Health Centers > Cancer Health Center > Carcinoma of the Urethra

Carcinoma of the Urethra

Carcinoma of the Urethra Introduction

Female Urethral Carcinoma

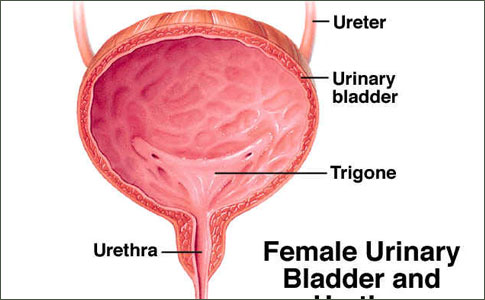

The female urethra is largely contained within the anterior vaginal wall. In the adult it is 2 to 4 cm in length. Distally, it is lined with stratified squamous epithelium, changing to stratified or pseudostratified columnar epithelium more proximally. At the bladder neck, the mucosa is transitional cell epithelium.

The histopathology of female urethral cancer depends upon the tissue of origin. Squamous carcinoma is the most common, comprising about 50% of all tumors. Transitional cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are next most common and occur with roughly equal frequency. Unlike penile cancers, tumor grade does not appear to influence either propensity for metastasis or prognosis. Female urethral cancers occur more often in white women than in black women. Mixed tumors, undifferentiated carcinomas, melanoma, cloacogenic carcinoma, and clear cell adenocarcinoma have also been reported.

Urethral cancers spread first by local extension and later metastasize via lymphatic channels and bloodborne routes. The lymphatic drainage of the distal urethra and labia is to the superficial and deep inguinal nodes. The proximal urethra drains to the nodes of the iliac, obturator, presacral, and para-aortic lymphatic chains. Palpably abnormal lymph nodes are present in 20% to 50% of patients at presentation, and almost always represent metastatic cancer. Metastases to distant sites - liver, lung, brain and bone - occur late and are more common with adenocarcinomas.

Staging Table 112-3 shows the AJCC/UICC (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer) TNM staging system for urethral carcinoma. One system is now used for both male and female patients. Older literature commonly refers to tumors involving the distal third of the urethra as "anterior" or "distal" lesions, while those involving the proximal two thirds are described as "posterior" or "proximal" tumors. These designations are useful in predicting the clinical behavior of urethral cancers and are still often used. Roughly half of tumors involve the entire length of urethra at diagnosis.

A rare variation of urethral cancer is carcinoma arising in a urethral diverticulum. These tumors are usually squamous carcinomas and are usually located in the distal two thirds of the urethra. They have been reported more frequently in black women than in white women, and likely arise from remnants of wolffian or mullerian ducts or ectopic cloacal epithelium.

Surgical Management In the female, most tumors present with bleeding or distal urethral mass. Distal urethral or anterior lesions usually present early and are diagnosed while at low stage. These tumors have been successfully managed with local excision, transurethral resection, partial urethrectomy, and fulguration or ablation with either neodymium:YAG or CO2 laser techniques. In rare instances, higher stage local lesions may be managed with total urethrectomy and preservation of the bladder with interposition of a catheterizable segment or with the Mitrofanoff procedure.

More proximal lesions present later and at higher stage than distal lesions. Progressive obstructive symptoms are the hallmark of proximal or "posterior" urethral lesions. For superficial tumors, transurethral resection or laser surgery may be appropriate. Advanced or extensive lesions, and those which involve the bladder or vagina, may necessitate cystectomy or anterior exenteration with urinary diversion. Local recurrence in such high-stage disease occurs frequently.

In advanced disease, metastases to the lymph nodes are present in 50% of cases. Inguinal node dissection should be performed in the presence of palpably enlarged nodes, and pelvic node dissection should be performed when proximal involvement of the urethra is identified. There does not appear to be any therapeutic advantage to prophylactic node dissection when the inguinal nodes are not enlarged.

Tumors of the Penis and Urethra

Cancer of the penis is a rare disease in the United States and Europe, but is a major health problem in parts of South America, Africa, and Asia. Incidence of squamous carcinoma of the penis, by far the most common penile cancer, ranges from 0.4% of male genital cancers in the United States, to as high as 20% to 22% in China and Uganda. Other cancers involving the penis are epidemic Kaposi sarcoma, verrucous carcinoma, and transitional cell carcinoma.

Urethral cancer is quite rare, with some 600 reported cases in males and some 1,600 cases in females. It is the only genitourinary malignancy which occurs more frequently in women than in men. Squamous cell carcinoma predominates in both males and females, with transitional cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma encountered less commonly.

Radiation Therapy - Radiation therapy, administered as both external beam radiation and brachytherapy, has been used for definitive treatment of both localized and advanced tumors. It has also been used to downsize tumors before definitive surgical intervention. Results have been mixed, with 5-year survivals averaging approximately 35% in advanced disease. Side effects and complications, including edema, fistulae, and damage to the bowel, are commonplace.

