Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF- α) Inhibitors

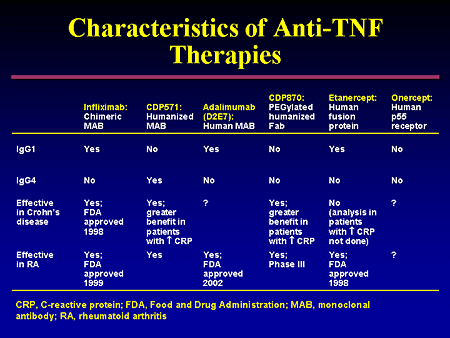

TNF- α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of IBD and has been found in increased concentrations in the mucosa and stool of patients with Crohn’s disease. There are currently three available anti- TNF monoclonal antibodies approved for use in Crohn’s disease. Infiiximab is a chimeric mouse-human IgG1 monoclonal antibody, whereas adalimumab is a humanized IgG1 antibody and certolizumab pegol is a pegylated Fab’ fragment.

All three TNF inhibitors bind with high specificity and affinity to soluble and membrane-bound TNF- α , leading to neutralization of its biological activity. Infiiximab and adalimumab, but not certolizumab pegol, also induce apoptosis of TNF expressing cells.

The first randomized controlled trial of infliximab in 1997 evaluated a single infusion in 108 patients with active Crohn’s disease and demonstrated clinical response at week 2 in 81 % of the infiiximab-treated patients versus 17 % of the placebo-treated patients. Subsequently, the ACCENT 1 trial evaluated the use of repeated infiiximab infusions for maintenance therapy in moderate-severe Crohn’s disease. In total, 58 % of patients responded within 2 weeks to the initial infusion of infiiximab, and those randomized to receive ongoing infusions achieved a 39 % remission rate at week 30, compared with 21 % of placebo-treated patients. When all patients treated with infiiximab were pooled, the odds ratio of sustained clinical remission with infiiximab compared to placebo was 2.7 and three times as many patients in the infiiximab group were able to discontinue steroids.

Interestingly, the real life experience with infiiximab seems to be even better than the clinical trials. In a Canadian cohort of 130 patients, most on concurrent immunomodulators, 83 % maintained clinical response at 30 weeks and 64 % at 54 weeks. Another study detailing a large single center experience with infiiximab showed an 82 % response to infiiximab induction, and a 66 % sustained clinical benefit.

Infiiximab has also proven effective for treatment of fistulas in Crohn’s disease. The initial study of its use for this indication included 94 patients with draining abdominal or perianal fistulas . Of the patients who received 5 mg/kg infiiximab induction dosing, 68 % had a reduction of at least 50 % in the number of draining fistulas, compared to 26 % of the placebo group, and 55 % of the patients in the infiiximab group had complete closure of their fistulas. Subsequently, the landmark ACCENT II trial demonstrated that continued infusions of infiiximab every 8 weeks was more effective than placebo in maintaining fistula closure. In this study 36 % of patients in the infiiximab arm had a complete absence of draining fistulas at week 54, a statistically significant increase from the placebo group. In this same trial, infiiximab was effective for inducing and maintaining closure of rectovaginal fistulas, and reducing the number of hospital days, surgeries, and procedures.

Infiiximab has also proven effective for treatment of fistulas in Crohn’s disease. The initial study of its use for this indication included 94 patients with draining abdominal or perianal fistulas . Of the patients who received 5 mg/kg infiiximab induction dosing, 68 % had a reduction of at least 50 % in the number of draining fistulas, compared to 26 % of the placebo group, and 55 % of the patients in the infiiximab group had complete closure of their fistulas. Subsequently, the landmark ACCENT II trial demonstrated that continued infusions of infiiximab every 8 weeks was more effective than placebo in maintaining fistula closure. In this study 36 % of patients in the infiiximab arm had a complete absence of draining fistulas at week 54, a statistically significant increase from the placebo group. In this same trial, infiiximab was effective for inducing and maintaining closure of rectovaginal fistulas, and reducing the number of hospital days, surgeries, and procedures.

Adalimumab has shown similar efficacy for induction of moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease, with 59 % of patients demonstrating response and 36 % achieving remission at 4 weeks . Among initial responders to induction therapy, more than one third were still in remission at 1 year with maintenance doses of adalimumab. Rates of response and remission were inversely correlated with duration of disease . A secondary analysis of patients with fistulizing disease showed a significant improvement in mean number of draining fistulas per day in the adalimumab group compared with placebo. At the end of 56 weeks, 33 % of patients on adalimumab had complete fistula healing versus (13 % placebo) and among these patients 90 % maintained fistula healing after an additional year of adalimumab. Adalimumab is also effective for patients with prior exposure to infiiximab who developed a secondary loss of response or intolerance. However, the response and remission rates are lower than in TNF-naпve patients.

