Fecal incontinence in the elderly

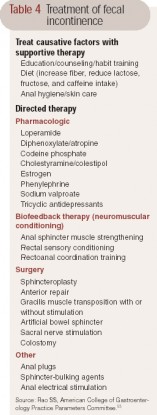

Diarrhea and constipation are independent risk factors for fecal incontinence. Therefore, medical management of FI is directed toward identifying and treating the underlying disorders causing diarrhea or constipation (see Table 4). Surgical and behavioral treatments address the integrity and strength of the pelvic floor muscles as well as sensory dysfunction of the rectum associated with neurologic and anatomic defects. When both treatment modalities fail to restore bowel control or improve quality of life, therapy is targeted toward providing symptom relief.

Medical management Supportive treatment should begin with simple lifestyle modifications such as avoiding certain foods and bowel habit training. Treatment of underlying causes of diarrhea or constipation may result in cure in a small subset of patients. Avoiding caffeine, a gastrocolonic stimulant, after meals as well as brisk physical activity immediately postprandially may lessen urgency and diarrhea. In all patients, especially the institutionalized, good skin hygiene is important to prevent skin breakdown. Frequent cleansing, changing of undergarments, and use of barrier creams such as silver sulfadiazine, zinc oxide, and calamine lotion may prevent skin excoriation. Scheduled or ritualized toileting, instituting cognitive training, and providing easily accessible facilities such as bedside commodes and bedpans may prove helpful in decreasing frequency of soiling and accidents.

Table 4 Treatment of fecal incontinence

Table 4 Treatment of fecal incontinence

Bulking agents such as soluble fiber may be used to increase stool bulk, but there is little evidence to support this approach. Antidiarrheal agents such as loperamide are the first line of pharmacologic agents employed in persistent diarrhea. Loperamide, a synthetic opioid, decreases intestinal motility and secretion. A placebo-controlled trial of loperamide showed reduced frequency of incontinence, improved stool urgency, and increased colonic transit time as well as an increase in anal resting sphincter pressure and reduced stool weight. Loperamide taken before social occasions may help incontinent patients avoid accidents and thus encourage participation in social activities; however, common side effects include constipation and dependency.

Diphenoxylate/atropine is an alternative drug that is used with variable results. Codeine phosphate does provide benefit but at the potential cost of increased drowsiness and addiction. Cholestyramine/colestipol may be used in patients with ileal resection for whom bile salt malabsorption may be the underlying disorder. Other agents such as estrogen and sodium valproate have been tried with mixed results. Agents such as tricyclic antidepressants have been used empirically to improve symptoms for patients with idiopathic FI. In an open-label study of low-dose amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with idiopathic FI (mean age, 66 years), 89% of patients reported improvement in symptoms and reduced number of bowel movements per day (P*gt; .001). Phenylephrine gel has been shown to increase resting anal canal pressure and FI scores for patients with ileoanal reservoir pouch and FI.

In patients with constipation, fecal impaction, and overflow incontinence, regular colonic evacuation with enemas, digital stimulation with bisacodyl or glycerin suppositories, fiber supplementation, and selective use of oral laxatives may prove helpful.

Biofeedback Biofeedback is usually the first line of treatment if medical management fails. It is based on the principles of operant conditioning, and is used in cooperative patients with weak sphincters and/or impaired rectal sensation. Using a rectal balloon anal manometry device, patients are taught to contract the EAS when they perceive balloon distention. The goal is to improve contraction of the EAS in response to rectal distention, and visual, auditory, or verbal feedback techniques may be employed. Most patients seem to require 4 to 6 training sessions for a sustained response. Most studies revealed short-term subjective improvements of symptoms, but without improvement in objective anorectal measurements. Some studies do report improvement in voluntary squeeze pressure, rectoanal coordination, and rectal sensation and capacity. The evidence suggests that biofeedback has been found in the short term to improve symptoms and restore quality of life for patients aged 50 and older.

The presence of severe FI, pudendal neuropathy, and neurologic disorders portends a poor prognosis when treating with biofeedback. No reported randomized, controlled trials have compared biofeedback to other modalities including surgery. The technique remains incompletely standardized, and defining clinical improvement remains a challenge. However, given its safety profile and ease of application, biofeedback should be offered to all patients with intact cognitive function in whom supportive medical therapies have failed.

Anal plug devices, injectable sphincter-bulking agents (eg, autologous fat, collagen and implantable microballoons, carbon-coated beads and silicone), and electrical stimulation of the sacral nerve should be considered experimental therapies. Disposable anal plugs for temporary occlusion of the anal canal may be useful for patients with impaired anal canal sensation and neurologic disease and for institutionalized or immobilized patients. Short-term improvement has been shown with bulking of the anal sphincter to augment surface area and provide a tighter seal for the anal canal. The use of sacral nerve stimulation as an alternative treatment warrants further study.