What, Exactly, Is Autism?

Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis (TSC), and Williams syndrome are rare conditions with clear genetic causes: Each springs from a mutation in a single gene - and with unusual frequency seems to simultaneously produce a more common condition: autism.

But is the “autism” in a child with Williams syndrome the same as in a child with fragile X? And how does it compare with autism of unknown causes?

“This is a really difficult question because - is it the same thing as what? We don’t have a model autism case,” said Bonita Klein-Tasman, PhD, professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “We have a pretty broad umbrella of what we consider to be autism right now.”

In terms of genetics, autism research is much more sophisticated than it was just a few years ago. Scientists have identified a few dozen genes that seem to be important players, and are hot on the trail of these genes’ malfeasance. But along with this increasing clarity, an existential crisis is emerging: What, exactly, is autism?

“Certain folks think that autism is a thing,” said Raphael Bernier, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington in Seattle. “I don’t think so. We’re defining it a certain way and there are a lot of different ways to get there.”

Social Subtlety

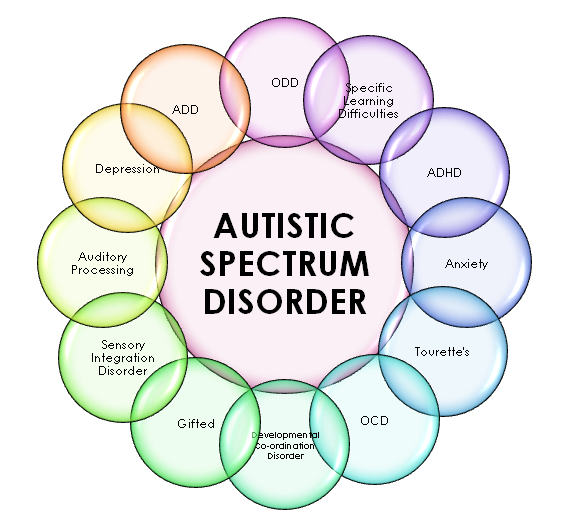

Some element of this uncertainty has always accompanied autism. Note the common saying: “If you’ve met one child with autism, you’ve met one child with autism” - a testament to the condition’s maddening diversity.

Some children with autism are social but awkward; others are socially withdrawn. Some don’t speak at all; others are hyperverbal. Some tune out all distractions and can focus intensely; others seem hyperactive and easily distracted.

Some children with autism are social but awkward; others are socially withdrawn. Some don’t speak at all; others are hyperverbal. Some tune out all distractions and can focus intensely; others seem hyperactive and easily distracted.

The advances in genetics over the past few years have only confirmed this variability. As researchers identify people with autism who share the same rare genetic mutation, they are finding that each subgroup has its own distinct profile, with differences even among members of the same subgroup.

“If we had good clinical data on 50 patients for each of the 500 or more predicted single-gene causes of autism, they’d probably all have a different profile,” said David Ledbetter, PhD, chief scientific officer at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania. “They’ll each have their own social communication and cognitive profile.”

Bernier brings children to his clinic from all over the world who bear rare mutations in any of a set of genes strongly linked to autism. Grouping these children by the mutation they carry, he paints portraits of their common features. For example, children with a mutation in CHD8 tend to have wide-set eyes, large heads, and trouble socializing. Many of them have what Bernier describes as “waiting-room autism” - meaning their autism can quickly be identified by sight alone: “I’m seeing a kid who is not engaged with others, who is not using broad facial expressions, not making eye contact.”

By contrast, children who carry a deletion in the 16p11.2 chromosomal region seem interested in socializing, but awkward, Bernier said. “Many of them have social quirks and oddities, but they’re not that waiting-room autism,” he says. “They are socially motivated and engaged but don’t know what to do once they are engaging with someone.”