Health Centers > Diabetes Center > Diabetic Emergencies in the Dental Office

Diabetic Emergencies in the Dental Office

The most common diabetic emergency in the dental office is hypoglycemia, a potentially life-threatening complication that must be managed accordingly. Signs and symptoms include confusion, sweating, tremors, agitation, anxiety, dizziness, tingling or numbness, and tachycardia. Severe hypoglycemia may result in seizures or loss of consciousness.

Diabetes Mellitus and Oral Diseases

Diabetes Introduction

Diabetes Epidemiology and classification

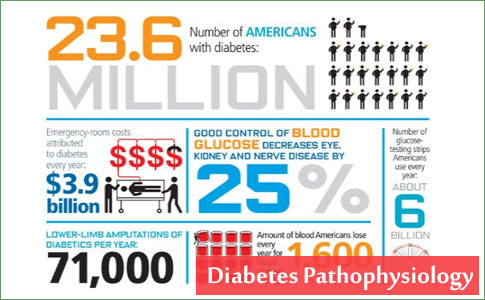

Diabetes Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation, Laboratory findings, and Diagnosis

Diabetes Complications

Diabetes Management

L Introduction

L Oral Agents

L Insulin

Oral Diseases and Diabetes

Periodontal Health and Diabetes

Dental Management of the Diabetic Patient

Conclusion

References

As soon as a patient experiences signs or symptoms of possible hypoglycemia, he or she should check the blood glucose with a glucometer. If a glucometer is unavailable, the condition should be treated presumptively as a hypoglycemic episode. The dental practitioner should give the patient approximately 15 g of oral carbohydrate in a form that will be absorbed rapidly.

If the patient is unable to take food by mouth and an intravenous line is in place, 25 to 50 mL of a 50% dextrose solution (D50) or 1 mg of glucagon can be given intravenously.

If an intravenous line is not in place, 1 mg of glucagon can be injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly at almost any body site. Glucagon injection causes rapid glycogenolysis in the liver, releasing stored glycogen and rapidly elevating blood glucose. Following treatment, the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia should resolve in 10 to 15 minutes. The patient should be observed for 30 to 60 minutes after recovery. Evaluation by glucometer can ensure that normal blood glucose levels have been achieved before the patient is released.

Blood sugar levels that are too high or too low can quickly turn into a diabetic emergency without quick and appropriate treatment. The best way to avoid dangerously high or low blood glucose levels is to self-test to stay in tune with your body and to stay attuned to the symptoms and risk factors for hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome.

Low Blood Sugar Emergencies (Hypoglycemia)

Hypoglycemia is sometimes called insulin reaction because it is more frequent in people with diabetes who take insulin. However, it can occur in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and is also commonly caused by certain oral medications, missed meals, and exercise without proper precautions. The typical threshold for hypoglycemia is 70 mg/dl (3.9 mmol/l), although it may be higher or lower depending on a patient's individual blood glucose target range. Symptoms include erratic heartbeat, sweating, dizziness, confusion, unexplained fatigue, shakiness, hunger, and potential loss of consciousness. Once a low is recognized, it should be treated immediately with a fast-acting carbohydrate such as glucose tablets or juice.

High Blood Sugar Emergencies (DKA or HHNS)

Extremely high blood glucose levels can lead to one of two conditions diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome (HHNS; also called hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma). Although both syndromes can occur in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, DKA is more common in type 1 and HHNS is more common in type 2.

The Hypoglycemic States

Spontaneous hypoglycemia in adults is of two principal types: fasting and postprandial. Symptoms begin ...

In some instances, marked hyperglycemia may present with symptoms mimicking hypoglycemia. If a glucometer is not available, these symptoms must be treated as hypoglycemia. If the event was actually hyperglycemia, the small amount of extra glucose derived from treatment will generally not have a significant effect.

On the other hand, if glucose-elevating emergency treatment was withheld from a patient in a mistaken belief that the emergency was related to elevated glucose levels when hypoglycemia was in fact present, severe adverse outcomes are possible. The best means of determining the true nature of a glucose-related emergency is to check the blood glucose level with a glucometer.

Because hyperglycemic emergencies develop more slowly than does hypoglycemia, they are less likely to be encountered in the dental office. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar nonketotic acidosis require immediate medical evaluation and treatment. In the dental office, care is limited to activating the emergency medical system, opening the airway and administering oxygen, evaluating and supporting circulation, and monitoring vital signs. The patient should be transported to a hospital as soon as possible.

Patients with severe hyperglycemia should immediately undergo assessment and stabilization of their airway and hemodynamic status. Naloxone, to reverse potential opiate overdose, should be considered for all patients with altered mentation. Thiamine, for acute treatment of Wernicke's encephalopathy, should be considered in all patients with signs of malnutrition. In cases requiring intubation, the paralytic succinylcholine should not be used if hyperkalemia is suspected; it may acutely further elevate potassium.

Immediate assessment also includes placing patients on a cardiac monitor and oxygen as well as obtaining vital signs, a fingerstick glucose, intravenous (IV) access, and an electrocardiogram to evaluate for arrhythmias and signs of hyper- and hypokalemia.

The differential diagnosis for hyperglycemic crisis includes the "Five I's": infection, infarction, infant (pregnancy), indiscretion (including cocaine ingestion), and insulin lack (nonadherence or inappropriate dosing). In addition to clinical history and physical examination, diagnostic tests should include a venous blood gas,complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and urinalysis; a urine pregnancy test must be sent for all women with childbearing potential.

