Fecal incontinence in the elderly

FI in the elderly is often multifactorial. It may be the result of structural and functional decompensation. Impairment of the anorectal unit, such as weakness from prolonged straining secondary to constipation or overt anal tears seen after vaginal delivery in women (35%), are common causes of FI. The injury sustained from obstetric trauma is often delayed in onset; many women do not manifest symptoms until their 50s.

Idiopathic FI is an entity frequently ascribed to women with idiopathic denervation of the PBR muscle and the EAS. Many of these women are multiparous and lack other predisposing factors. Other factors implicated in the cause of idiopathic FI are nerve entrapment, descending perineum syndrome, as well as central and peripheral neuropathy.

The consistency and volume of stool may be a contributing factor in the development of FI. Diarrhea and constipation exacerbate FI. Chronic diarrhea from illnesses such as inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, bacterial overgrowth, short-bowel syndrome, celiac disease, bile acid malabsorption, and diabetic diarrhea overwhelms the anorectal unit and places individuals at risk for FI.

Fecal impaction is reported to occur in more than 40% of elderly patients admitted to the hospital. Read et al found no significant difference in anal pressures and maximum basal and squeeze sphincter pressures between impacted individuals and controls. However, perianal sensation was found to be absent or impaired in 74% and 77% of impacted patients, respectively, with only 29% of patients being able to distinguish between gas and liquid in the anal canal. It is believed that impaired sensation prevents patients from guarding against the relaxation of the EAS that occurs with rectal distention, preventing the voluntary contraction of the external sphincter and PBR muscle unit. With the administration of laxatives, FI is further aggravated by the leakage of fecal material around the impacted mass, leading to paradoxical diarrhea.

Clinical evaluation

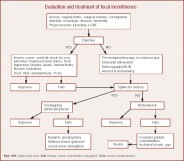

Patients with predisposing medical conditions should trigger a specific line of questions by the practitioner regarding FI (see the algorithm). Obtaining information on the frequency and nature of FI may help clinical practitioners understand the severity of incontinence and its impact on the patient’s quality of life. History taking should include onset, frequency, characterization of bowel habits, consistency of stool, awareness of the desire to defecate, and risk factors. Travel history should also be discussed as well as medication history including recent antibiotic use (see Table 2). Patients may report FI in the setting of loose, copious stool that may result from the inability of the rectum to hold large volumes of loose stool.

Table 2 - Evaluation and treatment of fecal incontinence

Table 2 - Evaluation and treatment of fecal incontinence

A multisystem physical examination should include a complete anorectal examination conducted in both the left lateral decubitus and seated positions. Digital rectal exam (DRE) allows for a subjective assessment of resting and squeeze pressures (the pressure generated by the patient when asked to contract the sphincter for ≥ 30 seconds), presence of a mass, fecal impaction, scars, a thin perineal body, anal fissures, and pain on examination. The positive predictive value of the DRE for identifying resting and squeeze pressures is 67% and 81%, respectively.

The normal anterior and upward lift of the PBR sling, perianal sensation, and elucidation of the anal wink provides good assessment of neuromuscular functioning. The anal wink is tested by stroking the skin lateral to the anal opening, which should elicit contraction of the anus in normal patients. The absence of this reflex suggests neural damage (pudendal nerves and S4 nerve roots). The discovery of fecal impaction may predispose to overflow incontinence in the elderly and points to the need for disimpaction with an enema and institution of a good bowel regimen. Scars from prior surgery and fistulas may be evident as well as hemorrhoids, and ballooning of the perineum, which may be a sign of a weak pelvic floor. Further, during the performance of the Valsalva’s maneuver, a gaping or open anus suggests rectal prolapse or a neurologic disorder.

