Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Testicular Cancer

Testicular Cancer

Germ cell tumors of the testis are the most common cancer in young men between the ages of 15 and 35 years. Before 1970, the young man with recurrent testicular cancer following orchiectomy was destined to have rapid progression and death from disseminated disease. With the development of sophisticated high-voltage radiation therapy technology and the application of aggressive multiagent chemotherapy since the early 1970s, this cancer is routinely cured in young men entering the most productive phase of life. Consequently, the internist caring for the testicular cancer patient in whom durable remission and long-term survival are anticipated must recognize the impact of the disease and its therapy on fertility, employability, insurability, and delayed morbidity. In 1997, an estimated 7200 new cases of testis cancer will be diagnosed, yet only 350 deaths from the disease are expected. Testicular cancer is infrequent, occurring with an incidence of approximately 2 per 100,000 males. The incidence has been rising in white males while remaining stable in black males.

Relevant Physiology and Pathophysiology

The major risk factors for the development of testis cancer are male gender and cryptorchidism. However, maldescent of the testis does not seem to be causal in the development of testicular cancer but rather a marker for some genetic or dysgenic event in embryonic or fetal life. The opposite normally descended testis develops cancer in about one quarter of cryptorchid testis cancer patients. Orchiopexy fails to restore normal cancer risk to the patient with testicular maldescent, but it does allow adequate examination of the testis for development of cancer. Other risk factors include various genitourinary abnormalities such as inguinal hernia, ureteral duplication, abnormal lobulation or orientation of the kidney, and testicular hydroceles.

Germ cell tumors of the testis represent greater than 90% of all tumors of the testis. These tumors appear to arise from a pluripotent germ cell capable of differentiating into embryonic structures (teratoma and embryonal carcinoma), placental structures (yolk-sac tumor and choriocarcinoma) or seminoma (the most primitive germ cell tumor). Germ cell cancers may express features of only one of these histopathologies or mixtures of two or more. Other malignancies of the testis include lymphoma (the most common non-germ cell cause of testicular malignancy in elderly men), metastatic cancer or leukemia, tumors of the testicular stroma, and other rare tumors.

Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Tests

The diagnosis of germ cell tumor of the testis requires histopathologic examination of tissue obtained from an orchiectomy specimen. Inguinal orchiectomy, rather than transcrotal biopsy, is the preferred surgical approach for retrieval of diagnostic testicular tissue. The risk of contamination of the scrotal skin followed by local recurrence of cancer or risk of distribution of microscopic metastases to inguinal lymphatic drainage is circumvented. Because the tumor may contain histologic mixtures of several germ cell elements, it is essential that a total orchiectomy specimen plus a generous margin of spermatic cord be provided the pathologist. Occasionally extragonadal germ cell tumors may present within the mediastinum or retroperitoneum without an identifiable testicular tumor. A major proportion of patients with these unusual malignancies may expect cure with systemic chemotherapy. As a consequence, representative incisional biopsy rather than wholesale excision of these frequently bulky tumors is sufficient to guide therapeutic recommendations. Ultrasonography of the testes should be performed in the event that there is doubt about which testis may harbor the tumor, that bilateral tumors are suspected, or that there is an extragonadal presentation of a germ cell tumor.

The availability of sensitive serum assays for α fetoprotein (AFP) and for the β-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) has markedly enhanced the accurate and aggressive management of patients with germ cell tumors. AFP is produced by embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac, and occasionally teratomatous components of germ cell tumors. The half-life of this glycoprotein is 5 to 7 days. β-HCG is produced by syncytiotrophoblastic cells found in seminoma, choriocarcinoma, and embryonal carcinomas.

