucinous, clear cell, and endometrioid. These cancers arise due to DNA changes in cells that lead to the development of cancer. Serous cell type is the most common variety. It is now thought that many of these cancers actually come from the lining in the fallopian tube, and fewer of them from the cells on the surface of the ovary, or the peritoneum. However, it is often hard to identify the sources of these cancers when they present at advanced stages, which is very common.

Borderline ovarian tumors

Borderline ovarian tumors account for a small percentage of epithelial ovarian cancers. They are most often serous or mucinous cell types. They often have large masses, but they only rarely metastasize, that is, spread to other areas. Often, removal of the tumor, even at more advanced stages, can be a cure.

Germ cell ovarian cancers

Germ cells tumors arise from the reproductive cells of the ovary. These are uncommon. They include dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumors, embryonal carcinomas, polyembryomas, non-gestational choriocarcinomas, immature teratomas, and mixed germ cell tumors. They tend to occur more often in younger-aged women.

Stromal ovarian cancers

Another category of ovarian tumor is the sex cord-stromal tumors. These arise from supporting tissues within the ovary itself. As with germ cell tumors, these are uncommon. These cancers come from various types of cells within the ovary. They are much less common than the epithelial tumors. These include granulosa-stromal tumors and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors.

Signs & Symptoms

Not all women who develop ovarian cancer have a family history of the disease or any other known risk factors beyond advanced age. For these women, physical symptoms may be the only indicator that cancer is present. These symptoms are often overlooked or get mistaken for common illness, so the disease may go undetected until it has progressed beyond treatment.

If the following symptoms are experienced for more than two weeks, a woman should consult a physician:

- bloating or sudden weight loss

- pelvic or abdominal pain

- urinary frequency

- indigestion or feeling full quickly

- pelvic pressure

- abnormal or post-menopausal bleeding

Spread of ovarian cancer occurs by capsular invasion, peritoneal seeding and lymphatic infiltration. Peritoneal spread is the most common pattern and includes most peritoneal surfaces with frequent involvement of the omentum and diaphragm. Carcinoma of the uterus and cervix usually disseminate through pelvic lymphatics, whereas ovarian cancer drains to the para-aortic nodal tissue. Distant spread to intrathoracic regions or liver parenchyma may occur when malignant cells are transported via hematogenous routes. Extraovarian spread worsens prognosis. Another prognostic factor is tumor grade, which is usually more important than histologic subtype when forecasting outcome for women with early-stage ovarian epithelial cancers.

Staging of ovarian cancer employs a surgicopathologic system and is outlined in Table 37.2. Surgical staging is best accomplished by a gynecologic oncologist. Patients usually undergo preoperative antibiotic and mechanical bowel preparation. Exploratory laparotomy, comprehensive abdominal exploration, hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, omentectomy, and tumor debulking are performed. Peritoneal washings or ascites fluid is obtained for cytology. Random peritoneal or lymph node biopsies are performed in apparent early-stage cases to uncover occult microscopic tumor foci and document their locations. Pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissections are completed to document extent of tumor spread or to "debulk" the cancer. Bowel surgery is performed in appropriate cases to relieve obstruction or to reduce tumor volume. Surgical cytoreduction is performed to remove macroscopic tumor deposits because prognosis is directly related to the volume of residual disease before the initiation of adjuvant therapy. Bristow et al. demonstrated that even patients with stage IV disease benefited from aggressive cytoreduction. Median survival was 50 months for patients in whom both extra- and intrahepatic optimal cytoreduction had been accomplished versus only 7 months for patients who were suboptimally debulked. The full extent of tumor spread and amount of residual disease is documented so that appropriate therapeutic decisions can be made. Clearly surgical judgement is necessary to achieve optimal surgical and medical outcome, especially in elderly women who may have underlying medical problems.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Carcinoma of the Fallopian Tube

Uterine Cancer

Cervix Cancer

Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia

Patients with stage IA grade 1 epithelial ovarian cancer have such an excellent prognosis that postoperative adjuvant therapy is unnecessary. For those with more advanced cancers, postoperative treatment usually consists of six courses of platinum-based multiagent chemotherapy, usually cisplatin or carboplatin combined with paclitaxel. Paclitaxel and platinum-based therapy has been demonstrated in prospective randomized clinical trials to improve progression-free survival and overall survival for patients with advanced suboptimally debulked ovarian cancer. Carboplatin is just as efficacious as cisplatin and is associated with an improved adverse effect profile. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is also under investigation, and currently clinical trials are evaluating intravenous versus intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel for patients with optimally debulked stage III ovarian cancer. Novel therapeutic agents (such as antiangiogenic agents and gene therapies) are currently being evaluated in the treatment of ovarian cancer in clinical trials. Herceptin, anti-Her2neu antibody, is available to patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer who overexpress Her2neu.

Chemotherapeutic treatment spawns many side effects; elderly women particularly have an elevated risk of complications with some regimens. Cisplatin causes nausea, irreversible renal damage, and peripheral neuropathy (which is the dose-limiting toxicity). Administration of cisplatin requires extensive hydration and antiemetic therapy but can be safely used in the elderly. Carboplatin differs from its congener, cisplatin, in that it is much less emetogenic, nephrotoxic, and neurotoxic. Debilitated patients tolerate carboplatin therapy better than cisplatin treatment, owing to different toxicity profiles of these agents. Carboplatin is better tolerated by the elderly because it does not cause renal injury or nausea. Furthermore, because aggressive hydration is not required, carboplatin administration is less likely to exacerbate congestive heart failure or cause other side effects related to volume overload. The predominant side effects of paclitaxel are neutropenia and alopecia. Age alone is an insufficient criterion to alter the dose of either carboplatin or paclitaxel.

