As many as one in 68 U.S. kids may have autism: CDC

As many as one in 68 U.S. children have autism, a 30 percent increase in just two years, U.S. health officials said on Thursday, but experts think the rise may simply reflect that parents and doctors are getting better at recognizing and diagnosing the disorder.

Experts were largely unfazed by the latest numbers, which they say do not necessarily suggest increasing prevalence.

“It’s not that surprising because as people get more aware, the prevalence has always increased in a psychiatric disorder,” Dr Thomas Frazier, director of Cleveland Clinic Children’s Center for Autism, said in a telephone interview.

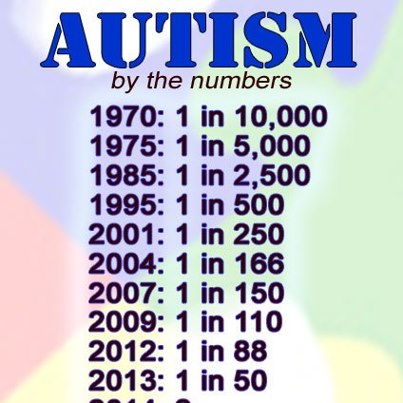

The latest report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which looks at data from 2010, estimates that 14.7 per 1,000 8-year-olds in 11 U.S. communities have autism. That compares with the prior estimate of 1 in 88 children, or 11.3 of 1,000 8-year-olds, in 2008, and 1 in 150 children in 2000.

Autism encompasses a spectrum of disorders, ranging from a profound inability to communicate and mental retardation to relatively mild symptoms in people with very high intellectual ability.

Coleen Boyle, director of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said while the report does not explain why rates are rising, it does give some clues.

For example, almost half of children identified as having autism in the latest report had average or above-average IQ levels, compared with just a third of children a decade ago.

For example, almost half of children identified as having autism in the latest report had average or above-average IQ levels, compared with just a third of children a decade ago.

“It could be doctors are getting better at identifying these children; it could be there is a growing number of children with autism at higher intellectual ability, or it may be a combination of better recognition and increased prevalence,” Boyle said.

Frazier said it is very likely that the current report is still undercounting autism rates among higher-functioning black and Hispanic children. Among black children with autism in the report, half also had intellectual disability, a more overt sign of problems. That compared with just 35 percent of white kids with autism, who also had intellectual disability.

Ultimately, Frazier thinks the autism rate will settle at around 2 percent of the population, or around 1 in 50 kids.

Part of the issue may be the way the CDC measures autism, combing through health and school records of 8-year-olds within fewer than a dozen communities in the United States.

The study showed significantly different autism rates by region, ranging from 1 in 175 children in Alabama to 1 in 45 children in New Jersey, which could reflect access to healthcare and other factors.

The CDC said the latest data continues to show that autism is almost five times more common among boys than girls, affecting 1 in 42 boys versus 1 in 189 girls.

White children are more likely to be identified as having autism spectrum disorder than are black or Hispanic children.

White children are more likely to be identified as having autism spectrum disorder than are black or Hispanic children.

The CDC only funded 12 tracking sites for the current study and data from only 11 were included in the report, a drop from 14 sites in the report issued two years ago, a reflection of tight budgets at the CDC that forced the agency to scale back.

And while the data cannot be generalized to a national population, Boyle said it is the best estimate available. “It’s not a national probability sample, but it is a very robust estimate and it’s the best we have.”

Rob Ring, chief science officer for the advocacy group Autism Speaks, said he does not think many autism researchers were surprised to see this increase.

He said the CDC’s method relies on individuals already flagged by the healthcare and education systems. “If you are not in those systems, you would not be counted.”

His group backed a 2011 study using a new research approach that found one out of every 38 children in South Korea may have autism.

The researchers used a painstaking research method that involved screening 55,000 children aged 7 to 12 in the South Korean city of Goyang. The team surveyed parents about their children’s behavior, then followed up with evaluations of at-risk children to confirm their diagnosis.

The population-based approach was designed to capture cases that might not be detected with methods that use school or medical records to identify autistic children.

Autism Speaks is partnering with the CDC to use this same research method in South Carolina, with results expected some time next year.

Dr Melissa Nishawala, medical director of the Autism Spectrum Disorders Clinical and Research Program at New York University’s School of Medicine, agrees that the new numbers likely reflect “the way we define autism and the way we look for cases and how good we are at finding cases.”

Nishawala said reports about high rates of autism are increasing awareness, and the latest numbers from the CDC will likely mean even more people look for signs in their children.

###

By Julie Steenhuysen