Testicular Cancer

Relevant Physiology and Pathophysiology

Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Tests

Screening for Testicular Cancer

Differential Diagnosis

Management

Testicular cancer risks and causes

The Leather Tanners

- KEY POINTS

Environment, genetics, and testicular cancer

Established risk factors

Testicular Cancer Rates

The half-life of this glycoprotein is 18 to 24 hours. Elevation of either one or both markers before orchiectomy provides some insight into the possible representative germ cell elements in the tumor. If these markers are detectable before orchiectomy, they may be used to assess adequacy of resection. If AFP and β-HCG fail to normalize postoperatively consistent with their serum half-lives, one may be concerned about the presence of residual disease. During follow-up of patients who have undergone orchiectomy with curative intent, reappearance of the markers in serum suggests recurrent disease. Indeed, in the absence of objective evidence of recurrent cancer, marker elevation alone represents sufficient evidence of recurrent disease to warrant the intitiation of salvage treatment. Elevated tumor markers in the patient with disseminated germ cell cancer serve as an additional tool for the assessment of response to treatment. Several cautions must be kept in mind when using these markers for assistance in treatment decisions. β-HCG may be falsely elevated in patients who smoke marijuana. High levels of LH induced by hypogonadal states may produce cross-reactions with reagents used in the assay for β-HCG, producing spuriously high results. AFP can be elevated by non-germ cell malignancies (hepatocellular carcinoma and other gastrointestinal malignancies), by benign conditions (hepatitis, cirrhosis), and by mature teratoma following treatment of germ cell cancers.

Formal diagnostic evaluation for metastatic dissemination of germ cell tumors of the testis may await the confirmation of diagnosis by orchiectomy. Germ cell tumors of the testis spread in characteristic sequence to pelvic lymphatics, retroperitoneal lymphatics, and mediastinal lymphatics. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, chest x-ray and CT (or MRI) of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest should be performed. Until recently, bipedal lymphangiography has been a commonly used diagnostic study in patients with an established diagnosis of germ cell cancer. Both CT and lymphangiography provide only fair sensitivity in the detection of nodal metastases. Nevertheless, CT is the most commonly and conveniently used staging and follow-up method for the majority of patients. In patients with disseminated cancer, lung metastases are commonly observed. Metastases are less frequently observed in liver, brain, and other solid organs and viscera, usually representing late manifestations in patients with prolonged survival or delayed recurrence after systemic therapy. Consequently, other radiologic studies (e.g., bone scans, CT of the brain, gallium studies) should be reserved for patients with symptoms suggesting that disease is likely to be detected by these means.

Differential Diagnosis

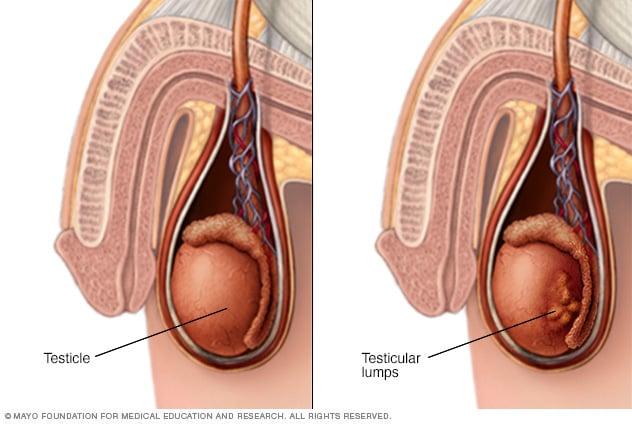

The cardinal diagnostic finding in the patient with testis cancer is a mass in the substance of the testis. Unilateral enlargement of the testis with or without pain in the adolescent or young adult male should raise concern for testis cancer. The differential diagnosis includes hydrocoele, spermatocoele, epididymitis, testicular torsion, or infectious orchitis. Epididymitis, orchitis, and testicular torsion tend to be acutely painful conditions, unlike testis cancer, which produces sensations of heaviness or aching. The inflamed epididymis can usually be differentiated from testis cancer by physical examination. Transillumination or ultrasonography of the testis differentiates the solid mass of testis cancer from the fluid densities of spermatocoele and hydrocoele. Metastatic testis cancer is often associated with back, flank, or chest pain from massively enlarged lymph nodes. Extragonadal germ cell tumors are a common cause of superior vena cava syndrome. These tumors may also produce chest pain, dyspnea, or difficulty swallowing. Extragonadal germ cell cancers are often identified by elevated serum tumor markers in a patient with a mediastinal or abdominal mass and biopsy evidence of poorly differentiated cancer.

