Wound-healing role for microRNAs in colon offer new insight to inflammatory bowel diseases

A microRNA cluster believed to be important for suppressing colon cancer has been found to play a critical role in wound healing in the intestine, UT Southwestern cancer researchers have found.

The findings, first discovered in mice and later reproduced in human cells, could provide a fresh avenue for investigating chronic digestive diseases and for potentially repairing damage in these and other disease or injury settings.

“We identified a novel role for microRNAs in regulating wound healing in the intestine. This finding has important implications for diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease and may be relevant to wound healing mechanisms in other tissues,” said Dr. Joshua Mendell, CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research, Professor of Molecular Biology, and member of the UT Southwestern Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease - the two most common inflammatory bowel diseases affecting an estimated 1.5 million in the U.S. - stem from an abnormal immune response, which results in the body mistakenly attacking cells in the intestine. The resulting chronic injury to the colon also is considered a risk factor for colon cancer. Understanding the cellular pathways involved could eventually lead to potential therapeutic treatments.

MicroRNAs serve as brakes that help regulate how much of a protein is made, which, in turn, determines how cells respond to various stimuli. Approximately 500 to 1000 microRNAs are encoded in the genomes of mammals. Dr. Mendell’s laboratory studies how these tiny regulators work normally and how diseases such as cancer arise when they function in an abnormal manner.

These latest findings, which appear in the journal Cell, focus on two microRNAs: miR-143 and miR-145. While there is extensive literature implicating these microRNAs in colon cancer, little is known about their natural function in the colon. So Dr. Guanglu Shi, postdoctoral researcher in Molecular Biology, and other researchers began their five-year investigation by removing or “knocking out” the gene that produces these two microRNAs in mouse models.

Intestinal bowel disease facts

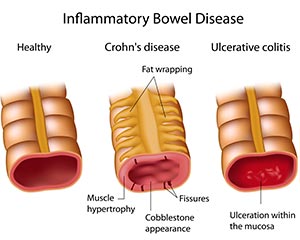

- The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The intestinal complications of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis differ because of the characteristically dissimilar behaviors of the intestinal inflammation in these two diseases.

- The intestinal complications of IBD are caused by intestinal inflammation that is severe, widespread, chronic, and/or extends beyond the inner lining (mucosa) of the intestines.

- While ulcerative colitis involves only the large intestine (colon), Crohn’s disease occurs throughout the gastrointestinal tract, although most commonly in the lower part of the small bowel (ileum).

- Intestinal ulceration and bleeding are complications of severe mucosal inflammation in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

- Intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease involves the entire thickness of the bowel wall, whereas the inflammation in ulcerative colitis is confined to the inner lining. Accordingly, complications such as intestinal strictures, fistulas, and fissures are far more common in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis.

- Intestinal strictures and fistulas do not always cause symptoms. Strictures, therefore, may not require treatment unless they cause significant intestinal blockage. Likewise, fistulas may not require treatment unless they cause significant abdominal pain, infection, external drainage, or bypass of intestinal segments.

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in Crohn’s disease can result from an intestinal stricture, is diagnosed by a hydrogen breath test, and is treated with antibiotics.

The researchers found that the cells that normally increase their growth to make repairs, called epithelial cells, fail under stress in the knockout animals. Epithelial cells line the intestines where food is digested, separating the contents from the rest of the body and absorbing needed nutrients.

The researchers found that the cells that normally increase their growth to make repairs, called epithelial cells, fail under stress in the knockout animals. Epithelial cells line the intestines where food is digested, separating the contents from the rest of the body and absorbing needed nutrients.

“The epithelial cells of the colon normally proliferate quickly to fill in the wounds from an injury. Without these microRNAs, the epithelial cells are unable to switch into this repair mode, so they never heal the wounds and the mice are not able to survive,” Dr. Shi said.

In addition, the research upended traditional thinking about where the tiny microRNAs reside, discovering to everyone’s surprise that they reside in supporting cells, called mesenchymal cells, instead of the epithelial cells themselves as previously thought.