Radiation therapy (RT) has a limited role in treatment of ovarian cancer. Intraperitoneal P has sometimes been used to treat stage IC disease or for patients with persistent microscopic tumor deposits after chemotherapy. However, there are conflicting data regarding the efficacy of P therapy, and one study has even demonstrated that cisplatin significantly prevented relapse in stage IC patients compared to P therapy.

External beam radiation therapy is sometimes useful for local control of sizable tumor foci, or residual disease, or for treatment of extremely poor surgical candidates. Treatment of the entire peritoneal cavity with teletherapy with curative intent is impractical in most cases. However, lower-dose whole abdominal radiation may be employed in selected cases to control small-volume disease.

Survival of patients treated for ovarian cancer varies according to the stage of their disease. Five-year survival for women with epithelial ovarian cancer has improved and is as follows: stage I, 93%; stage II, 70%, stage III, 37%; stage IV, 25%. Survival in ovarian cancer patients is influenced by age. Multivariate analysis has revealed age to be an independent predictor of outcome. Overall, 5-year survival for elderly women over the age of 75is only 20%, compared to 70% for women under 45 years of age. This trend toward decreasing survival with advancing age holds true for patients with the same stage of ovarian cancer, even when adjustments for life expectancy are included. Older women are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage disease. Older women are also less likely to undergo complete surgical staging, extensive debulking, or receive multimodality therapy because of overriding comorbities. Bulky residual disease often remains after surgery due to the patient's otherwise poor health or because of limited experience of the surgeon in managing ovarian cancer patients. More than 40% of women 85years or older, according to a review of hospital records, did not receive any definitive therapy. Older women with ovarian cancer, in general, are treated less aggressively than their younger counterparts. Optimal therapy should not be withheld in elderly patients unless there are overriding medical contraindications.

Analysis of outcomes for patients involved with six randomized Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trials revealed that those over age 69 had poorer survival rates than younger women, even after correcting for stage, residual disease, and performance status. A retrospective case-control investigation has confirmed this finding. Other studies have shown that more conservative surgery and less aggressive adjuvant therapy are contributing factors that may lead to decreased survival in elderly patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, which was demonstrated to be due, in part, to these women receiving their care from obstetrician-gynecologists, general surgeons, and other nononcologists who persuaded them not to seek aggressive treatments. This bias against elderly women has been shown in another report documenting decreased specialist referral and use of physician influence to dissuade these cancer victims from obtaining optimum therapy. Thus, although advanced age presages a poorer prognosis, in appropriate candidates maximal surgical debulking and aggressive chemotherapy may partially mollify the effect of age.

Follow-up involves serial physical and pelvic examinations, CA 125 levels, and sometimes CT imaging. Today, "second-look" surgery is infrequently performed after initial chemotherapy to determine the status of the tumor, that is, whether microscopic or grossly evident foci exist. Although somewhat controversial, and with no evidence that this surgery improves overall survival, this procedure is generally limited to those participating in research protocols to assess the effectiveness of new treatment modalities. About 55% of patients who are clinically free of disease will have a positive (i.e., persistent tumor) second-look operation. Debate regarding second-look operation exists because of its fallibility in predicting survival. There is a 25%to 45% recurrence rate after a negative second-look procedure, and some argue that the information gained does not justify the expense and morbidity of the surgery.

Recurrence risk is increased with advanced-stage disease, high tumor grade, and large tumor volume. A number of strategies may be employed to control tumor recurrences, although most are aimed at palliation rather than "cure." Treatment with secondary surgical debulking, multiagent chemotherapy, radiation therapy, biologic response modifiers, or chemotherapy with monoclonal antibody-directed agents, intraperitoneal instillation, or systemic administration with experimental compounds have all been utilized. Therapy must be individualized based upon the site(s) of recurrence, the biology of the tumor, the patient's performance status, her medical comorbidities, and her wishes regarding how aggressively she wants the cancer treated.

Refractory cancer carries with it a very poor prognosis. Death usually occurs within 18 to 36 months as the cancer propagates and sprawls out on the splanchnic bed, causing bowel obstruction, nausea, and vomiting. Sepsis often follows bowel or ureteral obstruction. Severe electrolyte abnormalities may result from nutritional deficiencies, renal dysfunction following cisplatin treatment, and accumulation of massive peritoneal or pleural effusions. Decisions regarding management of persistent, progressive disease must be made with care and with the participation of the patient and her family. Relevant issues include support with total parenteral nutrition (which often can be administered at home by the patient or a family member), medical or surgical relief of bowel obstruction, intravenous hydration or antibiotics, hospice care, and pain management. It is imperative that maintaining quality of life and assuagement of pain be goals of therapy.

Epithelial ovarian cancer is not generally considered an estrogen-dependent neoplasia and, therefore, hormonal replacement therapy is not contraindicated. In fact, estrogen may augment the patient's quality of life and be an important part of her treatment.