Parents’ ADHD goals tied to treatment choices: study

Parents’ goals and concerns for their children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder may influence their decision to start behavior therapy or medication, according to a new study that researchers say supports a shared decision-making approach to ADHD treatment.

Researchers found parents who were focused on their child’s academic achievement were twice as likely to have the child started on medications, which include Adderall and Ritalin, as other parents.

Parents who expressed goals of improved behavior and interpersonal relationships were 60 percent more likely to start behavior therapy - which involves parents meeting with a counselor to learn how to manage a child’s behavior.

“Studies like this really suggest that taking a shared decision-making approach may be one way to match the kids for whom (treatment) is warranted to the best treatment,” Dr. Alexander Fiks, from The Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said.

“For parents, the real thing is to ask pediatricians to really explain the pluses and minuses of all of the different options, and to make sure they can articulate what they’re really most hoping to achieve,” Fiks, the study’s lead author, told Reuters Health.

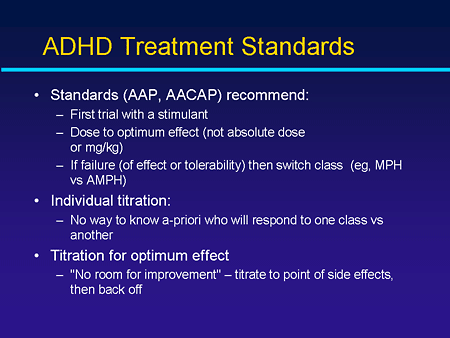

According to 2011 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics, “family preference is essential in determining the treatment plan” for children diagnosed with ADHD.

But Fiks said no one had looked at whether there were benefits to assessing parents’ preferences and goals for treatment.

But Fiks said no one had looked at whether there were benefits to assessing parents’ preferences and goals for treatment.

“There are barriers in real-world settings,” he noted. “It takes time, people are busy.”

For their study, Fiks and his colleagues surveyed the parents and guardians of 148 children with ADHD, ages six to 12, about their goals for treatment and the acceptability, feasibility and side effects they associated with different treatment options.

None of the children were using a combination of behavior therapy and medication at the outset, although some were using one or the other.

Six months later, 46 of the 108 children not initially using medication had started on the drugs and 30 out of 124 had started behavior therapy, according to findings published in Pediatrics.

Not surprisingly, researchers said, parents who had initially agreed with statements such as, “Medication is a reasonable way to help my child” and, “I would have trust in my doctor to treat my child’s ADHD with medicine” were more likely to go that route.

Likewise, children whose parents rated behavior therapy as more acceptable and said they would be comfortable working with a counselor were more likely to be receiving therapy six months later.

What was newer and more surprising, Fiks said, was how closely treatment goals aligned with which families opted for medication and which started behavior therapy.

Dr. Laurel Leslie, who has studied treatment of ADHD at the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, said those goals and subsequent choices are consistent with scientific evidence.

“What we do know is, a lot of the medications last under eight hours. So if you’re taking a medication, it’s probably only working during school time,” Leslie, who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Reuters Health.

Behavior therapy, on the other hand, is going to have the strongest effects with the family, at night and on weekends, she said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, parent reports suggest close to one in 10 kids and teens in the U.S. has ever been diagnosed with ADHD, and two-thirds of those with a current diagnosis are taking medication.

“I think this particular study speaks to the need to spend a little bit more time getting to know families … their own hopes and wishes for what is going to improve and preferences for how to go about making those benefits happen,” said Dr. Alice Charach, the head of neuropsychiatry at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Charach, who also wasn’t involved in the new research, recommended parents collect ideas and information before meeting with their child’s pediatrician.

“It’s helpful to have thought about what you hope to get out of the appointment and what your goals are for the child,” she told Reuters Health.

By the time children get to be nine or 10 years old, Charach added, they should be involved in the shared decision-making process as well.

###

SOURCE: Pediatrics, online September 2, 2013.