Chemotherapy and Combined Therapy - The rarity of these tumors has precluded much meaningful clinical research in chemotherapeutic treatment, or in chemotherapy combined with radiation or surgery. Combination chemotherapy in conjunction with radiation and surgery has produced promising outcomes in squamous carcinomas of the head and neck, anus, and penis, and may be expected to demonstrate similar benefit in squamous cancers of the urethra. However, multinational, multiinstitutional trials are required to provide clinical data to assess the efficacy of any such treatment regimens.

Prognosis - Long-term survival is related to the stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis and appears to be independent of tumor histology or grade. Bracken and associates, in one of the few large series, report an overall 5-year survival of 32% in 81 patients. Patients whose tumors were less than 2 cm in diameter did significantly better than those with tumors larger than 5 cm in diameter. Patients with tumors of the anterior or distal urethra had better survival than those with more proximal lesions, apparently because their tumors presented earlier in their clinical course. Patients with tumors involving the entire urethra fare the worst, with a 5-year survival of only 11%. Tumor recurrence rates of 66% to 100% have been noted

Male Urethral Carcinoma

The male urethra averages some 18 cm in length, and is subdivided into the penile urethra, the membranous urethra, and the prostatic urethra. Beginning distally, the penile urethra is comprised of the meatus and fossa navicularis which is lined with stratified squamous epithelium. The pendulous urethra extends from the proximal fossa navicularis to the suspensory ligament of the penis, where it then becomes the bulbar urethra between the ligament and the urogenital membrane. These areas are lined with stratified or pseudostratified columnar epithelium as is the short (1.5 cm) membranous urethra. This contains the external sphincter which is comprised of striated muscle fibers. The prostatic urethra passes through the prostate and is lined with transitional cell epithelium.

Fifty percent to 75% of male urethral cancers arise in the bulbar urethra. The remainder occur predominantly in the fossa navicularis. Approximately 90% of male tumors demonstrate squamous cell carcinoma histology. Often there is an association with stricture of the urethra (Figure 112-7). Infrequently, transitional cell carcinoma or undifferentiated tumor may predominate at the bladder neck or within the prostatic urethra. Poorly differentiated transitional cell cancers may show some squamous characteristics. Rarely adenocarcinoma may arise in the glands of Littre or the prostatic utricle. Metastases from distant tumor sites to the penis also occur infrequently.

Obstructive symptoms are common in more proximal lesions, while urethral bleeding and palpation of a mass herald more distal lesions (Figure 112-8). In general, the more proximal a tumor, the later in its development and the higher its stage at diagnosis.

A special case exists in the urethral segment which is retained following cystectomy. These tumors are almost exclusively transitional cell carcinomas. Monitoring of the urethra in this situation and management of these tumors is discussed elsewhere. When the urethra is excised, either in conjunction with cystectomy or as a secondary procedure, the entire urethra, including the fossa navicularis, must be excised.

Lymphatic drainage of the distal male urethra is similar to that of penile tumors. Tumors of the fossa and pendulous urethra drain to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, while tumors of the bulbar, membranous, and prostatic urethral segments drain to the iliac, obturator, and presacral node groups. There may be crossover at the prepubic lymphatic plexus.

Staging Table 112-3 shows the AJCC/UICC Staging System for urethral carcinoma. Special provision is now made for the staging of transitional cell carcinoma of the prostatic urethra and ducts. The terminology of distal or "anterior" tumors - those distal to the suspensory ligament - and proximal or "posterior" tumors - those involving the bulbar, membranous, and prostatic segments - may be encountered.

Surgical Management Low-grade, low-stage tumors of the urethra may lend themselves to transurethral resection or laser fulguration, but such lesions are rare. Excisional biopsy may be feasible, and biopsy prior to laser fulguration is essential to assess histopathology and tumor depth.

Selected lesions of the distal urethra may lend themselves to partial penectomy. Tumors must not involve the corpus spongiosum or the corpora cavernosa, and must be amenable to a 2-cm margin. More advanced or more proximal lesions may require a total penectomy with creation of a perineal urethrostomy. Proximal cancers may necessitate an anterior exenteration with radical cystoprostatourethrectomy and urinary diversion.

Inguinal and pelvic lymphadenopathy portends metastatic disease. Careful serial palpation of the groins as well as interval pelvic CT evaluations are essential in the follow-up of definitive treatment of a urethral primary. Inguinal node dissection should be performed in the presence of clinically positive groin nodes. This has been curative in many cases. In several small series, 5-year survival following inguinal node dissection ranged from 12% to 66%. Pelvic node dissection has also proven curative in an occasional case and is worthwhile, although the prognosis in pelvic nodal disease is much worse than with inguinal node involvement. In the absence of inguinal adenopathy, inguinal lymphadenectomy is probably not warranted.

