A new study, published today in the journal Scientific Reports, has identified a rural community in Brazil that still follows the earlier sleep and wake times similar to pre-industrial times.

The team of researchers from the University of Surrey and the University of São Paulo studied the population of Baependi, a small rural town in south-eastern Brazil, whose sleep/wake cycle is much more aligned with that of our ancestors.

“In big cities, the availability of cheap electricity has brought us both artificial lighting and a multitude of other electronic devices that compete with us going to sleep at night,” said lead author Dr Malcolm von Schantz from the University of Surrey.

“As a result, most of us go to bed much later than our ancestors did, and, many of us are sleeping less. Even though the people in Baependi have access to electricity and television, their daily rhythms are much closer to those of previous generations. Studying this population is like being able to look back at past generations through a pair of binoculars and provide an insight into the benefit this natural pattern may be having on their health.”

As part of the study, people were asked when they would prefer to wake up and go to bed if they were completely free to plan their day. The average answers from town residents were 07.15 and 22.20, whereas people in the surrounding countryside preferred to rise at 06.30 and go to bed at 21.20. The researchers believe that the difference is due to town residents following much less of a natural sleep/wake cycle because of the influence of artificial lighting.

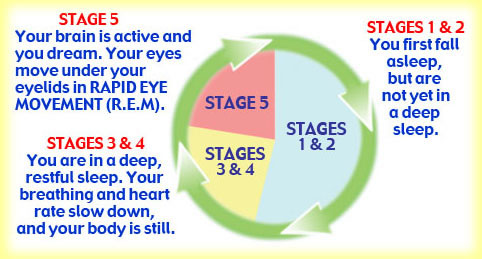

Our bodies require sleep in order to maintain proper function and health. In fact, we are programmed to sleep each night as a means of restoring our bodies and minds. Two interacting systems—the internal biological clock and the sleep-wake homeostat—largely determine the timing of our transitions from wakefulness to sleep and vice versa. These two factors also explain why, under normal conditions, we typically stay awake during the day and sleep at night. But what exactly happens when we drift off to sleep?

Prior to the era of modern sleep research in the early 1920s, scientists regarded sleep as an inactive brain state. It was generally accepted that as night fell and sensory inputs from the environment diminished, so too did brain function. In essence, scientists thought that the brain simply shut down during sleep, only to restart again when morning came.

EEGs are used in sleep studies to monitor brain activity during various stages of sleep.

EEGs are used in sleep studies to monitor brain activity during various stages of sleep.

In 1929, an invention that enabled scientists to record brain activity challenged this way of thinking. From recordings known as electroencephalograms (EEGs), researchers could see that sleep was a dynamic behavior, one in which the brain was highly active at times, and not turned off at all. Over time, sleep studies using EEGs and other instruments that measured eye movements and muscle activity would reveal two main types of sleep. These were defined by characteristic electrical patterns in a sleeping person’s brain, as well as the presence or absence of eye movements.

“When we asked the same question in London, the average answers were 08.30 and 23.15,” said Dr von Schantz.

“The people of Baependi, particularly those in the countryside, maintain a much stronger link with the solar rhythm, largely because many of them work outdoors. Midnight really represents the middle of the dark phase, and yet many of us in the industrialised world are not even in bed by then.

“Our colleagues at the University of São Paulo have studied this population, so there is a lot of data emerging about the health outcomes of the same population. We are optimistic that this project will teach us to what extent cardiovascular health, obesity, diabetes, and mental health problems may be associated with our move away from the natural day/night cycle, and the associated sleep loss.”

###

Amy Sutton

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

44-148-368-6141

University of Surrey

Journal

Scientific Reports