Sterilization more common among rural women: study

Rural women, especially those without much education, are more likely to have their “tubes tied” in their 20s and early 30s than urban and suburban women, according to a new study.

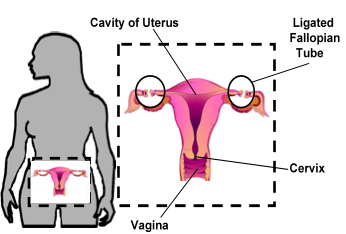

The procedure, known medically as tubal ligation, is a permanent form of birth control. Although it may be a good option for many women, researchers said, some others go on to regret it - especially when it’s performed at a young age.

It’s possible, they speculated, that more rural women get sterilized because they don’t have access to or can’t afford long-term but reversible forms of contraception, such as intrauterine devices.

“Long-acting reversible contraception is something we’d want these younger women (who get sterilized) to consider,” said Dr. Nikki Zite, from the University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine in Knoxville, who has studied trends in female sterilization.

But, she added, doctors who provide those options may be easier to find in cities.

For their new study, Dr. Britt Lunde from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and her colleagues analyzed data from a national survey of about 4,700 women aged 20 to 34, conducted in 2006 through 2010.

All of those women were sexually active without fertility problems, but did not want to become pregnant.

All of those women were sexually active without fertility problems, but did not want to become pregnant.

About 23 percent of women living in rural areas of the U.S. said they’d been sterilized. That compared to less than 13 percent of urban and suburban women.

The researchers found that disparity was especially strong among less educated women. More than 55 percent of rural women who hadn’t finished high school had been sterilized, compared to 26 percent of urban women without a high school degree.

However, a similar proportion of rural and urban women with more than a high school education reported tubal ligation - between seven and nine percent.

General geographic differences held up when the researchers accounted for women’s age and race, whether they were married and how many kids they had.

Making less money and not having private insurance were also tied to a higher likelihood of sterilization, they reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Making less money and not having private insurance were also tied to a higher likelihood of sterilization, they reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“From a study like this, we can’t always get the why,” Zite, who wasn’t involved in the new research, told Reuters Health.

“If they are women who genuinely understood they were being sterilized and desired sterilization, then I wouldn’t have a concern,” she said of rural women in the study.

But it’s unclear whether that was always the case. On the surveys, 39 percent of rural women and 37 percent of urban women who had been sterilized said they regretted the decision.

Many states extend Medicaid, the government-funded health insurance program for the poor, to pregnant women who might not otherwise qualify. Those women are then covered until two months after they give birth.

Some new mothers who have not been able to afford contraception may try to fit a tubal ligation into that post-delivery window so as not to worry about the cost of the procedure in the future, Zite noted.

She said going forward, the goal is to make sure women understand - and have access to - all contraceptive options.

“Health care providers and the public health system need to work to ensure equal and adequate access to all methods of contraception for all women, no matter their geographic location or education level,” Lunde and her colleagues wrote.

SOURCE: Obstetrics & Gynecology, online July 8, 2013.