Radiation, Chemotherapy, and Combined Therapy Experience with these modalities is limited, although some success in treating superficial, low-grade lesions with external-beam radiotherapy in both males and females has been achieved. Brachytherapy implants and molds have also been used.

The infrequency with which these tumors are encountered has made it impossible to amass much experience with chemotherapy, but it might be anticipated that combination chemotherapy with drugs similar to those used in squamous carcinoma of other sites or with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and penis may be similarly effective in urethral lesions of similar pathology. Again, the use of these treatment modalities as well as the employment of combined therapy programs requires large, international, multiinstitutional studies to acquire data sufficient for meaningful interpretation.

Summary

Cancers of both the male and the female urethra are quite rare, but the disease may be devastating if not recognized and treated as early as possible. Early surgical or radiotherapeutic intervention may cure these tumors. Advanced disease, at least for the present, tends to carry a grim prognosis. Effective programs of surgery or radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy have not been developed, although such programs - based on experience with tumors of similar histopathology in other systems - have the potential for improving outcome. With improvements in treatment and with increased availability of modern diagnostic techniques, combination chemotherapy, worldwide communications and data transmission, there is hope that multinational, multiinstitutional programs of treatment may provide effective therapy for those suffering from these cancers while expanding our effectiveness in managing them.

References

1. Lynch DF, Schellhammer PF. Tumors of the penis. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998;2453-86.

2. Puras A, Gonzales-Flores B, Rodriguez R. Treatment of carcinoma of the penis. Proc Kimbrough Urol Semin 1978;12:143-149.

3. Schmauz R, Jain DF. Geographical variation of carcinoma of the penis in Uganda. Br J Urol 1971;25:25-29.

4. Gilliland F, Key CR. Male genital cancer. Cancer 1995;75:295-315.

5. Martinez I. Relationship of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix uteri to squamous cell carcinoma of the penis among Puerto Rican women married to men with penile cancer. Cancer 1969;24:777-780.

6. McCance DJ, Kalache A, Ashdown K. HPV type 16 and 18 in carcinoma of the penis from Brazil. Int J Cancer 1986;37:55-59.

6a. Moore TO, Moore AY, Carrasco D, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and cancer. J Cutaneous Med Surg 2001;5:323-28.

6b. Tsen HF, Morgenstern H, Mack T, et al. Risk factors for penile cancer: results of a population-based case-control study in Los Angeles County (United States). Cancer Causes and Control 2001;12:267-77.

7. Schwartz RA. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Skin cancer - recognition and management. New York: Springer- Verlag; 1988:25-35.

8. Fraley EE, Zhang G, Manivel C, Niehans GA. The role of ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy and significance of histological differentiation in treatment of carcinoma of the penis. J Urol 1989;142:1478-82.

9. McDougal WS, Kirchner FK Jr, Edwards RH, Killion LT. Treatment of carcinoma of the penis: the case of primary lymphadenectomy. J Urol 1986;136:38-41.

10. Theodorescu D, Russo P, Zhang ZF. Outcomes of initial surveillance of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis and negative nodes. J Urol 1996;155:1626-31.

11. Sherman RN, Fung HK, Flynn KJ. Verrucous carcinoma (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor). Int J Dermatol 1991;30: 730-31.

12. Boshart M, zur Hausen H. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in Buschke-Lowenstein tumors: physical state of the DNA and identification of a tandem duplication in the non-coding region of a HPV-6 subtype. J Virol 1986;58:963.

13. Fowler JE. Sentinel node biopsy for staging of penile cancer. Urology 1984;23:352-53.

14. Greene FL, Balch CM, Page DL, et al, ediotrs. Penis. In: American Joint Committee onCancer (AJCC) CAncer Staging Manual. 6th edition. New York:Springer-Verlag;2002:303-308.

15. Ekstrom T, Edsmyr F. Cancer of the penis: a clinical study of 229 cases. Acta Chir Scand 1958;115:25-45.

16. Hanash KA, Furlow WL, Utz DC, Harrison EG Jr. Carcinoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study. J Urol 1970;104:291-7.

17. Mohs FE, Snow SN, Messing EM, Kuglitsch MG. Microscopically controlled surgery in the treatment of carcinoma of the penis. J Urol 1985;133:961-6.

18. Blastein LM, Finklestein LH. Laser surgery for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1990;90:338-42.

19. de Kernion JB, Tynbery P, Persky L, Fegen JP. Carcinoma of the penis. Cancer 1973;32:1256-62.

20. Puras-Baez A, Rivera-Herrera J, Miranda G, et al. Role of superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy in carcinoma of the penis. J Urol 1995;153:246A.

21. Catalona WJ. Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with preservation of saphenous veins: technique and preliminary results. J Urol 1988;140:306-10.