Diagnostic testing

The use of diagnostic testing in the elderly should be governed by the patient’s comorbidities, expected life span, symptom severity, suspected etiology, and response to medical management. The primary diagnostic modalities available for the evaluation of FI include flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, anorectal manometry, endoanal ultrasound (EAUS), evacuation proctography (defecography), pelvic MRI, and electromyography of the external sphincter (see Table 3). These procedures are performed in specialized clinical laboratories under the auspices of a gastroenterologist, radiologist, colorectal surgeon, or neurologist. To ensure quality control and patient safety, the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society is currently considering the formal registration and listing of all laboratories that regularly perform these clinical tests.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy is recommended in most elderly patients with FI. Visualization of the rectosigmoid mucosa should be considered to rule out structural problems such as internal hemorrhoids, fistulas, fissures, neoplasm, or inflammation associated with ischemia, colitis, and pseudomembranes. Sigmoidoscopy can be done at the bedside in patients with limited mobility or varying degrees of dementia. Colonoscopy should be performed in patients without significant morbidities, as this procedure is invasive and requires sedation.

Anorectal manometry This allows for the assessment of IAS resting pressure, maximum squeeze pressure, the sphincter length, and the integrity of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex and rectal sensation. Measurements are taken as a rectal pressure catheter with a balloon at the tip is slowly withdrawn in 0.5- to 1-cm intervals from the rectum to the anal verge. Measurements are also taken during various simulated events such as the Valsalva’s maneuver and postponement of defecation. Anal resting and squeeze pressures are frequently observed to be reduced in FI. Normal values are influenced by age, gender, and the technique utilized, and they need to be compared against normal values obtained in age- and gender-matched subjects. The anal canal length and maximal squeeze pressures are greater in men when compared to parous women. However, this difference is not seen in the resting anal pressure of nulliparous women. Studies have shown that maximum squeeze pressures have good sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between FI and controls. Interestingly, in most cases, there is little improvement in manometric measures with successful treatment of FI. Anal manometry requires patients to be able to follow directions for accurate completion of the test, so demented patients are not good candidates.

Rectoanal sensory testing The rectal balloon sensory testing allows assessment of the awareness of rectal distention. During rectal balloon distention, thresholds for first perception, desire to defecate, and maximal tolerable volume are measured. In normal controls, the reflex is seen after instillation of 10 to 30 mL of air and induces a desire to pass flatus after 40 to 50 mL of air is instilled. Rectal compliance as measured by balloon distention assesses the patient’s ability to postpone defecation to a convenient time. Patients must be able to follow commands for the completion of this test.

Table 3 Diagnostic studies for fecal incontinence

Table 3 Diagnostic studies for fecal incontinence

Endoanal ultrasound EAUS is useful for assessing morphologic anomalies of the anal sphincters such as sphincter thinning, scars, defects, and fistulae. Three-dimensional images are obtained using a 7-MHz or 10-MHz transducer providing a 360-degree view of the anal canal. It allows accurate visualization of the IAS; however, assessment and interpretation of EAS may be more operator dependent and confounded by normal anatomic variants as well as interobserver variability. In experienced hands, the sensitivity and specificity of this method approaches 100% in identifying defects of both the EAS and IAS. The patient’s mental status does not seem to affect the result of this clinical test.

Proctography During dynamic proctography, anorectal anatomy and pelvic floor motion are recorded at rest, coughing, squeezing, and straining to expel barium from the rectum. Additionally, the anorectal angle and position of the anorectal junction are tracked during these maneuvers as well as retention and evacuation of contrast material. This test may be used to assess the presence of excessive perineal descent, a rectocele or enterocele, or internal rectal intussusceptions. This technique is rapidly being replaced by dynamic MRI because the technique for conducting MRI and interpretation of data are more standardized. Patients must be able to follow the commands for completion of this test.

Pelvic MRI This modality allows visualization of the anal sphincter anatomy and global pelvic floor motion in real time. Dynamic imaging of the pelvic floor is done as a patient squeezes the sphincter muscles to evacuate ultrasound gel from the rectum or perform the Valsalva’s maneuver. Examination may be performed in a supine or seated position. The latter technique is superior to EAUS for detecting rectal intussusceptions. Endoanal MRI has been shown to be equal or superior to EAUS for assessing the EAS. It also allows detection of PBR atrophy in FI. Added benefits include dynamic assessment of global pelvic floor motion and visualization of the bladder and genital organs.

Needle electromyography of the external sphincter The EAS and PBR muscles are assessed by needle insertions and measurement of insertional activity at rest, motor unit potential amplitude and duration, percentage of polyphasia, and recruitment following mild to moderate voluntary contraction. EAUS, however, has largely replaced it for identifying sphincter defects.