“This was surprising because colon cancers derive from the epithelial cells, so it was assumed that the microRNAs must function within them,” Dr. Mendell said. “If these microRNAs do participate in colon cancer, they must do so by acting from outside the epithelium.”

Identifying the accurate location of the microRNAs is essential to locating the pathways they regulate and eventually, to determining whether they can be manipulated for therapeutic purposes.

Dr. Mendell’s team collaborated with a group of surgeons at UT Southwestern including Dr. Joselin Anandam, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Dr. Abier Abdelnaby, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Dr. Glen Balch, Assistant Professor of Surgery, and Dr. John Mansour, Assistant Professor of Surgery, and Dr. Adam Yopp, Assistant Professor of Surgery, who provided human tissue specimens. “The ability to work closely with an outstanding clinical team enabled us to confirm that our findings in mice extend to humans,” Dr. Mendell said.

In addition, the researchers say they have worked out one of the many pathways regulated by these microRNAs, called the insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway.

What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the name of a group of disorders in which the intestines (small and large intestines or bowels) become inflamed (red and swollen). This inflammation causes symptoms such as:

Severe or chronic (almost all of the time) pain in the abdomen (belly)

Diarrhea - may be bloody

Unexplained weight loss

Loss of appetite

Bleeding from the rectum

Joint pain

Skin problems

Fever

Symptoms can range from mild to severe. Also, symptoms can come and go, sometimes going away for months or even years at a time. When people with IBD start to have symptoms again, they are said to be having a relapse or flare-up. When they are not having symptoms, the disease is said to have gone into remission.

The most common forms of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UHL‑sur-uh-tiv koh-LEYE-tiss) and Crohn’s (krohnz) disease. The diseases are very similar. In fact, doctors sometimes have a hard time figuring out which type of IBD a person has. The main difference between the two diseases is the parts of the digestive tract they affect.

“This pathway is involved in many different processes in the body, but one function is to stimulate wound healing responses,” Dr. Mendell explained. “Increasing the amount of insulin-like growth factor signaling improves wound healing in the intestine.”

“This pathway is involved in many different processes in the body, but one function is to stimulate wound healing responses,” Dr. Mendell explained. “Increasing the amount of insulin-like growth factor signaling improves wound healing in the intestine.”

Knocking out miR-143 and miR-145 counteracts that effect.

Ulcerative colitis affects the top layer of the large intestine, next to where the stool is. The disease causes swelling and tiny open sores, or ulcers, to form on the surface of the lining. The ulcers can bleed and produce pus. In severe cases of ulcerative colitis, ulcers may weaken the intestinal wall so much that a hole develops. Then the contents of the large intestine, including bacteria, spill into the abdominal (belly) cavity or leak into the blood. This causes a serious infection and requires emergency surgery.

Crohn’s disease can affect all layers of the intestinal wall. Areas of the intestines most often affected are the last part of the small intestine, called the ileum, and the first part of the large intestine. But Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. Inflammation in Crohn’s disease often occurs in patches, with normal areas on either side of a diseased area.

###

Other researchers involved include Dr. Raghu Chivukula, a former M.D.-Ph.D. student at UT Southwestern.

UT Southwestern’s Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center is the only National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center in North Texas and one of just 66 NCI-designated cancer centers in the nation. It includes 13 major cancer care programs with a focus on treating the whole patient with innovative treatments, while fostering groundbreaking basic research that has the potential to improve patient care and prevention of cancer worldwide. In addition, the Center’s education and training programs support and develop the next generation of cancer researchers and clinicians.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution’s faculty includes many distinguished members, including six who have been awarded Nobel Prizes since 1985. Numbering more than 2,700, the faculty is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide medical care in 40 specialties to nearly 91,000 hospitalized patients and oversee more than 2 million outpatient visits a year.

###

Russell Rian

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

214-648-3404

UT Southwestern Medical Center