22. Hardner GJ, Bhanalaph T, Murphy GP, et al. Carcinoma of the penis: analysis of therapy in 100 consecutive cases. J Urol 1972;108:428-30.

23. Kossow JH, Hotchkiss RS, Morales PA. Carcinoma of the penis treated surgically: Analysis of 100 cases. Urology 1973;2:169-72.

24. Ornellas AA, Correia AL, Marota A, Seixas ALC. Surgical treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: Retrospective analysis of 350 cases. J Urol 1994;151:1244-47.

25. Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer 1977;39:456-66.

26. Perinetti EP, Crane DB, Catalona WJ. Unreliability of sentinel node biopsy for staging penile cancer. J Urol 1980;124:734-35.

27. Srinivas V, Morse MJ, Herr HW, et al. Penile cancer: relation of extent of nodal metastasis to survival. J Urol 1987;137:880-82.

28. Lynch DF. Commentary on: Srinivas SV. Relation of extent of nodal metastasis to survival. Semin Urol Oncol 15;1997:136-9.

29. Gerbaulet A, Lambin P. Radiation therapy of cancer of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 1992;19:325-32.

30. Pointon RCS, Poole-Wilson DS. Primary Carcinoma of the urethra. Br J Urol 1968;40:682-93.

31. Kelley CD, Arthur K, Rogolf F, Grabstald H. Radiation therapy of penile cancer. Urology 1974;4:57-73.

32. Delannes M, Malavaud B, Douchez J, et al. Iridium192 interstitial therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992;24:479-83.

33. Edsmyr F, Andersson L, Pier-Luigi E. Combined bleomycin and radiation therapy in carcinoma of the penis. Cancer 1985;56:1257-63.

34. Lebourgeois JP, Frikha H, Piedbos P, LePechoux C. Radiotherapy in the management of epidemic Kaposi's sarcoma of the oral cavity, eyelid, and the genitalia. Radiother Oncol 1994;30:263-66.

35. Ravi R. Correlation between the extent of nodal involvement and survival following groin dissection for carcinoma of the penis. Br J Urol 1993;72:817-19.

36. Horenblas S, Van Tinteren H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis IV: prognostic factors of survival, analysis of tumor, nodes, and metastasis classification system. J Urol 1994;147:153-58.

37. Pizzocaro G, Piva L, Bandieramonte G, Tana S. Up-to-date management of carcinoma of the penis. Eur Urol 1997;32:5-15.

38. Dexeus FH, Logothetis CJ, Sella A, et al. Combination chemotherapy with methotrexate, bleomycin, and cisplatin for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the male genital tract. J Urol 1991;146:1284-87.

39. Haas GP, Blumenstein BA, Gaggiano RG, et al. Cisplatin, methotrexate, and bleomycin for the treatment of carcinoma of the penis: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Urol 1999;161:1823-25.

40. Mostofi FK, Davis CJ Jr, Sesterhenn IA. Carcinoma of the male and female urethra. Urol Clin North Am 1992;19:347-58.

41. Bracken RB, Johnson DE, Miller LS, et al. Primary carcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol 1976;116:188-92.

42. Chu AM. Female urethral carcinoma. Radiology 1973;107:627-30.

43. Narayan P, Konety B. Surgical treatment of female urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 1992;19:373-82.

44. Greene F., Balch CM, Page DL, et al, editors. Urthra. In: American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition. New York: Springer-Verlag;2002:341-346.

45. Tines SC, Bigongiari LR, Weigel JW. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:582-84.

46. Tesluk H. Primary adenocarcinoma of the female urethra. Urology 1981;17:197-99.

47. Staeler C, Chaussy C, Jocham D, et al. The use of neodymium:YAG lasers in urology: indication, technique, and critical assessment. J Urol 1985;134: 1155-60.

48. Schaeffer AJ. Use of the CO2 laser in urology. Urol Clin North Am 1986;13:393-404.

49. Weghaupt K, Gerstner GJ, Kucera H. Radiation therapy for primary carcinoma of the female urethra: a survey of over 25 years. Gynecol Oncol 1984;17:58-64.

50. Ray B, Canto AR, Whitmore WF Jr. Experience with primary carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 1977;117: 591-94.

51. Schellhammer PF, Whitmore WF Jr. Transitional cell carcinoma of the urethra in men having cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol 1976;115:56-60.

52. Zeidman EJ, Desmond P, Thompson IM. Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. Urol Clin North Am 1992;19:359-72.

53. Hoppman HJ, Fraley EE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Urol 1978;120:393-98.

54. Marshall VF. Radical excision of locally extensive carcinoma of the deep male urethra. J Urol 1957;78;2 52-65.

55. Jackson SM: The treatment of carcinoma of the penis. Br J Surg 1966;53:33-35.