Genetic risk for type 1 diabetes driven by faulty cell recycling

Researchers, tackling a modern challenge of diabetes research, have identified a gene believed to disrupt the ability of beta cells to produce insulin resulting in type 1 diabetes.

The loss of beta cell function may be driven by a defect in Clec16a, a gene responsible for getting rid of old mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells, and making room for fresh ones. Healthy mitochondria are crucial to allowing beta cells to produce insulin and control blood sugar levels.

Little has been known about the ways in which many diabetes genes work, but a study published in the journal Cell sheds light on a genetic risk component of type 1 diabetes and a new approach for keeping beta cells strong.

“Preserving beta cells is the top priority in diabetes care,” says lead author Scott Soleimanpour, M.D., investigator at the University of Michigan’s Brehm Diabetes Research Center. “This new pathway will allow us to focus therapies on preserving healthy mitochondria within the beta cell to treat or prevent both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.”

Soleimanpour, an endocrinologist who treats patients at the University of Michigan Health System, has lived with type 1 diabetes for 30 years.

He’s made a career of studying diabetes, including a fellowship at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania where his laboratory work to understand Clec16a began.

Type 1 diabetes is the unpreventable form of diabetes that usually strikes children and young adults. It’s less common than type 2 diabetes which is associated with older age and obesity. more

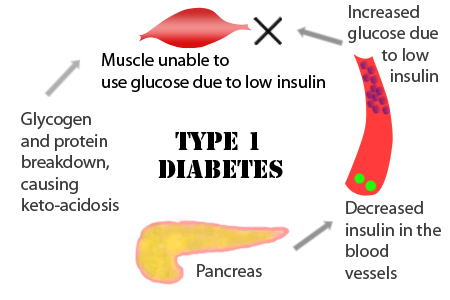

Diabetes is diagnosed when the body has an abnormally high level of glucose, or blood sugar. It’s believed that in type 1 diabetes, the body’s immune system destroys the pancreatic beta cells responsible for making insulin, a hormone the body needs to convert food into energy.

Diabetes is diagnosed when the body has an abnormally high level of glucose, or blood sugar. It’s believed that in type 1 diabetes, the body’s immune system destroys the pancreatic beta cells responsible for making insulin, a hormone the body needs to convert food into energy.

But that model may be changing after studying Clec16a mutations in both animal and human beta cells.

“Scientists are starting to appreciate the importance of beta cells in understanding why type 1 diabetes occurs,” says Soleimanpour, a U-M assistant professor of medicine. “Rather than innocent bystanders to a malfunctioning immune system, our research shows beta cells are central players in the disease itself.”

The U-M provides remarkable strength in diabetes research. Its major diabetes research program is housed at the Brehm Center for Diabetes Research – a partner of the U-M Comprehensive Diabetes Center – and brings together faculty who are experts in all complications of diabetes.

###

Additional Authors: Doris Stoffers, M.D., Ph.D., professor of medicine at UP, senior author, and colleagues from Penn School of Veterinary Medicine and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, Lund University and Skåne University Hospital in Sweden.

Funding: The research was supported by the Margaret Q. Landenberger Foundation, the Charles H. Humpton, Jr. Endowment, the JDRF (Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K08-DK089117, 5-P01-DK049210-15, 1DP3DK085708-01).

###

Shantell Kirkendoll

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

734-764-2220

University of Michigan Health System