Mild depression tied to diabetes complications

Even mild bouts of depression may worsen the health complications that often go along with type 2 diabetes, according to a new study.

Canadian researchers followed more than 1,000 patients for five years and found those who experienced multiple episodes of low-level depression were nearly three times more likely than those without depression to have greater disability, such as reduced mobility, poor self care and worse quality of life.

“Minor depression is a form of chronic stress,” said Dr. Norbert Schmitz, associate professor of psychiatry at McGill University’s Douglas Mental Health University Institute in Montreal, who led the study.

“Patients may not be able to follow treatment guidelines or they may have problems with diet, which in turn results in an increased risk of poor functioning,” he said.

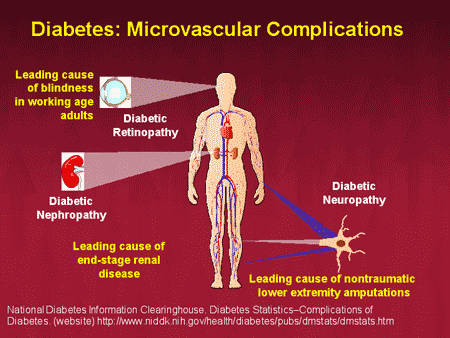

Diabetes can increase the risk of heart disease, nerve damage, kidney failure and blindness. The disease affects 25.8 million people in the U.S. and that number is expected to rise dramatically during the next 20 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Type 2 diabetes is often associated with obesity, but the elderly are also at high risk, with an estimated 27 percent of the over-65 population suffering from the disease.

Past research has found that nearly one-fifth of type-2 diabetics in the U.S. experience major depression, which is almost twice the rate seen in the general population. Some studies also link the combination of type 2 diabetes and depression with difficulty managing blood sugar levels and other health complications as well as increased risk of death.

Past research has found that nearly one-fifth of type-2 diabetics in the U.S. experience major depression, which is almost twice the rate seen in the general population. Some studies also link the combination of type 2 diabetes and depression with difficulty managing blood sugar levels and other health complications as well as increased risk of death.

Most research to date has focused on the role of major depression in poor health outcomes for diabetes patients, but Schmitz and his colleagues wanted to know if mild depression symptoms carried the same risks.

For their study, published in Diabetes Care, the researchers followed 1,064 adults, aged 18 to 80 years old, from the larger Montreal Diabetes and Well Being Study for five years.

The participants received a battery of surveys that assessed symptoms of depression, measures of disability, quality of life, diabetes-related health complications, social background, exercise and medical and psychiatric history, particularly related to treatment for depression.

The study team defined depression by a score based on symptoms experienced over a period of two weeks. While major depression would require at least five out of nine symptoms - such as appetite changes, fatigue and suicidal thinking - persisting over that time, mild depression would constitute fewer than five symptoms experienced at least once over the previous two weeks.

The researchers also looked at health-related quality of life, based on the individuals’ own perceptions of how burdensome their health problems were, and translated into a number of “unhealthy days” the person reported over the past month.

The researchers also looked at health-related quality of life, based on the individuals’ own perceptions of how burdensome their health problems were, and translated into a number of “unhealthy days” the person reported over the past month.

They found that as the number of episodes of mild depression increased, the risk of impaired health and quality of life grew as well. For participants with one minor depression episode, the rate of poor functioning in daily activities such as work, domestic responsibilities and self-care was 50 percent higher compared to those who had no depression.

For patients with four or more bouts of mild depression, the risk of poor functioning was almost 300 percent greater and the risk of impaired health-related quality of life was nearly 250 percent greater than for those without depression.

Schmitz told Reuters Health the study points to the need for broadening patient care options.

“It is important not to separate treatment for depression from treatment for diabetes,” he said. “Depression is associated with poor diabetes management. If management of diabetes is stressful, people may not follow guidelines. We need to look at the whole picture, what are the mental problems, physical problems, and try to find an integrated treatment approach to those with symptoms of depression.”

“Research has shown that integrated treatment is more effective and better at focusing on the individual,” Schmitz added. “But this approach is a recent development and integrated treatments are not widely available.”

Dr. Roger McIntyre, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, agreed diabetes patients should get early treatment with therapy for minor depression, while doctors also take a more holistic approach towards treating diabetes, including helping patients improve their quality of life and ability to care for themselves.

“This obviously requires an intensive resource-heavy approach,” McIntyre said. “And the reality is that these resources are not available and patients need to be self managers and need to work in partnership with providers.”

###

SOURCE: Diabetes Care, online November 6, 2013