The most recently approved TNF- α inhibitor used in the treatment of Crohn’s disease is certolizumab pegol, a pegylated humanized Fab’ fragment. Unlike infiiximab and adalimumab, certolizumab has not been shown to induce apoptosis of inflammatory cells. The initial study evaluating certolizumab showed, among patients with an elevated CRP, 37 % of patients had a clinical response at week 6, compared with 26 % in the placebo group. At week 26, there was no significant difference in rates of remission. In the PRECISE II study of certolizumab maintenance, 64 % of patients responded to induction therapy by 6 weeks . Among these initial responders, those who continued to receive certolizumab had a 48 % remission rate at week 26 versus 29 % of the placebo group. A sub- analysis showed that patients with a shorter disease duration (<1 year) at study entry had a significantly greater rate of clinical response and remission than those with longer disease duration. Certolizumab therapy was also associated with a significantly increased chance of perianal fistula closure in an open-label study and has been shown to be effective in patients who have experienced secondary failure of infiiximab.

Unfortunately, many patients who initially respond to anti-TNF therapy will eventually experience loss of response. One of the common and well-recognized mechanisms for attenuation of response is mediated by the development of anti-drug antibodies. These antibodies directed against the TNF antagonist molecule can result in drug-neutralization or accelerated clearance, leading to loss of clinical effectiveness. Strategies to prevent anti-drug antibody development include an induction dosing regimen, scheduled rather than episodic maintenance therapy, and co-administration of a thiopurine immunosuppressive or methotrexate.

Unfortunately, many patients who initially respond to anti-TNF therapy will eventually experience loss of response. One of the common and well-recognized mechanisms for attenuation of response is mediated by the development of anti-drug antibodies. These antibodies directed against the TNF antagonist molecule can result in drug-neutralization or accelerated clearance, leading to loss of clinical effectiveness. Strategies to prevent anti-drug antibody development include an induction dosing regimen, scheduled rather than episodic maintenance therapy, and co-administration of a thiopurine immunosuppressive or methotrexate.

If loss of response does occur, this can often be overcome by dose escalation or switch to another TNF antagonist and this management decision can be guided by monitoring of drug levels and anti-drug antibodies. Severe disease activity (as indicated by high CRP, high TNF levels, and low albumin) is also associated with accelerated clearance of TNF antagonists . This observation suggests that TNF antagonists should not be reserved for use only as a rescue therapy in the setting of severe disease, and when they are used in this setting higher doses may be required.

Potential adverse events associated with anti- TNF therapies include injection site or infusion reactions, neutropenia, demyelinating disease, hepatotoxicity, serious infections, congestive heart failure, rash and induction of autoimmunity. Worsening of demyelinating disorders has been described with anti-TNF agents and consequently it is recommended to avoid these medications in patients with a history of demyelinating neurologic disease. In general, TNF inhibitors should also be avoided in patients with advanced heart failure, as they have been associated with increased mortality in these patients. Approximately 50 % of patients receiving infiiximab develop antinuclear antibodies after 2 years, but drug-induced lupus is rare .

Paradoxical development of a psoriasiform rash has been described with TNF antagonists and often resolves with cessation of the anti-TNF agent. The risk of recurrence of psoriasis with a second TNF antagonist is about 50 % .

Serious infections occur in 2- 4 % of patients treated with anti-TNF therapy annually .

Patients and their providers should be aware of this risk and vigilant monitoring and early workup of infectious symptoms is advised.

Tuberculosis and Hepatitis B testing should be performed prior to initiating therapy, with initiation of treatment or vaccination for these infections as appropriate.

Lymphomas have been described in patients on TNF antagonists at rates higher than the general population. It is difficult to definitively attribute the lymphoma risk to TNF inhibitors alone, since most patients in whom this risk was studied were on concurrent or previous thiopurine therapy. Regardless, the absolute risk of lymphoma with a TNF antagonist and thiopurine in combination is low . Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma is a rare and particularly aggressive form of lymphoma that is seen primarily in young male patients with IBD on combination therapy with TNF antagonists and thiopurines . Consequently combination therapy should be carefully considered in this high risk group.

Lymphomas have been described in patients on TNF antagonists at rates higher than the general population. It is difficult to definitively attribute the lymphoma risk to TNF inhibitors alone, since most patients in whom this risk was studied were on concurrent or previous thiopurine therapy. Regardless, the absolute risk of lymphoma with a TNF antagonist and thiopurine in combination is low . Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma is a rare and particularly aggressive form of lymphoma that is seen primarily in young male patients with IBD on combination therapy with TNF antagonists and thiopurines . Consequently combination therapy should be carefully considered in this high risk group.

Patients on TNF inhibitors may also have a two to threefold increased risk of non- melanoma skin cancer, although studies have been mixed .