Management

The management of established testis cancer is closely allied with its clinical stage. The inguinal orchiectomy is a therapeutic operation, in addition to its importance as a diagnostic procedure. Whether additional interventions are required in the patient with newly diagnosed testis cancer depends on evidence of more advanced cancer yielded by ancillary diagnostic studies and the known risk of recurrence for each stage of cancer at presentation. A variety of staging systems of testis cancer are used in clinical practice. For the purpose of this discussion, the Memorial Sloan-Kettering staging system will be used (Table 97-4).

For patients with clinical stage A nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (confined to the testis), inguinal orchiectomy may be sufficient therapy for selected individuals. It must be realized that patients with clinical stage A disease with no evidence of metastatic disease by noninvasive evaluation (negative CT scans and normal serum markers) sustain a 30% risk of relapse. Since most first recurrences of testis cancer involve the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) lends substantial accuracy to the detection of microscopic lymph node disease at the time of cancer presentation. Some controversy remains regarding the necessity for RPLND in all patients, since (1) the procedure harbors some risk for surgical morbidity (retrograde ejaculation) and (2) salvage chemotherapy is sufficiently effective that cure may be anticipated in the vast majority of patients with recurrent cancer. A reasoned approach might involve the application of RPLND for patients with clinical stage A cancer for whom follow-up reliability is in question, for whom the prospect of a 30% recurrence rate is intolerable, or for whom histopathologic prognostic factors (presence of embryonal carcinoma or yolk sac elements, lymphatic or vascular invasion, or extension of tumor beyond the testis) suggest adverse outcome. Expectant follow-up after orchiectomy may be entirely warranted for individuals who are likely to adhere to intensive follow-up and for whom avoidance of the risk of surgical morbidity is desired.

For patients with stage B disease (involvement of retroperitoneal lymph nodes) discovered at RPLND (pathologic stage B1 or B2), the risk of later relapse is a nearly intolerable 50%. Such patients are usually offered two to four courses of cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by an expectation for cure in the vast majority. Patients with radiologic evidence of retroperitoneal lymph node involvement (clinical stage B2) are most often treated with chemotherapy. RPLND is not performed for clinical stage B2 patients in whom resection of a residual mass will be required following chemotherapy. This approach achieves long-term survival in more than 90% of patients with stage B1-2 nonseminomatous testicular cancer. Patients with bulky (stage B3) cancer are rarely candidates for primary surgery. Multiagent cisplatin-based chemotherapy is routinely used in this setting with the goal to achieve complete radiologic and serologic (tumor marker) remission. RPLND is then undertaken for any residual tumor mass. In the event that tumor markers remain elevated or that the tumor does not respond to systemic treatment, salvage chemotherapy may be implemented (see later discussion).

The treatment of patients with pure seminoma of the testis relies heavily on primary or adjunctive radiotherapy following diagnostic biopsy. For greater than 90% of patients with clinical stages A to B2 seminoma, irradiation of the infradiaphragmatic lymph nodes at relatively low doses (2500 cGy) accomplishes remission and long-term survival. For patients with bulky abdominal disease (clinical stage B3), chemotherapy is favored and produces remission and cure in approximately 90% of such individuals.

For the patient who comes to medical attention with advanced (clinical stage C) disease in supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes, viscera, solid organs, soft tissues, and/or bone (a rare event in patients with seminoma), chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. The chemotherapeutic management of patients with testicular cancer represents one of the most important advances in cancer treatment, contributing to reliably curative multidisciplinary therapy for approximately 96% of testis cancer patients diagnosed annually. A chemotherapy regimen developed at Indiana University utilizing cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin (PEB) has received wide acceptance as a safely administered and highly effective means to treat advanced or recurrent cancer (Table 97-5). Three to four courses of this regimen are curative for greater than 90% of patients with "good-risk" disseminated nonseminomatous germ cell cancer or pure seminoma. For patients manifesting "poor-risk" characteristics such as large-volume, bulky cancer, nonlung visceral organ involvement, and high levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), AFP, and β-HCG, initial management may include PEB chemotherapy or participation in ongoing clinical trials. Thirty-five to forty percent of patients with poor-risk disseminated cancer relapse after such therapy. Additional methods for improving the disease management and survival of relapsing patients include the liberal use of surgery to resect residual tumor masses, salvage chemotherapy, and, rarely, high-dose chemotherapy with or without autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell rescue.