Critically ill patients should undergo additional testing as clinically indicated, including a complete metabolic panel, serum osmolality, phosphate, lactate, and cardiac markers for older patients. A urine drug screen, blood alcohol level, and aspirin and acetaminophen levels should be sent for any patient with unexplained DKA and all patients with HHS. Evaluation for infection or injury should be guided by history and the physical examination. Effective serum osmolality should be calculated. The corrected serum sodium is estimated by decreasing measured serum sodium by 1.6 mEq/L for every 100 mg/dl increase in blood glucose over a baseline of 100 mg/dl; for every 100 mg/dl increment increase in blood glucose >: 400 mg/dl, measured serum sodium is decreased by an additional 4 mEq/L.

Intravenous Fluid

Critically ill patients with severe hyperglycemia resulting from DKA or HHS should be treated immediately with a bolus of normal saline. The average fluid deficit for patients with DKA is 3-5 liters; fluid resuscitation in young, otherwise healthy patients should begin with a rapid bolus of 1 liter of normal saline followed by an infusion of normal saline at 500 ml/hour for several hours.

Patients with HHS are often severely dehydrated, with cumulative fluid deficits of 10 liters or more. However, because they tend to be older and sicker, they require careful resuscitation. Expert opinion advocates for a rapid bolus of 250 ml of normal saline repeated as needed until the patient is well perfused. Fluid therapy is then continued at a rate of 150-250 ml/hour based on cardiopulmonary status and serum osmolality.

The choice and rate of IV fluid for patients with DKA who are not critically ill should be based on their corrected serum sodium and overall fluid status. While awaiting laboratory study results, most of these patients may be given a bolus of 500 ml of normal saline. Patients with mild to moderate DKA should be given normal saline at 250 ml/hour; those with an elevated corrected serum sodium should be given half-normal saline at 250 ml/hour.

Insulin therapy

Critically ill patients with DKA should be given a loading dose of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight to a maximum of 10 units followed by an infusion of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight/hour, to a maximum of 10 units/hour. Other doses and routes of insulin administration have been studied, but these have not been evaluated outside of the research setting or in critically ill patients.

Less seriously ill patients with DKA should be given an infusion of regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight/hour without a loading dose to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia. Insulin should not be started until hypovolemia has been addressed and serum potassium has been confirmed to be > 3.5 mEq/L. Giving insulin to patients with a serum potassium level < 3.5 mEq/L may precipitate life-threatening arrhythmias.

Expert opinion regarding the use of insulin for patients with HHS is mixed. Because some patients with HHS achieve euglycemia with fluid resuscitation alone,30 and given the theoretical risks of precipitating oliguric renal failure or cerebral edema in inadequately fluid-resuscitated patients, insulin should not be given as part of initial therapy. However, if the patient's serum glucose does not decrease by 50-70 mg/dl per hour despite appropriate fluid management, a bolus of IV regular insulin at 0.1 units/kg body weight to a maximum of 10 units may be given.

Electrolyte replacement

Patients with DKA or HHS experience rapid shifts in potassium during resuscitation that may trigger life-threatening arrhythmias. Death during initial resuscitation of patients with DKA is usually caused by hyperkalemia, whereas hypokalemia is the most common cause of death after treatment has been initiated. Therefore, serum potassium should be checked every 2 hours until it has stabilized in all patients with hyperglycemic crisis, and these patients should remain on a cardiac monitor. Guidelines for the treatment of hyperkalemia and hypokalemia in patients with hyperglycemic crisis based on expert opinion and our clinical experience are found in Table 2.

Many critically ill patients with DKA manifest hypophosphatemia during resuscitation. To avoid potential cardiac and skeletal muscle weakness and respiratory depression from hypophosphatemia, a serum phosphate of < 1.5 mg/dl should be repleted with K2PO4 at 0.5 ml/hour. No studies have evaluated replacement of phosphate in HHS, but critically ill patients with HHS should have their phosphate monitored and replaced appropriately.

Bicarbonate should not be used routinely in the treatment of DKA or HSS. Expert opinion suggests that it may be used in patients with DKA and severe acidosis (pH < 6.9) or in patients with severe hyperglycemia who present with a wide-complex or disorganized cardiac rhythm thought to be caused by hyperkalemia. Several small studies have shown no improvement in mortality when bicarbonate is used in patients with a pH > 6.9. Additionally, bicarbonate may prolong hypokalemia, has been associated with longer hospitalizations, and is thought to cause paradoxical acidosis of the cerebral spinal fluid and decrease oxygen tissue delivery. In children, its use has been associated with increased risk of cerebral edema.

Conclusion

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic condition affecting multiple organ systems. The oral cavity frequently undergoes changes that are related to the diabetic condition, and oral infections may adversely affect metabolic control of the diabetic state. The mechanisms underlie the oral effects of diabetes share many similarities with the mechanisms that are responsible for the classic diabetic complications. The intimate relationship between oral health and systemic health in individuals with diabetes suggests a need for increased interaction between the dental and medical professionals who are charged with the management of these patients. Oral health assessment and treatment should become as common as the eye, foot, and kidney evaluations that are routinely performed as part of preventive medical therapies. Dental professionals with a thorough understanding of current medical treatment regimens and the implications of diabetes on dental care are able to help their diabetic patients achieve and maintain the best possible oral health.