Additionally, there is likely a small increased risk of melanoma. Patients taking TNF inhibitor therapy should be advised on the importance of sun protection and regular skin exams. Despite the small increased risk of lymphomas and skin cancers, overall malignancy risk is not elevated in patients on TNF antagonist therapy.

###

R. A. Fausel , MD

T. L. Zisman , MD, MPH

Division of Gastroenterology, University of Washington Medical Center , 1959 NE Pacific Street, Box 356424 , Seattle , WA 98195 , USA

References

1. Sands BE, Siegel CA. Chapter 111: Crohn's disease. In: Sleisenger MH, Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. p. 1 online resource (2 volumes (xxv, 2299, xc pages)).2. Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions Jr JT, Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern Jr F, et al. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1979;77(4 Pt 2):847- 69.

3. Singleton JW, Hanauer SB, Gitnick GL, Peppercorn MA, Robinson MG, Wruble LD, et al. Mesalamine capsules for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: results of a 16-week trial. Pentasa Crohn's Disease Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1993; 104(5):1293- 301.

4. Hanauer SB, Stromberg U. Oral Pentasa in the treatment of active Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(5):379- 88.

5. Lim WC, Hanauer S. Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2010(12):CD008870.

6. Ford AC, Kane SV, Khan KJ, Achkar JP, Talley NJ, Marshall JK, et al. Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in Crohn's disease: systematic review and meta- analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):617- 29.

7. Box SA, Pullar T. Sulphasalazine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(3): 382- 6.

8. Navarro F, Hanauer SB. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: safety and tolerability issues. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(12 Suppl):S18- 23.

9. Muller AF, Stevens PE, McIntyre AS, Ellison H, Logan RF. Experience of 5-aminosalicylate nephrotoxicity in the United Kingdom. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(10):1217- 24.

10. Sutherland L, Singleton J, Sessions J, Hanauer S, Krawitt E, Rankin G, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of metronidazole in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1991;32(9):1071- 5.

11. Prantera C, Zannoni F, Scribano ML, Berto E, Andreoli A, Kohn A, et al. An antibiotic regimen for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: a randomized, controlled clinical trial of metronidazole plus ciprofioxacin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(2):328- 32.

12. Rutgeerts P, Hiele M, Geboes K, Peeters M, Penninckx F, Aerts R, et al. Controlled trial of metronidazole treatment for prevention of Crohn's recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(6):1617- 21.

13. Bernstein LH, Frank MS, Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Healing of perineal Crohn's disease with metronidazole. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(2):357- 65.

14. Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ, Frank MS. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(2):383- 7.

15. Thia KT, Mahadevan U, Feagan BG, Wong C, Cockeram A, Bitton A, et al. Ciprofioxacin or metronidazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(1):17- 24.

16. Dewint P, Hansen BE, Verhey E, Oldenburg B, Hommes DW, Pierik M, et al. Adalimumab combined with ciprofioxacin is superior to adalimumab monotherapy in perianal fistula closure in Crohn's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial (ADAFI). Gut. 2014;63(2):292- 9.

17. West RL, van der Woude CJ, Hansen BE, Felt- Bersma RJ, van Tilburg AJ, Drapers JA, et al. Clinical and endosonographic effect of ciprofioxacin on the treatment of perianal fistulae in Crohn's disease with infiiximab: a double-blind placebo- controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11- 12):1329- 36.

18. Jigaranu AO, Nedelciuc O, Blaj A, Badea M, Mihai C, Diculescu M, et al. Is rifaximin effective in maintaining remission in Crohn's disease? Dig Dis. 2014;32(4):378- 83.

19. Prantera C, Lochs H, Campieri M, Scribano ML, Sturniolo GC, Castiglione F, et al. Antibiotic treatment of Crohn's disease: results of a multicentre, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with rifaximin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(8):1117- 25.

20. Prantera C, Lochs H, Grimaldi M, Danese S, Scribano ML, Gionchetti P. Rifaximin-extended intestinal release induces remission in patients with moderately active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):473- 81.e4.

21. Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, Abreu MT, Abadir A, Marshall JK, et al. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):661- 73.

22. Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes JW, Goebell H, Ehms H, Sommer H, et al. European Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(2):249- 66.

23. Hayashi R, Wada H, Ito K, Adcock IM. Effects of glucocorticoids on gene transcription. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500(1- 3):51- 62.

24. Faubion Jr WA, Loftus Jr EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for infiammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(2):255- 60.

25. Benchimol EI, Seow CH, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Traditional corticosteroids for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2008(2):CD006792.

26. Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, Abreu MT, Marshall JK, Talley NJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):590- 9. quiz 600.

27. Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Price S, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn's disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1409- 22.

28. Curkovic I, Egbring M, Kullak-Ublick GA. Risks of infiammatory bowel disease treatment with glucocorticosteroids and aminosalicylates. Dig Dis. 2013;31(3- 4):368- 73.